For millennia, humanity has stared up at the stars, wondering if we are alone. We imagined other worlds, distant planets circling foreign suns, harboring life or civilizations far beyond our reach. These ideas populated our myths, our stories, and later our science fiction. But until just a few decades ago, these worlds were only speculation.

The discovery of exoplanets—planets orbiting stars outside our solar system—changed everything. These alien worlds became a reality, not just in the pages of novels or the realms of imagination, but in the telescopic observations and data sheets of scientists. And then came something even more extraordinary: we saw them.

In the vastness of space, where stars gleam like distant candles and planets are tiny, dark specks lost in the glare of their suns, astronomers managed to capture the first direct images of these distant worlds. It was a monumental achievement. Seeing is believing, and with these images, we stepped into a new age of discovery.

This is the story of those first images—how they were captured, why they matter, and where they might lead us.

A Brief History of Exoplanet Hunting: From Hints to Proof

Before we delve into the images themselves, it’s worth appreciating just how hard it is to even find a planet around another star, let alone photograph one.

For centuries, astronomers searched for signs of other worlds. The first solid evidence came not from images but from indirect methods. In 1992, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of planets orbiting a pulsar—a spinning neutron star. These were not the idyllic Earth-like planets we’d dreamed of; they were bizarre worlds orbiting a dead star. But they were exoplanets.

In 1995, the first planet orbiting a Sun-like star, 51 Pegasi b, was found using the radial velocity method—detecting the subtle wobble in a star’s motion caused by the gravitational pull of an orbiting planet. From there, the floodgates opened. Thousands of exoplanets have been found using radial velocity and another indirect method called the transit method, which looks for tiny dips in a star’s brightness as a planet crosses its face.

But these methods, while powerful, are like hearing footsteps without seeing who makes them. What we craved was a direct view, an actual image of an exoplanet. That was a far taller order.

The Challenge: Why Photographing Exoplanets is So Hard

Imagine trying to spot a firefly next to a floodlight. Now imagine doing it from thousands of miles away. That’s what it’s like trying to directly image an exoplanet. Stars are blazingly bright; their light outshines any nearby planet by factors of millions or billions. Planets don’t emit their own light (at least not in visible wavelengths); they reflect the starlight, and that reflection is faint—like a grain of dust next to a bonfire.

The glare from a star easily drowns out the faint glow of its planets. On top of that, Earth’s atmosphere adds to the difficulty, distorting the incoming starlight and blurring the image.

Astronomers needed a combination of cutting-edge technology, clever tricks, and a whole lot of patience to overcome these challenges. Enter coronagraphs, adaptive optics, and infrared imaging—the game-changers.

The Breakthrough: 2M1207b – The First Image of an Exoplanet

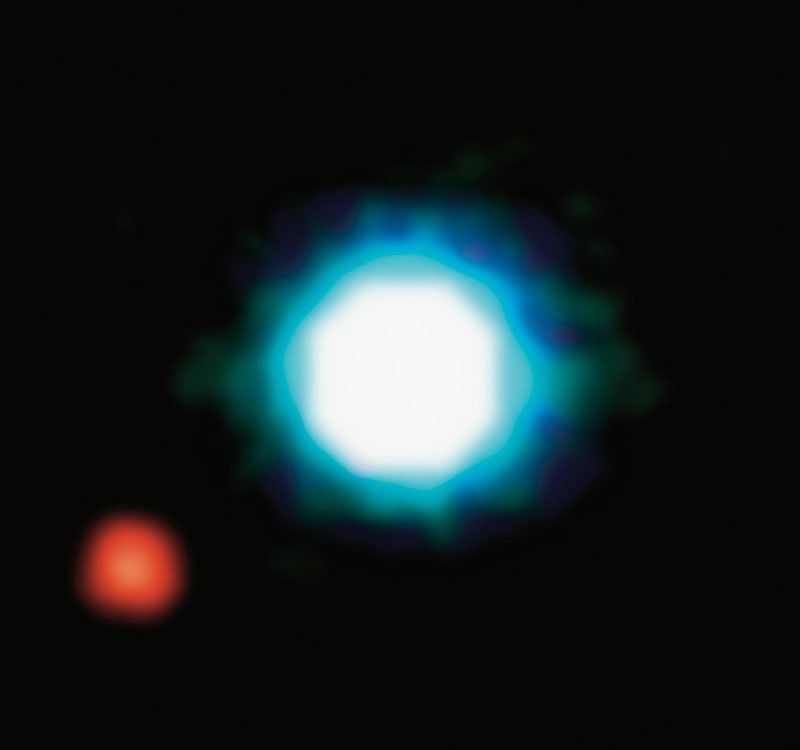

The honor of being the first directly imaged exoplanet goes to 2M1207b, a massive gas giant orbiting a brown dwarf star, 2M1207, about 170 light-years away in the constellation Centaurus.

Discovery and Imaging (2004)

In April 2004, using the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, astronomers led by Gaël Chauvin managed to directly capture the first image of an exoplanet. It wasn’t orbiting a Sun-like star, but rather a brown dwarf—a failed star, too massive to be a planet, yet not massive enough to ignite nuclear fusion like a true star.

