A recent and deeply revealing study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology has provided a haunting glimpse into the medical practices of the 19th century, particularly the use of mercury as a treatment for diseases that are now understood to be caused by simple nutritional deficiencies. The study, which examined the skeletal remains of a child from mid-19th-century France, revealed a heartbreaking tale of illness, medical experimentation, and premature death, all influenced by the social and scientific environment of the Industrial Revolution. The child, aged only 3 to 4 years old at the time of death, had suffered from both rickets and scurvy—two debilitating diseases linked to severe vitamin deficiencies—and was likely subjected to mercury treatment before succumbing to the toxic effects of the substance.

This study offers a window into the medical practices of the time and the dark paradox of mercury’s historical appeal. Despite being widely known today for its toxic properties, mercury was once considered a magical remedy for various diseases, ranging from venereal diseases to skin conditions. As researchers Alexandra Zinn and Dr. Antony Colombo explain, there is a stark contrast between mercury’s high toxicity, which is well-documented in modern science, and its perceived healing properties during the 19th century. To understand how such a treatment could have been considered both effective and necessary, we need to explore the medical, social, and economic context of that era.

The Context of Mercury in Historical Medicine

The use of mercury in medicine is far from a modern phenomenon. Its medicinal use dates back over 2,000 years, with references to its therapeutic applications found in the ancient medical texts of Greece, Egypt, China, and Arabia. In these civilizations, mercury was primarily employed to treat conditions such as skin diseases, venereal infections, and even digestive issues. Its use continued throughout the centuries, particularly during the medieval and Renaissance periods, when it was a cornerstone of alchemical and medical practices.

By the time the 18th century dawned, mercury had cemented its place as a widely accepted medical treatment, especially for venereal diseases like syphilis. However, it was during the Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 18th century and spread to France and other parts of Europe in the 19th century, that mercury’s use in medicine became more widespread. This period was marked by rapid advancements in both technology and medicine, which led to the development of new treatments, surgical practices, and public health policies. At the same time, however, industrialization also brought about environmental pollution, overcrowding, and poor living conditions for the working classes, which contributed to a rise in deficiency diseases like rickets and scurvy.

Rickets, Scurvy, and the Effects of Industrialization

Rickets and scurvy are diseases that are both caused by vitamin deficiencies—rickets results from a lack of vitamin D, while scurvy is due to a deficiency of vitamin C. In the 19th century, these diseases were especially prevalent among the lower socioeconomic classes, who had limited access to fresh foods, sunlight, and proper nutrition. The rapid industrialization in France and other countries contributed to these issues, as urbanization and factory work left children vulnerable to poor health conditions, malnutrition, and diseases like rickets and scurvy.

Scurvy, for example, was a common affliction during long periods when fresh fruits and vegetables were scarce, leading to widespread outbreaks in the lower classes. Rickets, similarly, was caused by a lack of sunlight and poor dietary habits, particularly among urban children who spent little time outdoors and were not provided with the necessary nutrients to ensure healthy bone development. These diseases were devastating, especially for children, and often led to permanent disability or death if left untreated.

As researchers Zinn and Colombo note, the impact of industrialization on child health in France was particularly pronounced. While industrialization in the UK had a more abrupt and wide-reaching impact, France’s industrialization took a slightly different path, coming later and being less dramatic. However, the social and political upheaval of the time, combined with economic disparities, created conditions where diseases like rickets and scurvy were rampant among children, particularly those in working-class families.

