Imagine for a moment that you are standing alone in a dark, silent room. Suddenly, faint echoes begin to seep through the walls—whispers from a distant past, messages from a time long forgotten. Now, replace that room with the entire universe. The whispers you hear? They are photons—particles of light—that have been traveling for nearly 14 billion years. This ancient glow, faint yet omnipresent, fills every corner of the cosmos. It’s called the Cosmic Microwave Background, or CMB for short. It is, quite literally, the oldest light in the universe.

The CMB is more than just faint light. It is a relic, a living fossil, and a time capsule all at once. It carries within its faint glow the secrets of our universe’s earliest moments. It tells the story of how everything we know—galaxies, stars, planets, even life itself—came to be. Without it, we would be blind to our cosmic origins. With it, we can gaze into the depths of time and witness the universe as it was when it was just a baby.

This is the story of the CMB: what it is, how we found it, what it tells us, and why it’s one of the greatest discoveries in the history of science.

The Big Bang and the Birth of Light

What Happened at the Beginning?

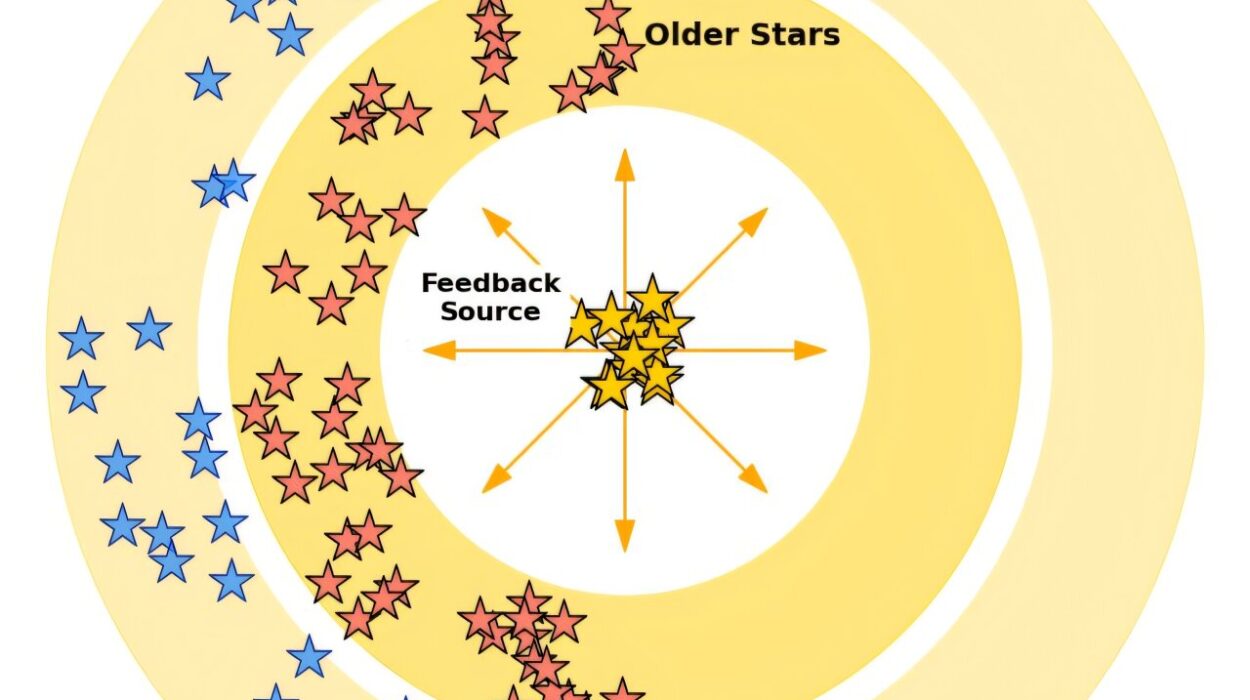

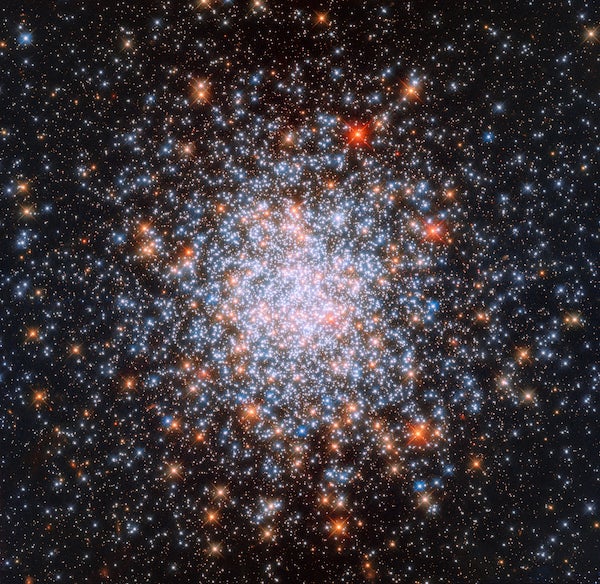

To understand the CMB, we have to start at the very beginning. The Big Bang wasn’t an explosion in space—it was the sudden expansion of space itself. Around 13.8 billion years ago, the universe was born in a hot, dense, and unimaginably small state. In its first fractions of a second, it expanded at a mind-boggling rate in what scientists call inflation. This sudden expansion smoothed out the universe but also left tiny fluctuations—quantum ripples—that would later seed the formation of galaxies.

In these early moments, the universe was a fiery soup of energy, light, and elementary particles. Protons, neutrons, and electrons collided violently in a thick, opaque plasma. Photons—the particles of light—were constantly scattered by free electrons. This meant the universe was a foggy, glowing cloud. Light could not travel freely. There were no stars, no galaxies, no atoms. It was hot, chaotic, and blinding.

But things were about to change.

Recombination: When Atoms First Formed

As the universe expanded, it cooled. After about 380,000 years, it reached a temperature of around 3000 Kelvin (about 2700°C or 4900°F). At this cooler temperature, electrons began to slow down enough to combine with protons, forming the first atoms—mainly hydrogen, the simplest element.