The planet itself, 2M1207b, is a super-Jupiter, estimated to be four times the mass of Jupiter. It orbits its brown dwarf parent at a distance of about 40 astronomical units (AU)—more than the distance between Pluto and the Sun in our solar system. Because the brown dwarf is relatively dim, and the planet is young and still glowing from the heat of its formation, it was visible in infrared light.

The image wasn’t exactly a stunning color photograph. It was a faint, pixelated infrared dot next to another faint dot (the brown dwarf). But make no mistake—this was history in the making.

Why It Was a Big Deal

This was the first time humans had laid eyes on a planet circling another star. Before 2M1207b, exoplanets were dots in data charts, numbers in spreadsheets. Now, there was a picture. It was as if we had finally opened a window and glimpsed the neighbors—neighbors living light-years away.

The Next Images: HR 8799 System – A Planetary Family Portrait

If 2M1207b was a proof of concept, the next big imaging success was a jaw-dropper: a family portrait of multiple planets orbiting a single star.

The Star: HR 8799

HR 8799 is a young, massive star located about 129 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. It’s bright and relatively nearby (by cosmic standards), making it a tempting target for planet hunters. In 2008, two independent teams led by Christian Marois and Bruce Macintosh captured images of not one, not two, but three planets orbiting HR 8799. Later observations confirmed a fourth planet in the system.

The Planets

These planets—HR 8799b, c, d, and e—are all gas giants, several times the mass of Jupiter. They orbit far from their star, making them easier to image because they are not lost in its glare. Like 2M1207b, they are young and still radiating heat, which means they glow brightly in infrared light.

What makes HR 8799 special is not just the images but the fact that astronomers were able to track the planets over time, watching them move in their orbits. We could actually see the dynamics of another solar system at play. Time-lapse videos have been created from years of observations, showing the planets dancing around their star. It’s like watching a miniature model of our own solar system, only real.

Tech That Made It Possible: Coronagraphs and Adaptive Optics

Without certain technological marvels, direct imaging of exoplanets wouldn’t have been possible.

Coronagraphs

A coronagraph is a device placed inside a telescope that blocks out the bright light of a star, much like holding your hand up to block the Sun so you can see something nearby. By masking the star’s glare, faint objects nearby—like planets—become visible.

Adaptive Optics

Adaptive optics is another essential tool. Earth’s atmosphere distorts incoming starlight, causing stars to twinkle and blurring images. Adaptive optics systems use rapidly adjusting mirrors to compensate for this distortion, producing sharper images. This allows ground-based telescopes to achieve nearly space-telescope quality resolution.

Together, these technologies made it possible to suppress the overwhelming light from stars and finally glimpse the faint glow of orbiting planets.

Not Just Infrared: Visible Light Images of Exoplanets

Infrared has been the go-to for exoplanet imaging because young, massive planets glow brightly in these wavelengths. But astronomers have also managed to capture visible light images of exoplanets.

In 2008, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope took a visible light image of Fomalhaut b, a planet orbiting the star Fomalhaut, about 25 light-years away. Fomalhaut b caused quite a stir. Initially thought to be a planet, further study revealed it might be a cloud of dust and debris. But it marked the first time we saw anything resembling a planet in visible light.

Whether Fomalhaut b is a true planet or not, the feat of imaging something so faint and close to a star in visible light was another technological milestone.

Why Direct Imaging Matters

Why go to all the trouble of imaging exoplanets directly when other methods can tell us they exist?

Atmospheric Analysis

Direct imaging allows astronomers to analyze a planet’s light directly, rather than inferring its properties from how it affects its host star. By splitting the light into a spectrum, we can study a planet’s atmosphere, composition, and even weather. We’ve detected clouds, carbon monoxide, water vapor, and methane on some of these imaged worlds.

Finding Earth 2.0

Most of the directly imaged exoplanets so far are massive, hot gas giants. But improving technology might one day allow us to image Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of their stars—planets where liquid water, and perhaps life, could exist.

Direct imaging of such worlds could let us detect biosignatures—signs of life, like oxygen or chlorophyll in the atmosphere.

The Future: Telescopes That Will Take Us There

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

Launched in late 2021, JWST is already revolutionizing our understanding of exoplanets. Though not designed primarily for direct imaging, its infrared instruments are studying the atmospheres of distant planets in unprecedented detail.

Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs)

On the ground, next-generation telescopes like the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile, the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) in Hawaii, and the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) will bring unparalleled resolving power and sensitivity. These behemoths will use advanced coronagraphs and adaptive optics to directly image smaller, cooler planets than ever before.

Space Missions: HabEx and LUVOIR

NASA is also planning ambitious space missions like HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Observatory) and LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor), designed specifically to image Earth-like planets in habitable zones and look for signs of life.

Conclusion: The Dawn of a New Era

We once looked to the stars and imagined other worlds. Now we can see them. The first images of exoplanets opened a door, and what lies beyond it is nothing short of breathtaking. Every dot of light we photograph, every atmosphere we analyze, every orbit we trace brings us closer to answering one of humanity’s oldest questions: Are we alone?

The journey has only just begun, and the future promises images not just of distant gas giants, but perhaps of distant oceans, alien continents, and—if we are lucky—signs of life beyond Earth.

From the faint infrared glow of 2M1207b to the future telescopes that will reveal Earth-like planets in glorious detail, the direct imaging of exoplanets has transformed us from dreamers into explorers. The universe is vast, but now, we can finally see the neighbors.

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.