The night sky has always been a canvas of wonder, a window through which humanity has gazed for millennia, pondering the mysteries of existence. For ancient civilizations, the stars were eternal fires kindled by gods, the Milky Way a river flowing through the heavens. Today, equipped with titanic telescopes and minds sharpened by science, we look beyond the stars to discover objects so distant and ancient that they seem to belong to another reality entirely. One of the most astonishing finds of our cosmic exploration has been the farthest galaxy ever discovered, a faint ember from the universe’s primordial dawn—a time when existence itself was still new.

This is the story of that galaxy, its incredible distance, and what it reveals about our universe’s earliest moments. In telling this tale, we’ll journey back across unimaginable expanses of space and time to witness the universe in its infancy. We’ll also explore how astronomers push the limits of technology and theory to glimpse these cosmic relics, and why finding the most distant galaxies matters more than we might think.

The Quest to See the First Light

Before we dive into specifics, let’s understand why the search for distant galaxies matters. Observing faraway objects in space isn’t just a hobby for star-struck astronomers; it’s a form of time travel. Because light doesn’t move instantaneously—it travels at 299,792 kilometers per second (about 186,000 miles per second)—looking farther into space means looking deeper into the past.

Light from nearby objects—say, the Moon—takes just over a second to reach Earth. Light from the Sun takes eight minutes. But the light from the most distant galaxies has been traveling toward us for over 13 billion years. That means when we observe these ancient structures, we’re seeing them as they existed eons ago, long before our Sun, Earth, or even the Milky Way formed.

This pursuit isn’t just about breaking records. Each distant galaxy is a cosmic time capsule that offers clues to how galaxies form, how stars ignite, and how the universe evolved from a near-empty darkness into the rich, star-filled expanse we see today. Peering into the distant past helps answer some of the biggest questions in cosmology: Where did we come from? How did it all begin? What forces shaped the first galaxies, and by extension, everything else?

How Distance Is Measured in the Universe: The Redshift Yardstick

Before we introduce the current record-holder for the farthest known galaxy, we need to understand how astronomers measure cosmic distances. In astronomy, we don’t usually think in terms of miles or kilometers because the numbers quickly become incomprehensible. Instead, scientists often describe how far away something is by its “redshift.”

Redshift refers to the way light stretches as the universe expands. When a galaxy moves away from us, its light shifts toward longer (redder) wavelengths, similar to how a siren lowers in pitch as an ambulance speeds away. The higher the redshift number (denoted by z), the farther away—and earlier in time—a galaxy is.

A redshift of z = 1 means we’re seeing an object as it was when the universe was roughly half its current age. A redshift of z = 6 pushes us back to when the cosmos was less than a billion years old. Beyond z = 10, we approach the epoch when the first stars and galaxies blinked into existence.