This event is called recombination, and it was revolutionary. Once electrons were bound into atoms, they no longer scattered photons. Light was finally free to travel unimpeded across the universe. The universe went from being an opaque fog to a transparent cosmic ocean.

The photons released at this moment are still traveling today. They have been stretched by the expansion of space, cooling and losing energy over billions of years. What was once bright visible light has shifted to microwave radiation, becoming the faint glow we now call the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Discovery by Accident—The Story of Penzias and Wilson

A Serendipitous Encounter With the Oldest Light

Fast forward to the 1960s. Physicists Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were working at Bell Labs in Holmdel, New Jersey. They were using a giant horn-shaped antenna to study radio waves. Their goal wasn’t to uncover cosmic secrets—they were troubleshooting a communication system.

But no matter how hard they tried, they couldn’t get rid of a mysterious background noise. They checked everything. They even cleaned out the pigeon droppings from inside the antenna! Yet, the hiss persisted. The noise was everywhere. It was the same in every direction, and it didn’t vary by season or time of day.

Unbeknownst to them, across town, a team of Princeton physicists led by Robert Dicke had been working on a theory predicting just such a signal. According to the Big Bang theory, if the universe began in a hot, dense state, there should be leftover radiation—cooled by the expanding universe—that we could still detect.

When Penzias and Wilson heard about this, they contacted the Princeton team. After analyzing the data, they realized they had stumbled upon the faint afterglow of the Big Bang—the Cosmic Microwave Background.

Penzias and Wilson published their findings in 1965. Though they hadn’t set out to detect the CMB, they had made one of the greatest accidental discoveries in history. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978.

Seeing the Universe’s Baby Picture

The First Images: COBE’s Groundbreaking Mission

For decades after its discovery, the CMB was known to be incredibly uniform. It was almost the same temperature—about 2.73 Kelvin, or just above absolute zero—everywhere in the sky. But scientists predicted there should be tiny fluctuations, little hot and cold spots, representing regions with slightly different densities. These variations would be the seeds that grew into galaxies and clusters of galaxies.

