A groundbreaking discovery by a team of bioarchaeologists from the Austrian Archaeological Institute at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Université de Bordeaux, and Aix-Marseille Université has shed light on an unexpected and fascinating practice in early modern France. In a paper published in the Scientific Reports journal, the team reveals the discovery of a family in France that embalmed their loved ones for nearly two centuries—something previously thought to be primarily a custom of Ancient Egypt and South American cultures. This discovery not only offers new insights into the history of embalming but also illuminates the cultural practices of an aristocratic family from the 16th to the 17th century, offering a rare glimpse into their lives and death rituals.

A New Chapter in Embalming History

While embalming has long been associated with Ancient Egypt, where it was used to preserve the bodies of the elite for the afterlife, the concept of preserving human remains has spread across different cultures and time periods. In many parts of South America, embalming was also practiced, with intricate techniques used to mummify important individuals. However, this new find challenges the geographical and cultural boundaries of embalming, extending the practice into the heart of Europe during the early modern period.

The team of researchers unearthed evidence of a fascinating embalming tradition practiced by the Caumont family, an aristocratic lineage from southwestern France. These findings offer not only a glimpse into the physical preservation of the dead but also into the cultural and societal values surrounding death, power, and legacy. What makes this discovery particularly remarkable is the longevity of the embalming tradition, which spanned across two centuries, from the early 1500s to the late 1600s. The fact that it was a multi-generational practice, passed down through time within the same family, provides valuable clues about the family’s wealth, influence, and social status.