GN-z11: The Former Record Holder

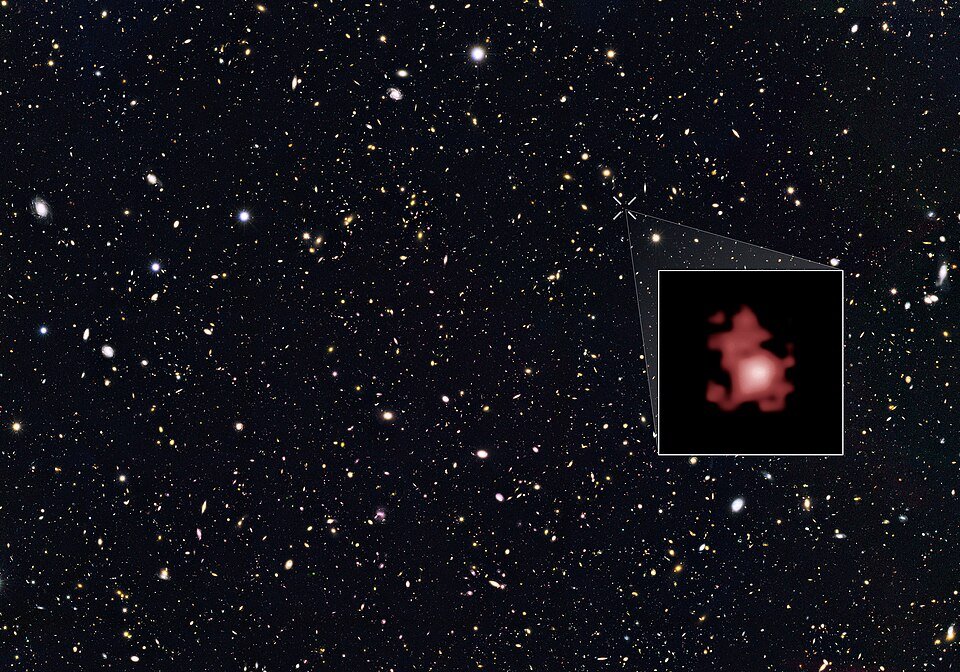

For many years, the title of “farthest known galaxy” belonged to GN-z11, discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2015. GN-z11 is not just far away—it’s very far away. Its redshift is z = 11.09, which means the light we see from it has traveled for about 13.4 billion years. When that light began its journey, the universe was just 400 million years old—a mere 3% of its current age.

GN-z11 is remarkable for other reasons, too. Despite existing so soon after the Big Bang, this galaxy is surprisingly bright and massive. It’s forming stars at a furious rate, producing new suns 20 times faster than the Milky Way. This raises questions about how galaxies could grow so large, so quickly after the universe’s dark ages—an era after the Big Bang when the universe was filled with neutral hydrogen, and stars had yet to reionize the cosmos.

For years, GN-z11 stood as the most distant confirmed galaxy, a beacon from the early universe. But as technology advanced, astronomers kept pushing deeper, until GN-z11’s reign was eclipsed.

Enter GLASS-z13: A New Champion Emerges

In 2022, everything changed. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), humanity’s most powerful space observatory, began peering into the universe with unprecedented clarity. Within just days of its first data release, astronomers spotted a galaxy even farther away than GN-z11.

This new contender was dubbed GLASS-z13 (short for “Grism Lens-Amplified Survey from Space”). With an estimated redshift of z ≈ 13.1, GLASS-z13 appears to us as it was just 300 million years after the Big Bang. That makes it the farthest galaxy ever confirmed—a mind-bending 33 billion light-years away when accounting for the universe’s expansion.

At first glance, GLASS-z13 appears as a faint smudge in JWST’s data. But this little smear of light holds tremendous significance. It suggests that galaxies formed far earlier than we thought possible, and in greater numbers.

How Big and Bright Is GLASS-z13?

Despite being so ancient, GLASS-z13 is unexpectedly large. It’s estimated to be around 1 billion solar masses, about 1% of the Milky Way’s mass today—but remember, it reached this size only 300 million years after the Big Bang! Its physical size is relatively compact, likely spanning just a few thousand light-years, but it’s burning brightly in infrared wavelengths, indicating it’s already well into a star-forming phase.

The presence of such a mature galaxy so early on has forced astronomers to revisit models of galaxy formation. According to previous theories, it should have taken longer for such a massive system to emerge. GLASS-z13 implies that either the first stars and galaxies formed rapidly, or the physics of the early universe is more complex than we realized.

