When we think of “cold,” we might imagine a winter’s night, a snow-covered mountain, or perhaps the icy reaches of Antarctica. But these earthly chills are positively balmy compared to the extreme cold found in the vast expanse of the universe. Out there, in the deep, dark reaches of space, temperatures can plummet to levels we can barely comprehend. This is a world where atoms nearly stop moving, where energy is a precious commodity, and where the cold isn’t just an inconvenience—it’s a fundamental, all-consuming force.

This isn’t just about numbers on a thermometer. It’s about places so cold they defy our imagination, where the very rules of physics start to bend. Scientists have long sought out these cosmic iceboxes, not just for the thrill of discovery, but because in these freezing realms lie the secrets of the universe itself. So, grab your warmest coat and step with me into the coldest places in the universe.

The Concept of Cold: Absolute Zero and Beyond

Before we embark on our icy journey, we need to understand what we mean by “cold.” On Earth, we talk about freezing at 0°C (32°F) or bitter Arctic winds that drop temperatures to -50°C. But in physics, cold is more than just an uncomfortable experience—it’s a measure of how much energy atoms and molecules have.

Temperature is essentially a measure of the motion of particles. When something is hot, its atoms are vibrating and moving rapidly. When something is cold, they slow down. The coldest possible temperature is called absolute zero, which sits at 0 Kelvin (K), or -273.15°C (-459.67°F). At this temperature, atoms stop moving almost entirely. Scientists once thought absolute zero was a hard limit—nothing could get colder. And while it’s true you can’t go below absolute zero (as it represents zero thermal motion), scientists can get extremely close.

With that in mind, let’s explore the places in the universe that come eerily close to this ultimate chill.