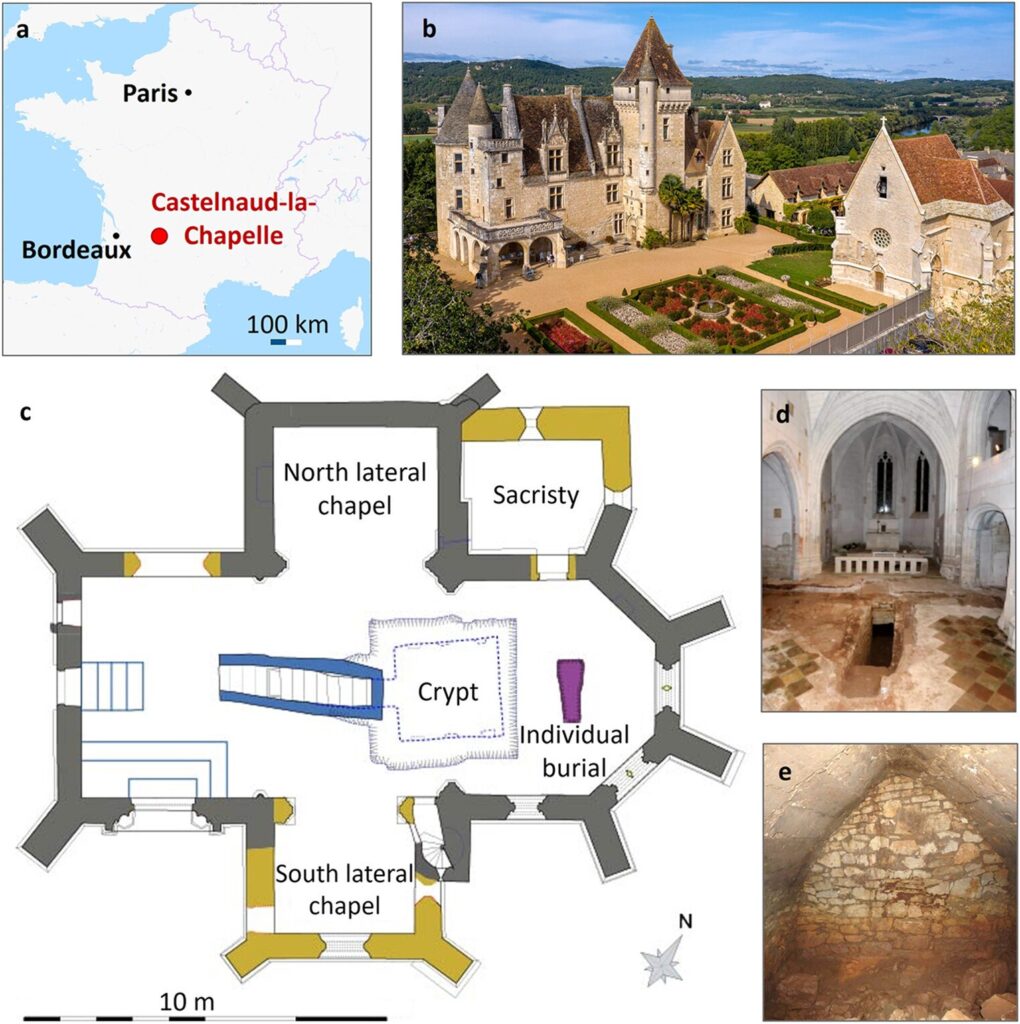

The Discovery at Château des Milandes

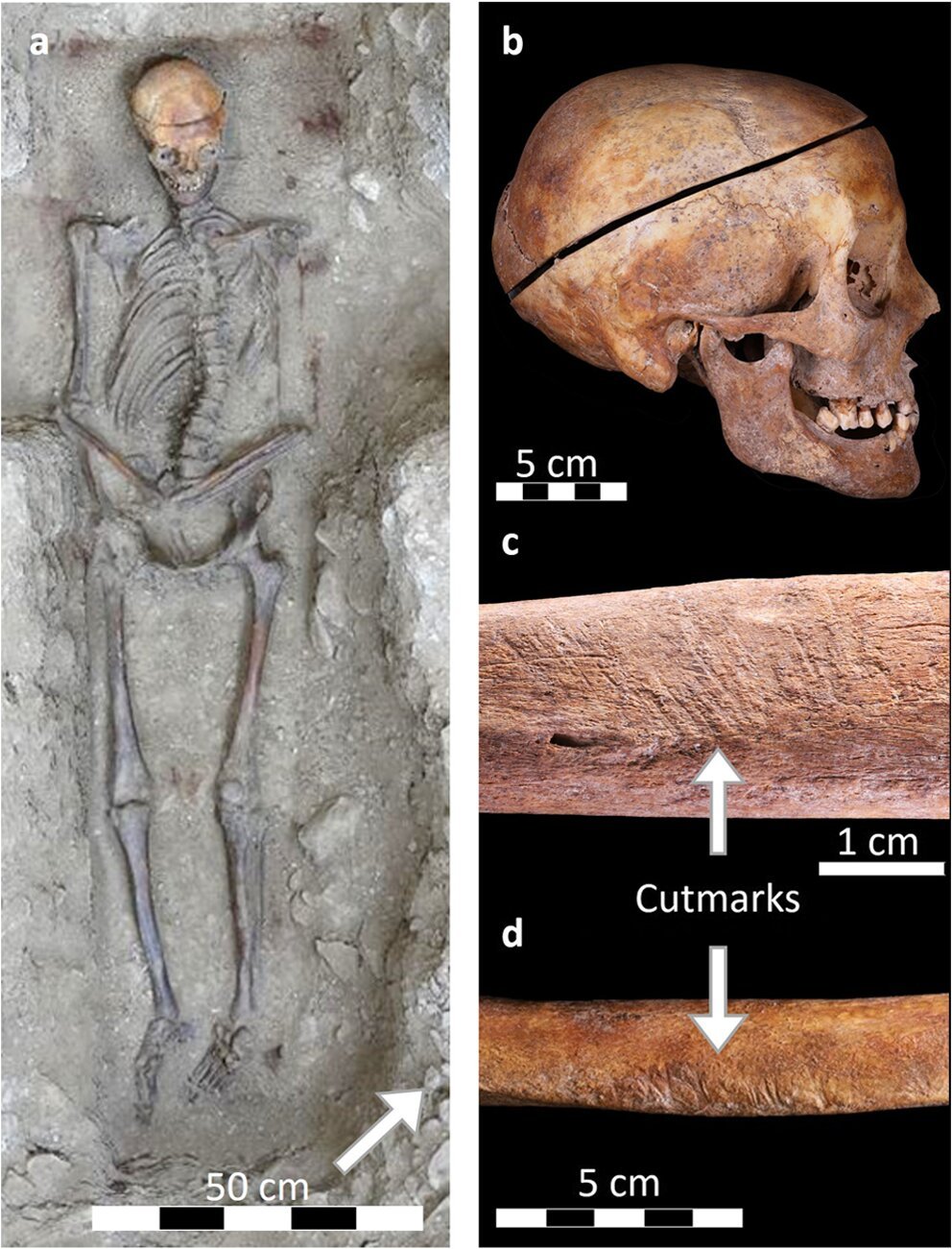

The research focused on the skeletal remains found in a crypt beneath the Château des Milandes, a grand estate historically tied to the Caumont family. Here, the researchers examined the remains of 12 individuals—seven adults and five children—interred together in the same crypt. This shared burial site became the focal point of an extraordinary discovery: not only were these people embalmed, but they all exhibited remarkably similar embalming techniques. The presence of approximately 2,000 bone fragments, all bearing evidence of embalming, offered the first tangible proof that such a practice was carried out across generations within the Caumont family.

