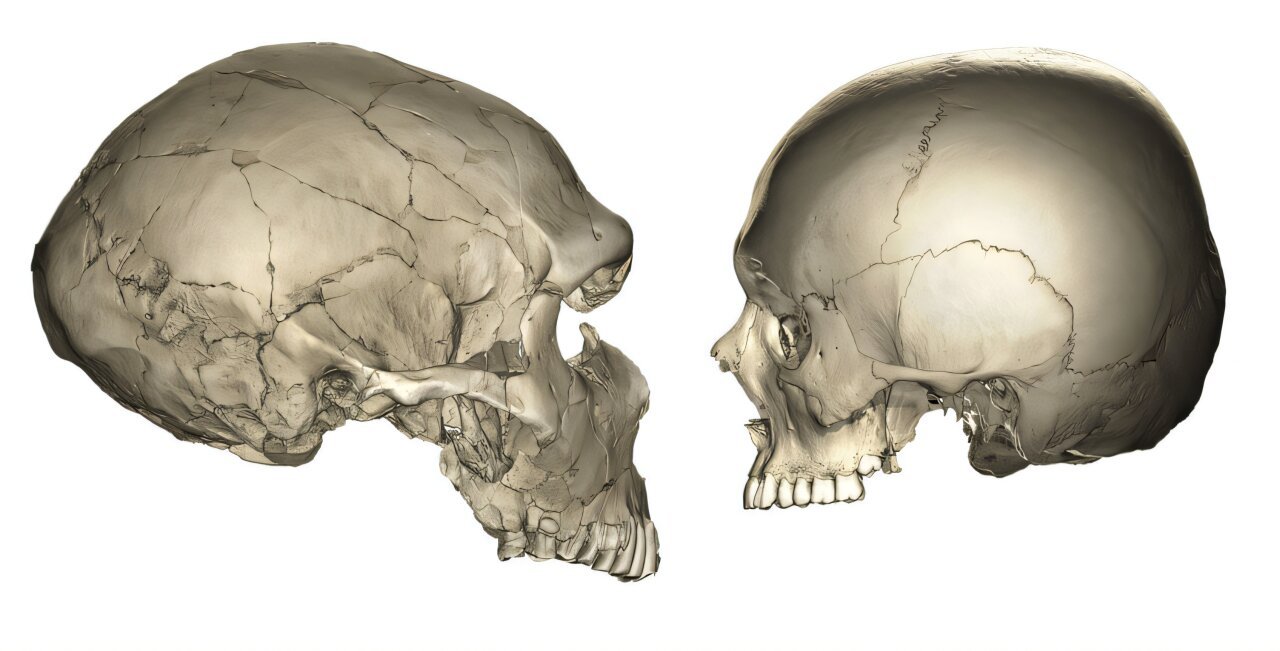

The human face is strikingly distinct from that of our closest evolutionary relatives, such as Neanderthals and other ancient hominins. It is significantly smaller, more refined, and less robust compared to our fossil ancestors. While it is well known that our facial structure has evolved over thousands of years, the reasons behind this transformation have remained largely elusive.

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology has shed light on this mystery, revealing that the human face became smaller due to a fundamental shift in growth patterns. Unlike Neanderthals and chimpanzees, whose faces continue to grow for a prolonged period, human facial growth halts much earlier—around adolescence. This shift in development has played a crucial role in shaping the unique facial characteristics of modern humans.

The Role of Development in Facial Evolution

“Our findings reveal that a change in development—particularly during late growth stages—led to smaller faces,” explains Alexandra Schuh, the study’s first author. “Compared to Neanderthals and chimpanzees who continue growing longer, human facial growth stops earlier, around adolescence, resulting in a smaller adult face.”

This difference in developmental timing, known as heterochrony, is one of the primary factors that differentiate Homo sapiens from our fossil cousins. By stopping facial growth earlier, humans developed a more gracile (delicate and refined) face, which contrasts sharply with the robust and protruding faces of Neanderthals.

The research, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, used an extensive dataset to analyze the ontogeny (growth and development) of facial structures from infancy to adulthood across multiple species. The researchers tracked changes in facial size over time, comparing human growth patterns with those of Neanderthals and chimpanzees. They found that Neanderthals and other hominins experienced prolonged facial growth, which contributed to their more prominent features, including larger nasal cavities, pronounced brow ridges, and a forward-projecting midface.

In contrast, human facial growth slows and eventually ceases during adolescence, leading to a flatter face, smaller jaw, and reduced brow ridges. This process, known as cranial gracilization, has been a defining feature of Homo sapiens.