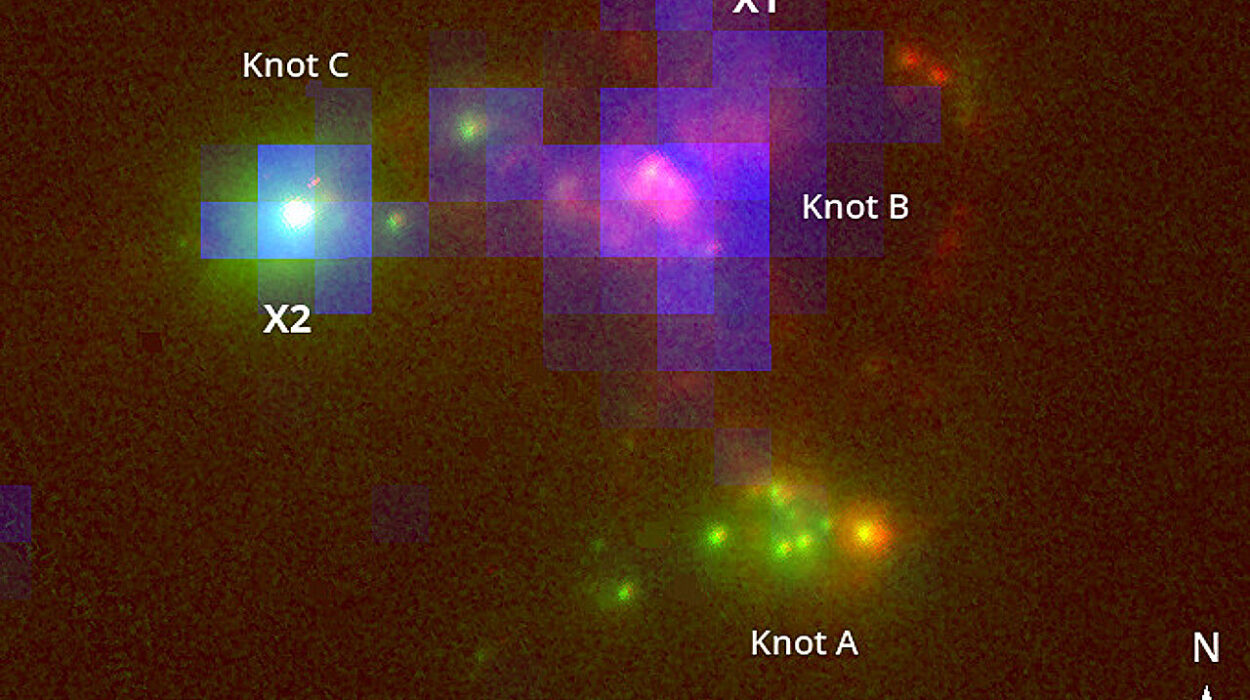

Peering Even Farther: The Case of CEERS-93316 (z ≈ 16?)

Hot on the heels of GLASS-z13, another discovery hinted at an even more distant galaxy: CEERS-93316. Detected in JWST’s CEERS (Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science) survey, CEERS-93316 initially showed signs of being at a redshift z ≈ 16.4, corresponding to just 250 million years after the Big Bang. If confirmed, it would smash all previous records.

However, caution is warranted. Early redshift estimates often come from photometric data, measuring how a galaxy’s light is filtered through different wavelengths. For absolute confirmation, astronomers need spectroscopic redshifts, which provide a precise measurement of how much the light has stretched. Sometimes photometric redshifts overestimate an object’s distance. In the case of CEERS-93316, further spectroscopic observations are ongoing to confirm its record-breaking status.

What Do These Distant Galaxies Tell Us?

These ancient galaxies aren’t just distant points of light. They offer profound insights into the earliest chapters of cosmic history.

1. The Speed of Galaxy Formation

The discovery of massive galaxies at such early times challenges our understanding of how galaxies assemble. According to prevailing cosmological models, gas should take time to cool and clump together after the Big Bang. Yet GLASS-z13 and others suggest galaxy formation was incredibly rapid.

2. The First Stars and Cosmic Reionization

These early galaxies are likely filled with the universe’s first generation of stars—Population III stars. These stars are thought to be massive, hot, and short-lived, producing intense ultraviolet radiation that reionized the hydrogen fog filling the early cosmos. Observing galaxies like GLASS-z13 helps scientists understand how the universe transitioned from darkness to light during the epoch of reionization.

3. Testing Dark Matter and Cosmology

The way galaxies form and grow depends heavily on dark matter—an invisible substance that makes up 85% of the universe’s matter content. The early appearance of massive galaxies might require new thinking about how dark matter behaves, or even hint at new physics beyond the standard cosmological model.