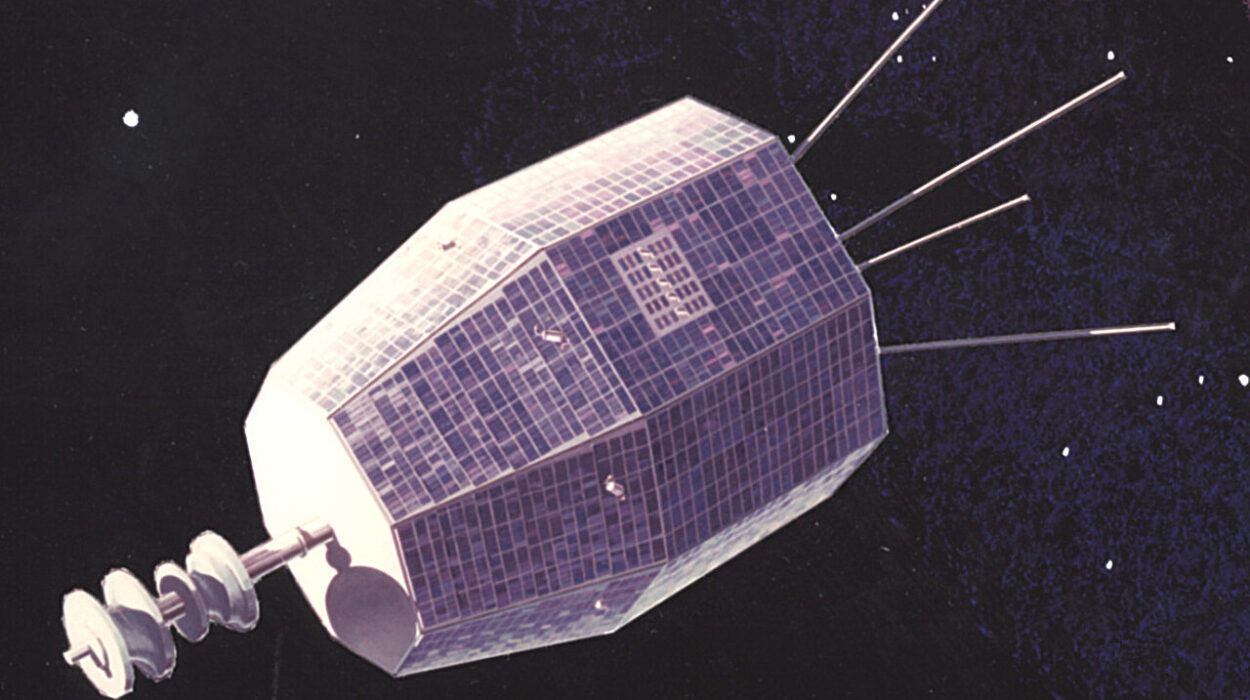

Enter COBE—the Cosmic Background Explorer, launched by NASA in 1989. COBE was designed to make precise measurements of the CMB’s temperature and look for these tiny differences.

In 1992, COBE delivered stunning results. It revealed slight variations in temperature—differences of just one part in 100,000. These tiny ripples were the fingerprints of the early universe’s structure. George Smoot, one of COBE’s scientists, famously described the discovery as “like looking at the face of God.”

COBE’s data confirmed the Big Bang model and showed how structure in the universe had begun to form. Smoot and his colleague John Mather were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2006 for their work on COBE.

Sharper Images: WMAP and Planck

COBE was just the beginning. In 2001, NASA launched the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). WMAP mapped the CMB with even greater resolution and sensitivity. It refined our understanding of the universe’s age, composition, and geometry.

WMAP told us the universe is about 13.8 billion years old, composed of 4.9% ordinary matter, 26.8% dark matter, and 68.3% dark energy. It also showed that the universe is remarkably flat, meaning its geometry follows the rules of Euclidean space.

Then came Planck, a European Space Agency mission launched in 2009. Planck produced the most detailed all-sky map of the CMB ever made. It revealed subtle anomalies, including a curious “cold spot,” that continue to intrigue cosmologists.

What the CMB Tells Us About the Universe

A Time Capsule From the Early Universe

The CMB is a cosmic Rosetta Stone, unlocking information about the early universe. Its temperature fluctuations tell us how matter was distributed when the universe was just 380,000 years old. These fluctuations grew into the vast cosmic structures we see today—galaxies, stars, and planets.

By studying the CMB, scientists can:

- Measure the universe’s age with incredible precision.

- Understand its composition, revealing the existence of dark matter and dark energy.

- Probe the physics of the early universe, including inflation, which explains the universe’s rapid expansion.

- Test theories of cosmology, including whether the universe is flat, open, or closed (spoiler alert: it’s flat).