1. The Boomerang Nebula: Nature’s Coldest Spot

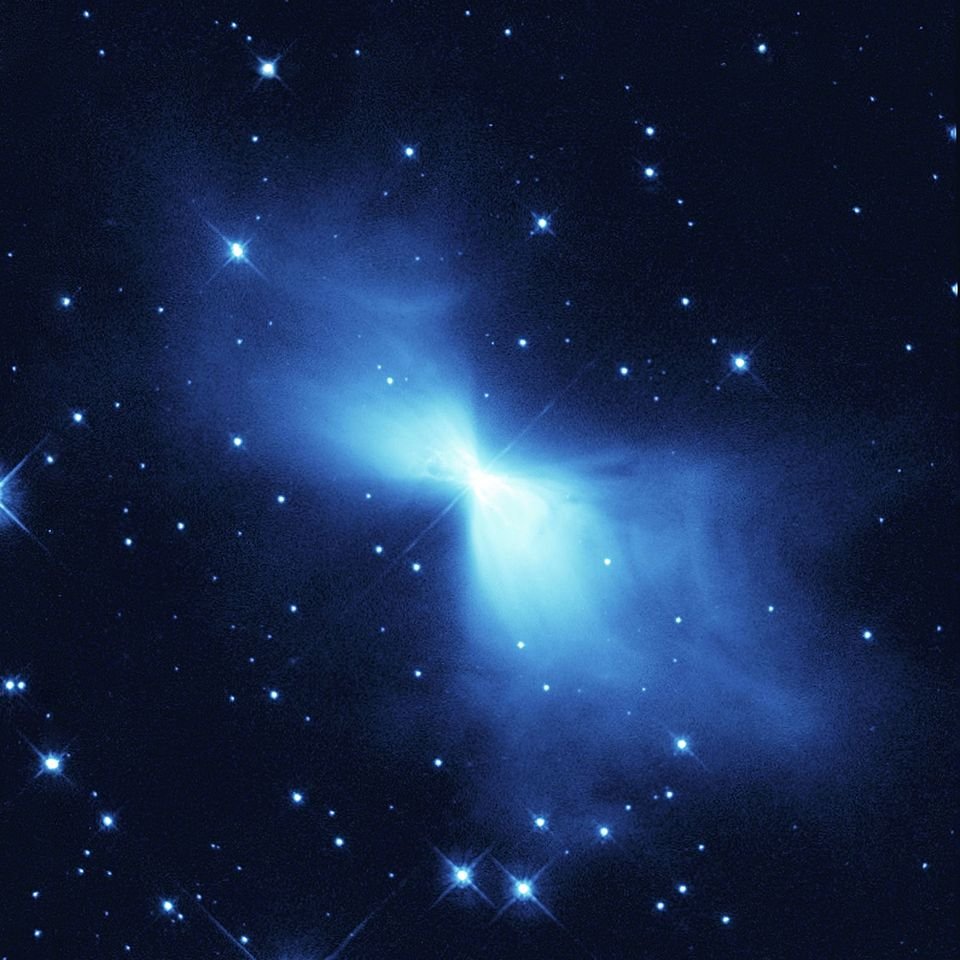

Our first destination is a bizarre and beautiful place called the Boomerang Nebula, floating 5,000 light-years away in the constellation Centaurus. To the eye, it’s a delicate cloud of gas and dust, stretching out into the cosmos like a ghostly butterfly. But behind its ethereal beauty lies something far more incredible: it is the coldest known natural place in the universe.

The Boomerang Nebula clocks in at a staggering 1 Kelvin, just 1 degree above absolute zero. That’s even colder than the empty space around it, which hovers at about 2.7 Kelvin, thanks to the lingering heat from the Big Bang known as the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation.

How does it get so cold? The Boomerang Nebula is a dying star, ejecting gas into space at breakneck speeds—about 600,000 kilometers per hour. As the gas expands, it cools rapidly. Imagine the way air from a spray can feels cold on your skin—that’s because it’s expanding and losing energy. Now scale that up to a cosmic level, and you have the Boomerang Nebula.

Astronomers first discovered the Boomerang in the 1980s and were shocked by its ultra-cold temperature. It challenges our understanding of how cold things can get in space naturally. In fact, it’s colder than the faint afterglow of the Big Bang that permeates the universe. If you could somehow stand inside the Boomerang Nebula (without dying from, well, everything), you’d be in the coldest natural environment we’ve ever found.

2. The Cosmic Microwave Background: The Big Chill of the Universe

Next, we turn our attention to something less localized but far more vast: the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMB). This is the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, the light that has been traveling across the universe for nearly 13.8 billion years.

As the universe expanded, this radiation cooled, and today it bathes the cosmos at a temperature of 2.725 Kelvin, just above absolute zero. That’s still unimaginably cold by human standards, but in the context of space, it’s considered the background warmth.

What’s fascinating about the CMB is that it’s remarkably uniform. Wherever you look in the sky, this microwave radiation is almost exactly the same temperature. Tiny fluctuations (mere millionths of a degree) are what led to the formation of galaxies and clusters of galaxies.

So, while it’s not the coldest specific place, the CMB is like an ever-present cosmic refrigerator, chilling the entire universe as it slowly, inexorably cools.