How We Find These Ancient Beacons: The Power of JWST

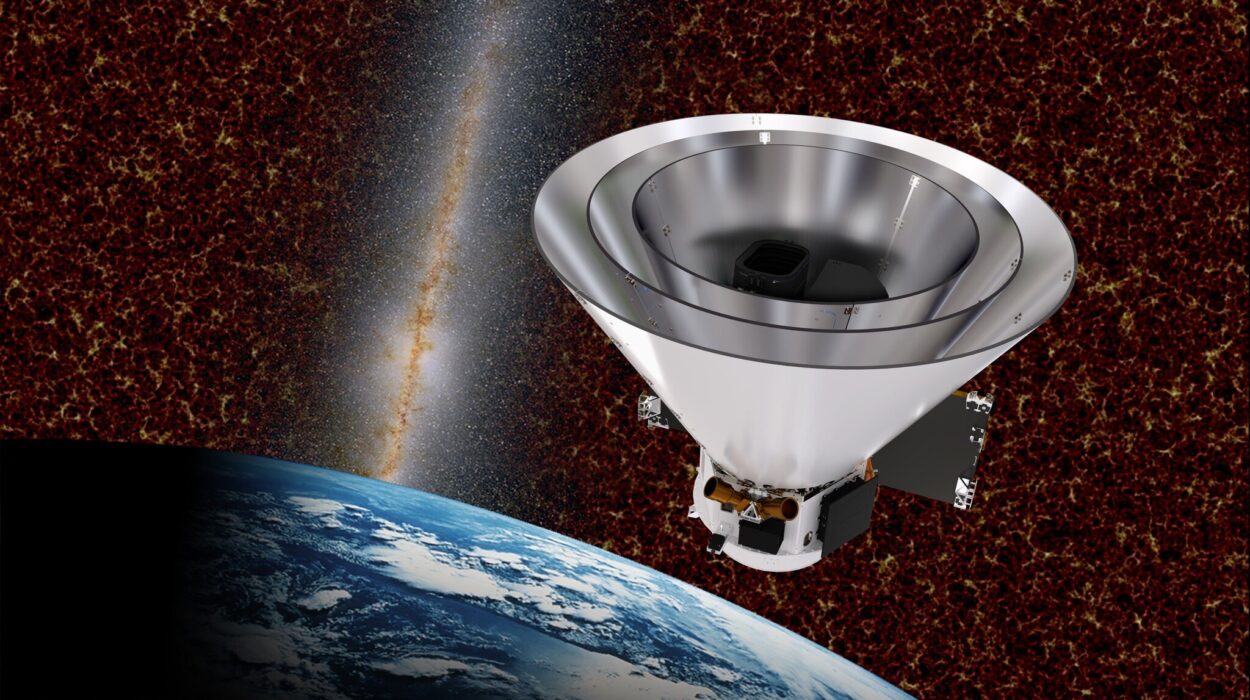

The James Webb Space Telescope is revolutionizing astronomy. Unlike its predecessor Hubble, which primarily observed in visible and ultraviolet light, JWST is optimized for infrared. This is crucial for spotting ancient galaxies because their light has been stretched into the infrared due to cosmic expansion.

JWST’s main infrared camera, NIRCam (Near Infrared Camera), can see objects that are faint and redshifted beyond what Hubble could detect. Its spectrograph, NIRSpec, provides detailed spectroscopic redshifts that confirm a galaxy’s distance.

JWST’s giant gold-coated mirror (6.5 meters in diameter) collects more light than any previous space telescope, allowing it to peer farther and resolve fainter objects. As JWST continues its surveys, it’s expected to find galaxies at redshifts z = 20 or beyond—within 200 million years of the Big Bang.

The Challenges of Confirming Distance

Measuring the distance to these faint galaxies is tricky. Photometric redshifts rely on colors, but contaminants can fool astronomers. For example, closer galaxies full of dust can mimic the appearance of high-redshift galaxies. Only through spectroscopic observations can scientists confirm whether these objects truly lie at the edge of the observable universe.

JWST’s spectroscopic capabilities have already validated some early candidates. Still, confirming these ultra-distant galaxies requires time and effort, often using multiple instruments in space and on the ground.

A Glimpse of the Primordial Universe

When we gaze at GLASS-z13, GN-z11, or CEERS-93316, we are looking at cosmic infants in a universe barely out of its swaddling clothes. These galaxies represent the dawn of structure, the first steps toward the universe we know today. They are the ancestors of every galaxy—including our own Milky Way—and every planet, star, and living being.

The study of these distant galaxies helps refine our understanding of the Big Bang, cosmic inflation, and the formation of large-scale structure. They shed light on the processes that seeded galaxies, stars, and ultimately life itself.

The Road Ahead: The Hunt Continues

JWST’s mission has only just begun. Over the next decade, it will uncover hundreds, perhaps thousands, of galaxies from the universe’s first few hundred million years. Each discovery will add new brushstrokes to the grand painting of cosmic history.

Future missions, like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (set to launch in the 2030s), will complement JWST by surveying even larger portions of the sky for early galaxies. Ground-based observatories, such as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile, will follow up with detailed observations.

Astronomers also hope to directly observe Population III stars and pinpoint the moment of cosmic reionization. These observations will mark the final frontier of the “cosmic dawn.”

Conclusion: Touching the Edge of Forever

The discovery of the farthest galaxy ever observed is more than an astronomical achievement—it’s a philosophical one. To see light that has traveled for over 13 billion years is to witness the earliest chapters of the universe’s epic story. It reminds us that we are part of a cosmos that has been evolving for eons, and that our own existence is connected, however distantly, to those first flickers of light in the primordial dark.

Every time we look farther into the universe, we look closer to the beginning. In the faint, ancient glow of galaxies like GLASS-z13, we catch glimpses of our own origin. And as our telescopes reach deeper into the void, who knows what other ancient wonders are waiting to be found?

The universe is vast. Its earliest light is faint. But as long as we keep looking up, we will continue to touch the edge of forever.