Paleontology, the study of ancient life through fossils, often brings us insights into the distant past, revealing life forms that once thrived on Earth. However, an extraordinary discovery by two Paleontology and Evolution students at the University of Bristol has revealed a truly unique snapshot of prehistoric life. For the first time ever, a study has been conducted on fossils trapped within a neptunian dike—a deep, fissure-like structure in the earth’s crust formed by ancient tectonic movements. What makes this discovery so fascinating is not just the unusual nature of these fossil deposits but the extraordinary mixture of marine and terrestrial species found together, offering a rare glimpse into the ecological dynamics of the Late Triassic period over 200 million years ago.

The Neptunian Dike Mystery

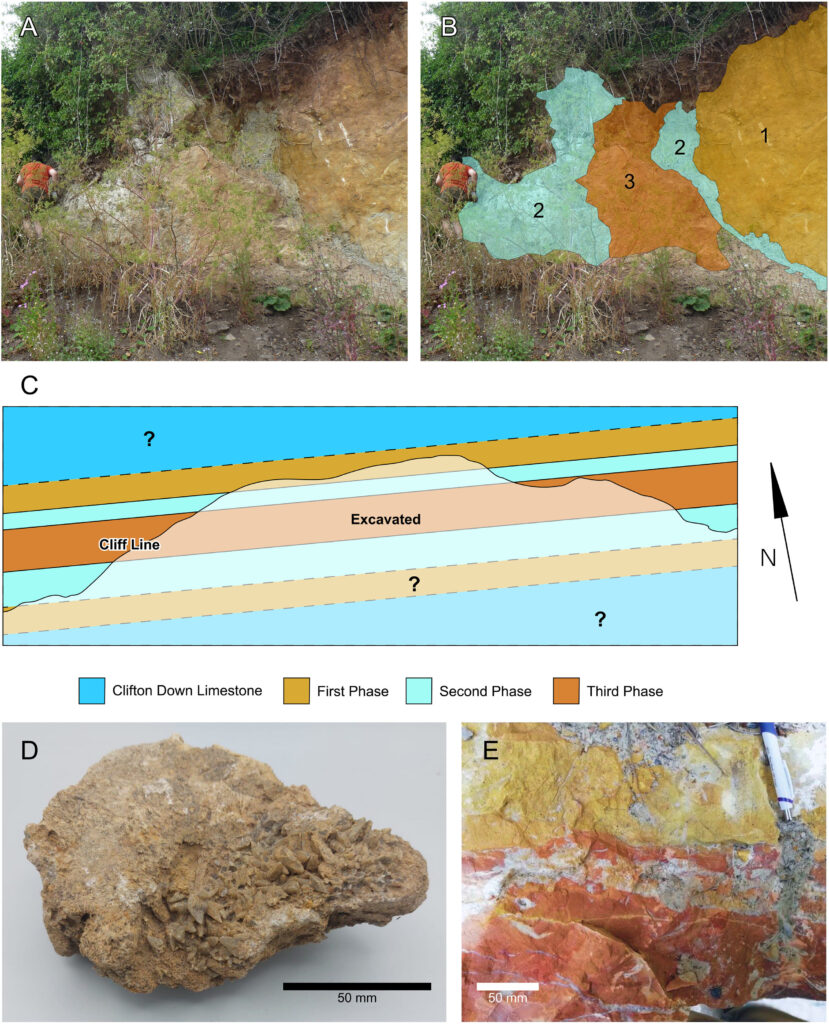

In the Mendip Hills of Somerset, England, two Master’s students, Oliver Weeks and Rebecca Cooper, undertook an ambitious project to explore a neptunian dike. These geological formations are long, mud-filled fissures that cut into older rock layers, and though they are not typically associated with fossil preservation, they sometimes contain remarkable records of the ancient past. Neptunian dikes were likely created by the pressure of tectonic movements, which occurred during the initial splitting of the Atlantic Ocean over 200 million years ago. These movements resulted in faults that acted like giant vacuum tubes, drawing in mud, sand, and the organic remains scattered across the seabed, including fossils.

While such dikes are generally not known for preserving fossils, the one that Weeks and Cooper analyzed yielded a stunning variety of remains. Their discovery is the first detailed study to describe the fossil assemblages trapped in such dikes, offering an unprecedented glimpse into the marine and terrestrial ecosystems of the Late Triassic period.