Bone Cellular Activity and the Halting of Growth

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study was the analysis of bone cellular activity, which provided a deeper understanding of the biological mechanisms that drive these developmental differences. The researchers observed that the decline in bone cellular activity in humans closely mirrors the cessation of facial growth during adolescence.

In other words, as humans reach a certain stage of development, the biological signals that drive facial bone growth begin to fade. This is a stark contrast to Neanderthals, who retain active bone growth for a longer period, contributing to their larger and more pronounced facial structures.

“Identifying key developmental changes allows us to understand how species-specific traits emerged throughout human evolution,” says Schuh. “These results highlight parts of the mechanisms behind cranial gracilization, a process that has shaped the morphology of our species.”

Why Did the Human Face Become Smaller?

The reduction in facial size in Homo sapiens raises an important question: why did evolution favor a smaller and more refined face in our species? Scientists have proposed several hypotheses to explain this evolutionary shift.

1. Dietary Changes and Cooking

One of the leading theories suggests that dietary changes played a significant role in the evolution of the human face. Early humans developed cooking and food processing techniques that made food easier to chew, reducing the need for strong, powerful jaws and large teeth. Unlike Neanderthals, who relied heavily on raw meat and tough plant materials that required intensive chewing, Homo sapiens benefited from softer, more processed diets.

As a result, the evolutionary pressures that favored large jaws and pronounced chewing muscles diminished, leading to the gradual reduction of facial size. This theory aligns with archaeological evidence showing that early humans used tools and fire to prepare food, which significantly changed their eating habits.

2. Speech and Social Communication

Another compelling explanation for the shrinking human face is the development of speech and complex social communication. A smaller, more refined face may have been an advantage for producing a wider range of vocal sounds.

Neanderthals, with their larger and forward-projecting faces, may have had more difficulty producing certain speech sounds compared to modern humans. In contrast, the flatter faces and smaller mouths of Homo sapiens may have facilitated the development of clear and precise vocalizations, ultimately contributing to the rise of complex language.

Language was a crucial advantage for early humans, allowing them to collaborate, share knowledge, and form larger social groups. This capability would have provided a significant survival advantage, reinforcing the evolutionary trend toward smaller, more expressive faces.

3. Reduced Aggression and Social Cooperation

Some researchers propose that the evolution of a smaller face is linked to reduced aggression and increased social cooperation. Studies of domesticated animals, such as dogs and foxes, have shown that selection for reduced aggression often results in smaller facial features and more juvenile traits—a phenomenon known as “self-domestication.”

Similarly, humans may have undergone a process of self-domestication, where individuals with more sociable and cooperative tendencies were favored by natural selection. A smaller face, with a less pronounced brow ridge and a more rounded appearance, may have been a signal of reduced aggression, promoting group cohesion and cooperation.

This theory aligns with research on human social behavior, which suggests that our ancestors gradually developed less aggressive tendencies, allowing for larger, more complex societies to emerge.

The Future of Facial Evolution

As human lifestyles continue to evolve, so too may our facial features. With advances in medicine, nutrition, and technology, modern humans are no longer subjected to the same evolutionary pressures as our ancestors. Some scientists speculate that our faces may continue to change in response to our environment, diet, and social behaviors.

For example, as people increasingly rely on technology and speech-based communication, facial muscles and structures related to expression and articulation may continue to evolve. Similarly, as diets become even more processed and require less chewing, jaw sizes could continue to shrink over generations.

However, because natural selection no longer plays as dominant a role in shaping human evolution due to medical and technological advancements, any changes are likely to be slow and subtle.

Conclusion

The human face is a product of millions of years of evolution, shaped by changes in growth patterns, diet, social behavior, and communication. The research from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology provides a critical piece of the puzzle, revealing that the early cessation of facial growth in adolescence played a key role in making our species distinct from Neanderthals and other fossil relatives.

By understanding the biological mechanisms behind our unique facial structure, scientists can gain deeper insights into the evolutionary forces that shaped Homo sapiens. Whether through dietary adaptations, language development, or social cooperation, the human face continues to be a fascinating reflection of our evolutionary journey.

As we move forward into the future, it remains to be seen whether our faces will continue to evolve in response to modern lifestyles. But one thing is certain—our small, refined, and expressive faces have been a defining feature of what it means to be human.

Reference: Alexandra Schuh et al, Human midfacial growth pattern differs from that of Neanderthals and chimpanzees, Journal of Human Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103667