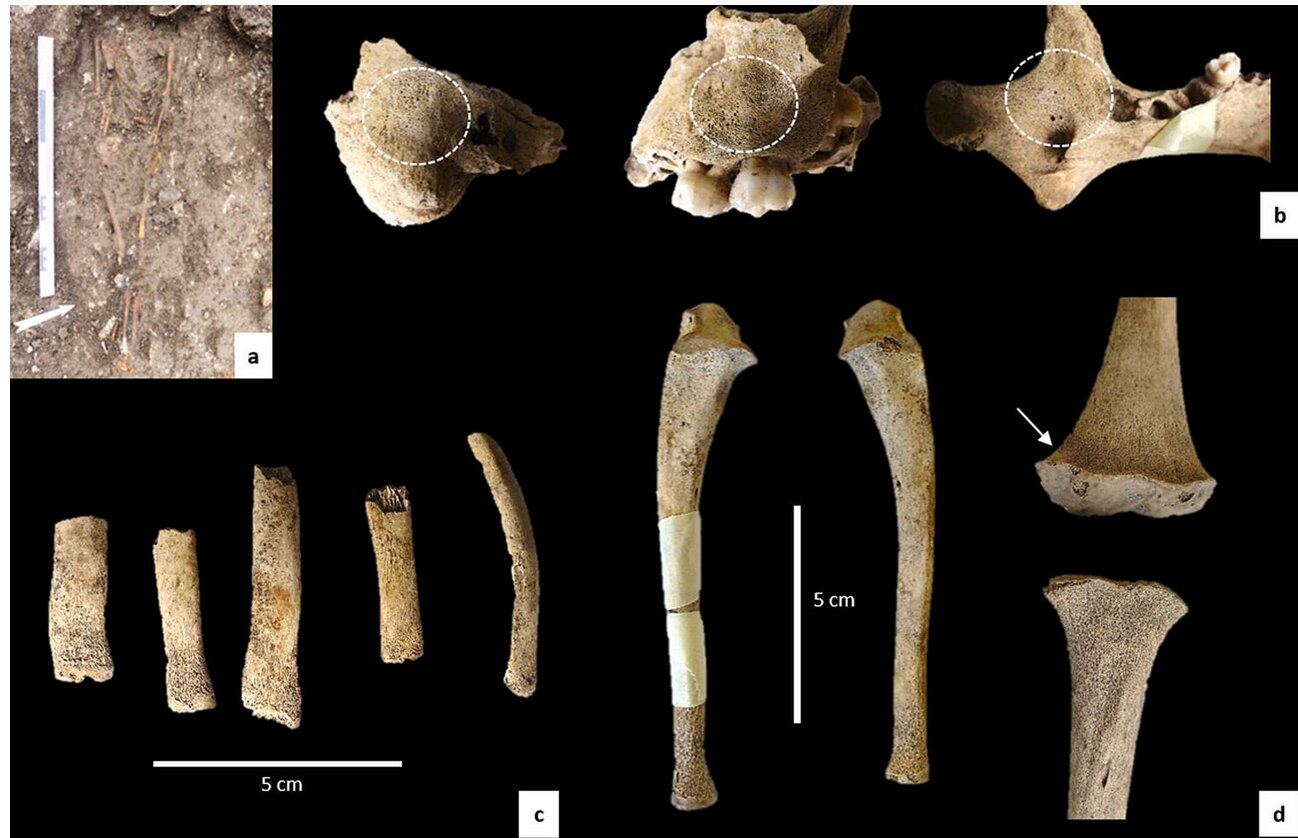

The Discovery of Mercury in the Child’s Bones

The skeletal remains of the child in question were discovered during archaeological excavations at the Rue Thubeuf site in Rouen, France, an area that was once home to a bustling community in the 18th and 19th centuries. The remains were part of a collection of 53 burials found at the Saint-Gervais parish cemetery, which spanned the period from the 18th to the 19th century. Among these burials, the remains of 18 individuals were studied in detail, including the child identified as SP5.

Using advanced techniques like micro-CT scanning, X-ray fluorescence, and cold vapor atomic absorption spectrometry—an extremely sensitive chemical detection method—the researchers were able to uncover startling findings. The child’s bones and teeth revealed clear signs of both rickets and scurvy, consistent with a severe lack of vitamin D and C. What was even more concerning, however, was the presence of unusually high levels of mercury in the child’s skeletal remains, particularly in the bones and teeth. The mercury levels were far beyond what would be expected from environmental contamination or exposure to pollutants.

At first, the researchers considered the possibility that the mercury could have been the result of contamination from the soil, the child’s occupation, or the local environment. However, they quickly ruled out these possibilities. The geology of Rouen, for example, does not contain mercury-rich minerals, and the area’s industrial activities, such as cotton textile production and gilding, did not involve the use of mercury in the same way that other industries, like those producing mirrors or hats, might have. Additionally, the fact that the child was so young made it unlikely that he would have been exposed to mercury through occupational means.

Given the timing of the mercury exposure and the child’s condition, the researchers concluded that the most likely source of the mercury was medical treatment. During the 19th century, mercury was commonly prescribed to treat various ailments, including skin diseases and venereal infections, and was even used to treat rickets and scurvy in some cases. This medical practice was based on the belief that mercury could “purge” the body of disease, despite the fact that it was highly toxic and caused severe side effects, including dizziness, tooth loss, and even death in extreme cases.

The Tragic Consequences of Mercury Treatment

Mercury treatments were not only ineffective but also extraordinarily dangerous. The substance was known to cause a range of toxic symptoms, including asphyxiation, delirium, excessive salivation, and inflammation of the tongue, a condition called “mercurial glossitis.” Patients undergoing mercury treatment were often subjected to painful and exhausting procedures, and the treatment was considered “successful” when excessive salivation appeared—an indication that the body was “expelling” the mercury. Unfortunately, in many cases, patients did not survive the treatment.

In the case of the child from Rouen, it appears that the mercury treatment ultimately led to mercury poisoning. Based on the concentration of mercury found in the child’s bones and teeth, the researchers suggest that the child was likely treated with mercury in the final months of his life, leading to severe poisoning that contributed to his untimely death. It is a tragic reminder of the risks associated with early medical treatments and the human cost of medical experimentation in an era of limited scientific knowledge.

Conclusion: The Legacy of 19th-Century Medicine and the Dangers of Medical Ignorance

This study highlights the grim realities of medical practices during the 19th century, a time when the line between medical knowledge and dangerous experimentation was often blurred. The child’s suffering, as revealed through modern scientific techniques, serves as a poignant reminder of the dark side of historical medicine, where the use of mercury and other toxic substances was not only widespread but also considered a legitimate form of treatment.

Today, we know the devastating effects of mercury poisoning, but in the 19th century, such knowledge was not available. The study of this child’s remains offers valuable insights into the history of medicine and underscores the importance of scientific progress in improving healthcare practices. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of medical practices that lack proper scientific understanding, a lesson that continues to be relevant in today’s world of rapidly advancing medical technologies and treatments.

As we continue to make strides in understanding human health and disease, it is essential to remember the mistakes of the past and ensure that the lessons learned from these tragic stories help guide us toward safer, more effective medical practices in the future.

Reference: Alexandra Zinn et al, Archeometric detection of mercury: A paleopharmacological case study of skeletal remains of a child with vitamin deficiencies (Rouen, France, late 18–19th centuries), International Journal of Paleopathology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2025.02.006