The Late Triassic World: A Tropical Island Ecosystem

Around 200 million years ago, during the Late Triassic period, the area now known as Bristol and South Wales was dominated by warm, shallow seas. These seas washed over an archipelago of limestone islands, some of which were home to early mammals, dinosaurs, and unique reptiles such as sphenodontians. Sharks, ichthyosaurs, and other marine reptiles patrolled the shallow waters offshore, while the land hosted an assortment of creatures, from early dinosaurs to other, smaller, land-dwelling reptiles.

At this time, the landscape was strikingly different from what we see today. The Earth’s continents were arranged differently, and what are now hills, like the Mendips, were islands in a vast tropical sea. The seas were much higher, with sea levels about 50 meters higher than present. These islands were teeming with life, and the fossil evidence retrieved from the neptunian dikes of the Mendip Hills showcases the biodiversity of both the land and sea at this unique point in Earth’s history.

The Discovery: A Unique Mix of Fossils

The remarkable nature of Weeks and Cooper’s discovery lies in the extraordinary mixture of marine and terrestrial fossils found together in the same stratigraphic layer. This is extremely rare, as fossils from land and sea environments are usually found in separate locations. But within the neptunian dike they studied at Holwell, near the southern Mendip Hills, fossils of both sea creatures and land-dwelling reptiles were discovered in a haphazard yet intriguing mix.

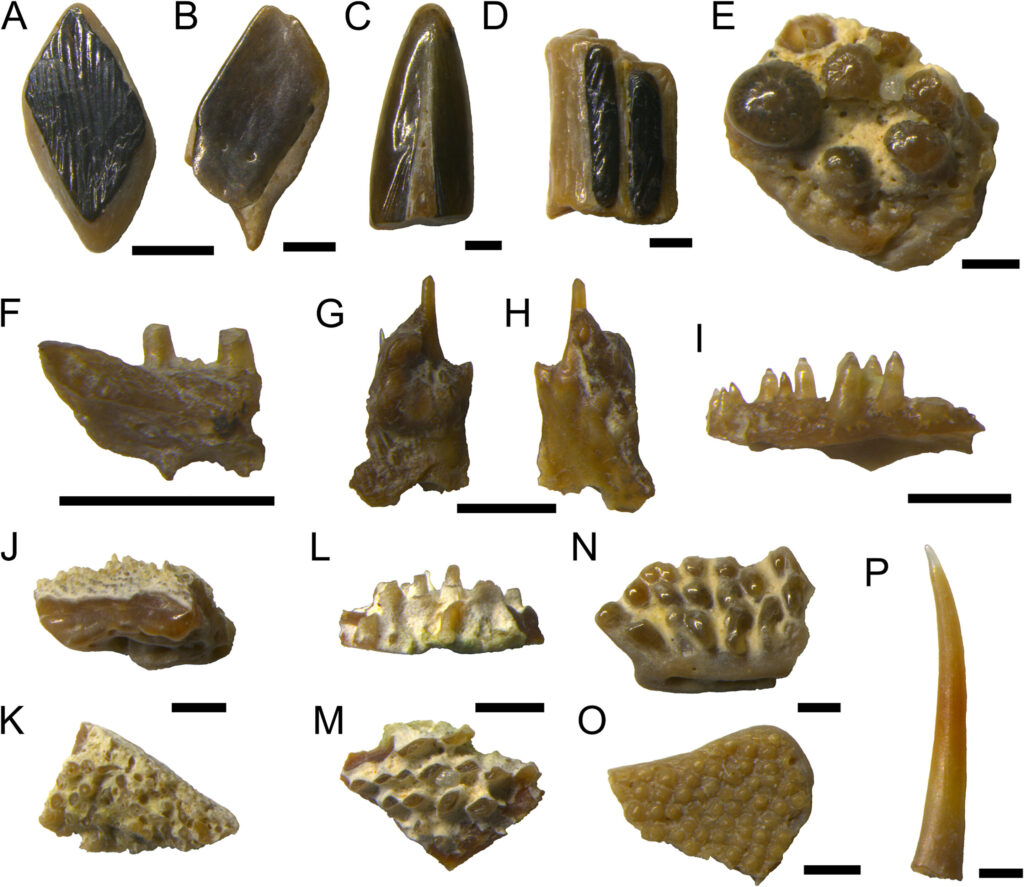

The fossil assemblage included the remains of sharks and other fishes, which likely came from the nearby waters, as well as bones from land reptiles such as sphenodontians, early relatives of modern reptiles. The sphenodontians were small, lizard-like creatures that fed on insects and vegetation, and they may have wandered into the shallow waters or become trapped in the rising waters. The fossilized bones and teeth found at this site paint a picture of an ecosystem that was connected, though often separated by the natural barriers of land and sea.