Polarization: A New Layer of Information

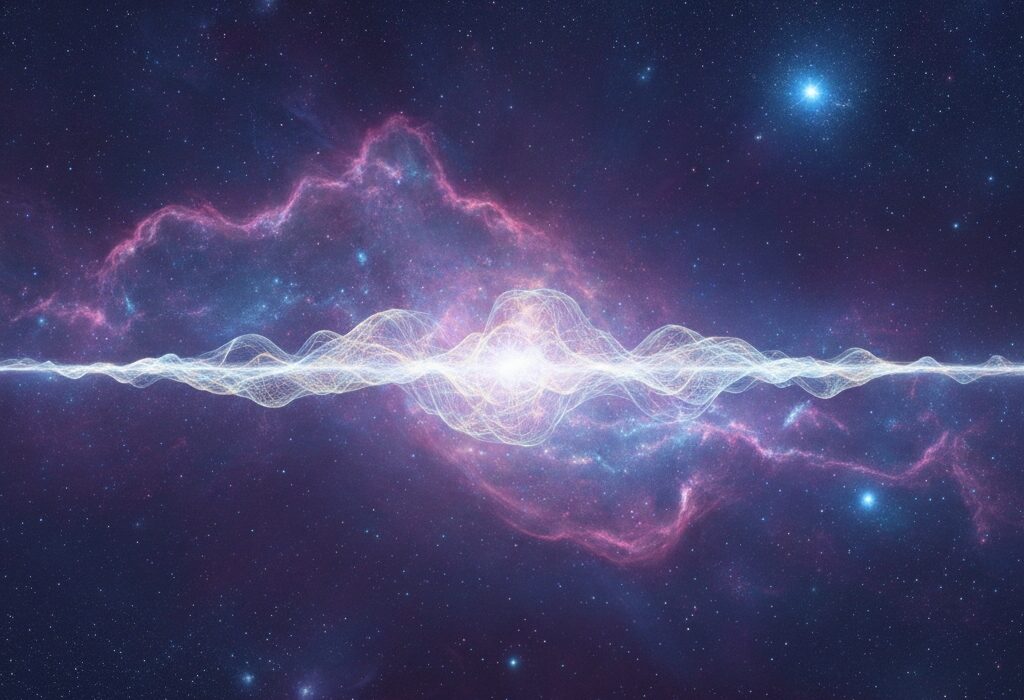

Beyond temperature, the CMB is also polarized. This polarization is caused by interactions between photons and electrons in the early universe. Studying polarization patterns provides insights into inflation and gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime caused by massive events.

In 2014, the BICEP2 experiment announced potential evidence of gravitational waves in the polarization of the CMB. While it turned out that galactic dust may have mimicked the signal, the search continues. Finding primordial gravitational waves would offer direct evidence for inflation and deepen our understanding of the universe’s birth.

Mysteries and Anomalies in the CMB

The Cold Spot: An Unsolved Puzzle

One of the most intriguing anomalies in the CMB is the so-called Cold Spot, a region significantly cooler than its surroundings. Discovered by WMAP and confirmed by Planck, the Cold Spot defies easy explanation.

Some theories suggest it’s the result of a supervoid—a vast region with fewer galaxies, causing light to lose energy as it passes through. Others propose exotic explanations, like interactions with other universes or defects in spacetime called topological defects.

The Axis of Evil?

Another puzzling feature is the apparent alignment of temperature fluctuations along a particular direction in space, whimsically dubbed the Axis of Evil. This alignment challenges the assumption that the universe should look the same in all directions—an idea known as cosmic isotropy.

Are these anomalies just statistical flukes, or signs of new physics? We don’t yet know. But they keep cosmologists awake at night.

The CMB in Popular Culture and Everyday Life

The Static on Your TV

Believe it or not, the CMB makes cameo appearances in your living room. If you ever tuned an old TV set to an unused channel and saw static, part of that hiss—roughly 1%—was CMB radiation. You were seeing ancient light from the birth of the universe.

Cosmic Echoes in Storytelling

The CMB has also captured the imagination of artists, writers, and filmmakers. It represents a connection to the universe’s origin and our place within it. In many ways, the CMB is a cosmic storyteller, whispering the tale of creation to anyone who will listen.

The Future of CMB Research

New Missions on the Horizon

Scientists aren’t done with the CMB. Upcoming missions like LiteBIRD and CMB-S4 aim to measure polarization with unprecedented precision. They hope to detect signs of primordial gravitational waves, shedding light on the inflationary epoch.

Beyond the CMB: New Cosmic Signals

While the CMB is the oldest light we can see, other cosmic messengers—like neutrinos and gravitational waves—offer new ways to study the early universe. Together, these signals form a multi-messenger approach to cosmology.

Conclusion: Listening to the Universe’s First Breath

The Cosmic Microwave Background is more than just faint radiation. It is the afterglow of creation itself, a fossil from the dawn of time. It tells us who we are and where we come from. It whispers the secrets of the universe to those who dare to listen.

In a sense, we are all children of the CMB. Every atom in your body was forged in stars, and those stars grew from the seeds planted in the fluctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background. When we study it, we are looking at our own cosmic heritage.

The next time you gaze up at the night sky, remember: the universe is still singing its first lullaby, and we are just beginning to understand the tune.