3. Dark Regions in Interstellar Space: Cosmic Deserts of Cold

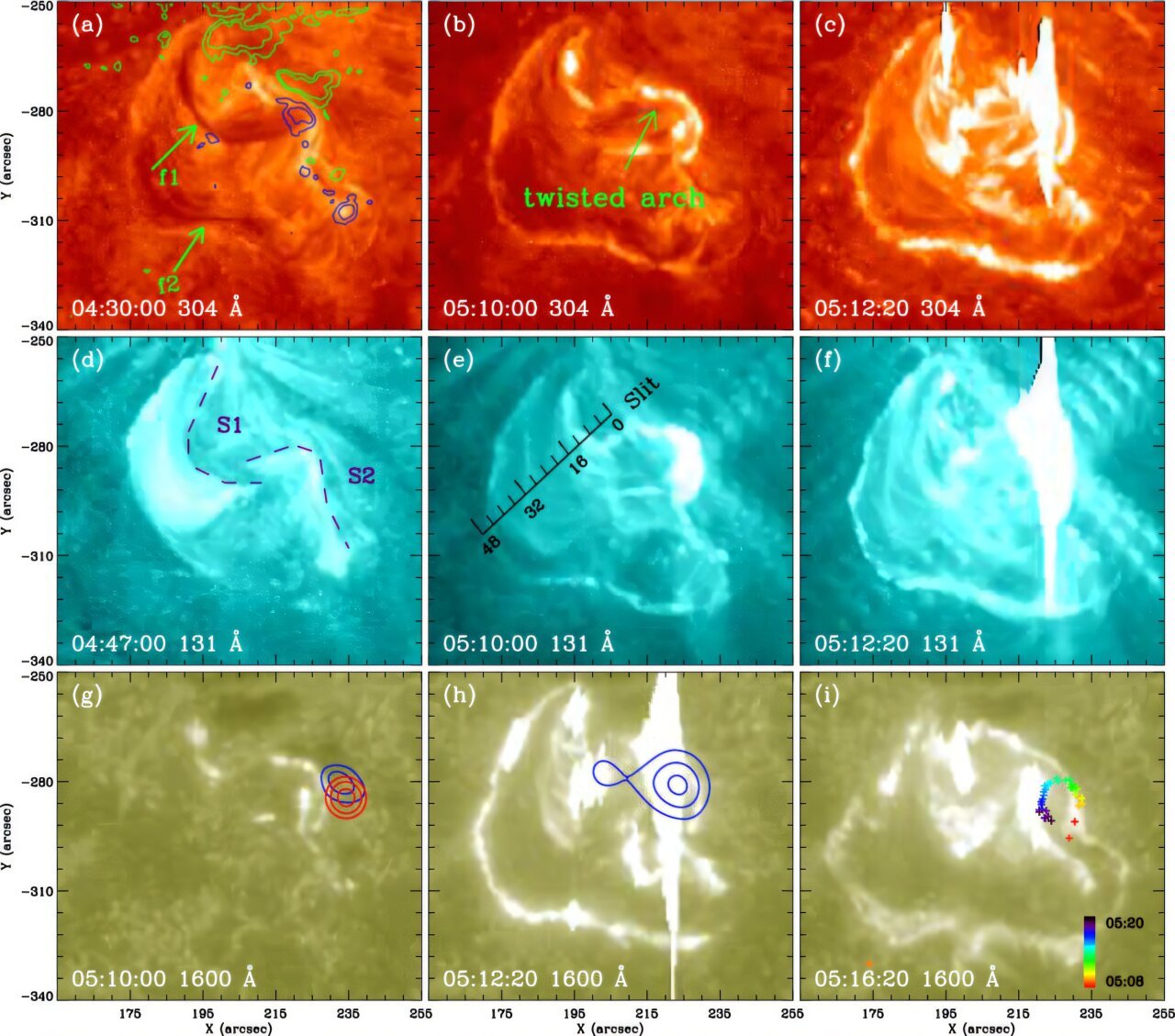

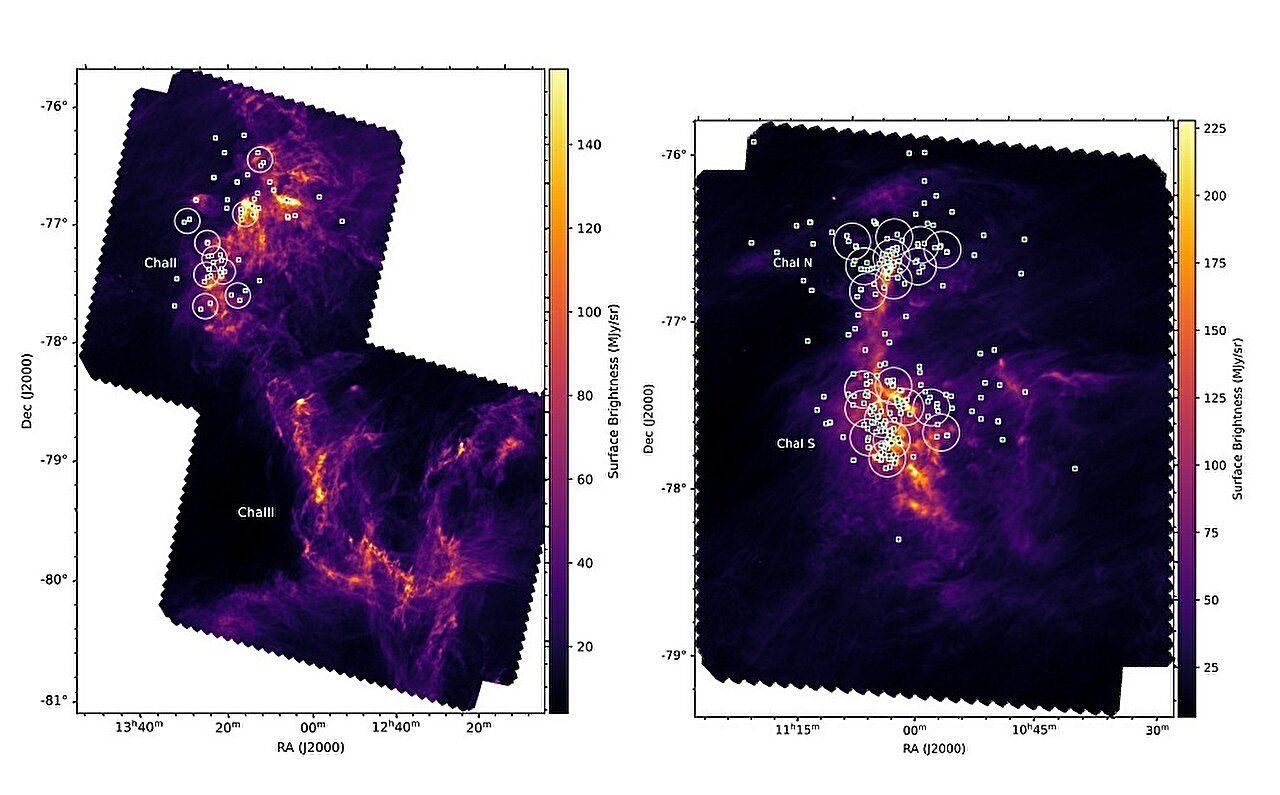

Between stars and galaxies lies the vast emptiness of interstellar space. These regions are often unimaginably empty, with just a few stray atoms floating in every cubic meter. But they’re also incredibly cold.

In the darkest, densest parts of these interstellar clouds, called molecular clouds, temperatures can drop to around 10 Kelvin. These cold regions are crucial to star formation. The frigid temperatures allow molecules to form and stick together, eventually collapsing under gravity to form new stars and planets.

Some of these regions, like the famous Horsehead Nebula in Orion, are visible through telescopes as dark patches blocking out the light of stars behind them. But their beauty belies a freezing heart—temperatures that could freeze nearly anything solid, including gases like oxygen and nitrogen.

4. The Coldest Artificial Place: The Laboratory Cold Beyond Space

So far, we’ve focused on naturally cold places. But what if we told you the coldest places ever aren’t out there in space but right here on Earth?

In laboratories, scientists have managed to create temperatures colder than anywhere else in the known universe. Using sophisticated equipment like laser cooling and magnetic traps, researchers have cooled atoms to a fraction of a billionth of a degree above absolute zero.

In 1995, scientists at the University of Colorado created a Bose-Einstein Condensate, a strange new state of matter, by cooling rubidium atoms to just 170 nanokelvin (that’s 0.00000017 Kelvin). In this state, the atoms behave like a single, unified entity—a “superatom.”