Weeks explained that the fossils found in the neptunian dike closely resembled those found in other Triassic deposits in the Bristol area, leading them to date the fossils to around 202 million years ago. This date corresponds to the Westbury Formation, an area of rock that contains similar fossils. He and Cooper were particularly excited to discover reptile bones alongside the fish teeth, as it allowed them to piece together an ecological story that bridged the gap between land and sea. This discovery also suggests that there may have been ecological separation between the northern and southern coasts of the ancient Mendip Island, which provided new insights into the geographical and environmental distinctions of the time.

A Unique Snapshot of Prehistoric Life

Professor Mike Benton, who supervised the project, was also astounded by the find. Marine reptiles such as placodonts, large, bulky swimming creatures that had flat, broad teeth for crushing mollusks, were among the fossilized remains found at the site. These creatures likely lived in shallow waters, feeding on the abundant mollusk beds found along the coastline. The presence of such marine species was not surprising, but the addition of land-dwelling reptile bones was unexpected.

Dr. David Whiteside, another supervisor on the project, noted the discovery of sphenodontian bones, which added an interesting dimension to the study. These small, herbivorous reptiles would have lived on land, feeding on plants and insects. Their presence in the fossil assemblage suggested that these terrestrial species somehow became incorporated into the marine environment, perhaps as a result of rising water levels or other ecological factors.

This mixed fossil assemblage has provided new insights into the Late Triassic period, revealing the interconnectedness of the marine and terrestrial ecosystems. The discovery suggests that there may have been more interaction between land and sea than previously thought, with land animals potentially venturing into the shallow waters or being swept into the ocean by rising sea levels or storms.

Honoring Past Work and Pushing Forward

The research team’s work was not just about uncovering new fossils—it also involved revisiting historical records and acknowledging the contributions of past researchers. Much of the fieldwork conducted by Weeks and Cooper built upon the work of Charles Copp, a posthumous author who had made important discoveries in the area during the 1970s. Copp’s work laid the foundation for the investigation of these neptunian dikes, and the current study honored his contributions by completing the work he had started.

Claudia Hildebrandt, Curator of Geology at the University of Bristol, highlighted the importance of this discovery in offering a glimpse into an ancient tropical island scene, which would have been radically different from the Europe we know today. The area, now at a much higher latitude, was once situated in a warmer climate, closer to the equator, where early dinosaurs and mammals roamed the islands. The fossil evidence from the neptunian dike paints a vivid picture of this lost world, bringing us closer to understanding the ecosystems of ancient Earth.

Deborah Hutchinson, from the Bristol City Museum, also emphasized the importance of the project in preserving and honoring the legacy of Charles Copp. His work, though unfinished, inspired this new generation of researchers to continue exploring the fossil-rich Mendip Hills, ultimately fulfilling the potential of his discoveries.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Paleontological Research

Weeks and Cooper’s study marks a significant milestone in paleontological research, as it not only provides new insights into the Late Triassic ecosystems of ancient Britain but also opens the door for future investigations into neptunian dikes. These rare and often overlooked geological features hold the potential for uncovering more fossilized treasures, shedding light on the ancient connections between marine and terrestrial life.

By exploring the rich fossil assemblages within these ancient fault zones, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the prehistoric world, offering a more complete picture of life during the Triassic period. The study of these fossils is a reminder of the complexity and interconnectedness of life on Earth and the ongoing efforts of paleontologists to uncover the mysteries of our planet’s distant past. The discoveries made by Weeks and Cooper will undoubtedly inspire further research and exploration, keeping the spirit of curiosity and scientific inquiry alive for generations to come.

Reference: Oliver J. Weeks et al, Microvertebrates from a Rhaetian neptunian dyke at Holwell, Somerset: Dating the fissures, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2025.101112