As the team studied the remains, they discovered that the embalming process followed a remarkably consistent pattern. In each case, the body was carefully cleaned, and the internal organs—including the brain—were removed. The process was invasive, with skulls sliced open and the brain carefully extracted, a common practice among embalmers in other regions during this time. What followed was a meticulous procedure that involved the filling of the body with an embalming fluid made of balsam and other aromatic substances. These materials were intended to prevent decomposition long enough for the funeral rituals to be completed.

The team was able to confirm that the embalming process was not just a means of preservation for the elite but was rather a cultural and ceremonial necessity. It was not focused on preserving the body indefinitely, but instead, it served a more immediate and ritualistic purpose: ensuring that the deceased was adequately prepared for a proper burial ceremony. This distinguishes the French embalming practice from those of the ancient world, where preservation of the body for eternity was the central aim.

A Link to French Autopsy Manuals

One of the most striking aspects of this discovery is how the embalming techniques closely mirror descriptions in 18th-century medical texts, particularly those of French surgeon Pierre Dionis. Dionis, a prominent figure in the medical community, published an autopsy instruction manual in 1708, in which he detailed a method of embalming that bore striking similarities to the procedure used by the Caumont family. Dionis’s manual, which was widely circulated among medical professionals, described the process of removing internal organs, preparing embalming fluids, and carefully replacing the skull after the brain was removed—exactly as the researchers observed in the crypt.

This connection to Dionis’s manual offers strong evidence that the practice of embalming within the Caumont family was not just a spontaneous or isolated custom but was part of a broader, well-established tradition in France at the time. It suggests that the family’s embalmers were either directly influenced by or had access to medical knowledge that was already in circulation in the medical community of the era.

Embalming Children and Adults Alike

What further sets this discovery apart from other burial practices around the world is that the embalming procedure was applied equally to both adults and children in the Caumont family. While adult embalming was common in many aristocratic traditions, the practice of embalming children, especially over such a prolonged period, is a rare phenomenon. It’s possible that, for the Caumont family, the death of a child was viewed with the same significance and ceremonial importance as the death of an adult. This could indicate a strong cultural emphasis on preserving the family lineage and ensuring that even the youngest members of the family received the same rites as their elders.

The fact that the same embalming techniques were applied to all members of the family—regardless of age—suggests a uniformity in death rituals that highlights the importance of tradition and continuity for the Caumonts. This practice of embalming across generations may also suggest that the family, which likely held substantial social and political influence, wished to demonstrate their enduring legacy in both life and death. The physical preservation of their loved ones may have been a symbol of the family’s resilience and high social standing, further reinforcing their status in society.

Implications of the Find

The discovery of the Caumont family’s embalming tradition offers important insights into the social and cultural context of 16th and 17th-century France. The ritualized embalming of the dead suggests a family of considerable wealth, influence, and power, one that could afford the labor and materials necessary for such a procedure. Embalming, though not as widely practiced in Europe during this time as in Egypt or South America, was a symbol of aristocratic status and the desire to control the narrative surrounding death and legacy.

The fact that the family continued this practice for nearly two centuries is particularly remarkable. It suggests that embalming was not just a one-off or isolated tradition, but rather a deeply ingrained part of the Caumont family’s funeral customs. The long-term nature of this practice may also have allowed the family to reinforce their identity and continuity, using the embalmment of their loved ones to signify their place in history, perhaps even beyond death.

Moreover, this find opens the door for future research into similar practices across Europe. If other families or aristocratic houses followed comparable embalming traditions, it could drastically reshape our understanding of burial customs during the early modern period. The idea that embalming might have been a widespread but hidden practice among European elites invites further exploration into the intersection of death rituals, social status, and medical knowledge at the time.

Conclusion: A Rare Insight Into a Hidden Past

The discovery of the Caumont family’s embalming practices is an extraordinary finding that provides an intimate window into the rituals and traditions of early modern France. Through their research, the bioarchaeologists have uncovered not only the technical aspects of embalming but also the cultural and social values that shaped the way this aristocratic family approached death. The meticulous embalming of both adults and children over generations highlights the family’s wealth and status, while their adherence to a longstanding tradition suggests the importance of legacy and continuity in their society.

This discovery is a significant addition to the history of embalming, one that challenges our preconceived notions about the geography and practice of preserving the dead. It underscores the importance of interdisciplinary research in uncovering hidden aspects of history and offers a rare and fascinating glimpse into the death rituals of a family that, for nearly two centuries, sought to preserve not only their loved ones’ bodies but also their place in the annals of history.