But the coldest record was set by scientists at the MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics, who cooled sodium-potassium molecules to just 500 nanokelvin, a mere half-billionth of a degree above absolute zero.

Even more astonishing, in 2018, NASA launched the Cold Atom Lab to the International Space Station, where they created conditions colder than any naturally occurring place in the universe, as low as 100 picokelvin (that’s 0.0000000001 Kelvin). In these cold labs, atoms practically stop moving, allowing scientists to study quantum phenomena in ways never before possible.

5. Neutron Stars and White Dwarfs: The Cold Hearts of Dead Stars

Neutron stars and white dwarfs are the remnants of stars that have ended their lives in supernova explosions. While you might expect them to be blisteringly hot (and they are, at first), over billions of years, they cool down, becoming dark and cold.

A neutron star is an object of almost unimaginable density—one teaspoon would weigh around a billion tons. Initially, neutron stars can be extremely hot, with surface temperatures of up to a million Kelvin. But after trillions of years (longer than the universe has existed so far), they’ll cool to near absolute zero, becoming what’s known as a black dwarf—a cold, dead remnant of a once-brilliant star.

As of now, we’ve never observed a black dwarf because the universe isn’t old enough for them to exist yet. But they are theoretical objects that represent the ultimate fate of many stars: cold, dark, and silent.

6. The Shadowed Craters of the Moon and Mercury: Cosmic Freezers Close to Home

You don’t have to venture across the galaxy to find extreme cold. Right here in our solar system, there are places where temperatures rival the deep reaches of space.

At the poles of the Moon and Mercury, there are craters that never see sunlight. These permanently shadowed regions are some of the coldest places in the solar system, reaching temperatures of 25 Kelvin (-248°C). That’s colder than Pluto!

These craters are cold traps for water ice and other volatile compounds, making them of particular interest for future space exploration. If astronauts can mine this ice, it could provide water, oxygen, and even rocket fuel.

7. The Expanding Universe and the Heat Death: The Ultimate Cold

If you want to talk about the coldest future, we need to look far ahead—trillions upon trillions of years into the future. As the universe continues to expand, stars will burn out, galaxies will drift apart, and the universe will become a dark, empty, and unimaginably cold place.

This is known as heat death, or the Big Freeze. Eventually, the temperature of the universe will drop so low that it will approach absolute zero. There will be no stars, no energy, and no life. Only black holes and the faint glow of Hawking radiation will remain—until they too disappear.

In this ultimate cold, the universe will be a vast, dark expanse where time itself loses meaning. It’s the coldest fate we can imagine for everything.

Conclusion: The Allure of Cosmic Cold

Why do we study these cold places? For one, they offer a glimpse into the extremes of nature. Cold reveals things we can’t see at higher temperatures—quantum phenomena, the birthplaces of stars, and the ultimate destiny of the universe itself.

But there’s also a strange beauty in the cold. In the Boomerang Nebula’s frozen shell, in the endless darkness of interstellar clouds, and in the unimaginable chill of the heat death, we find some of the universe’s most profound and poetic mysteries.

Cold, as it turns out, isn’t just the absence of heat—it’s a gateway to understanding existence at its most fundamental level. Whether it’s a laboratory on Earth creating conditions colder than space or the dying embers of a star slowly freezing in the night, these cold places teach us about where we came from, where we are, and where we’re going.

Epilogue: How Cold Is Cold?

| Location | Temperature |

|---|---|

| Absolute Zero | 0 K (-273.15°C) |

| Boomerang Nebula | 1 K (-272.15°C) |

| Cosmic Microwave Background | 2.7 K (-270.45°C) |

| Interstellar Molecular Clouds | 10 K (-263.15°C) |

| Lunar/ Mercury Shadowed Craters | 25 K (-248.15°C) |

| Laboratory Cold (Cold Atom Lab, NASA) | 100 picokelvin |

| Neutron Stars (Ancient, Black Dwarfs) | Near 0 K (theoretical) |

| Heat Death of the Universe | Near 0 K (theoretical) |