Before the stars, before the galaxies, before light itself—there was darkness.

The early universe, in its infancy, was a place of haunting simplicity. It was an expansive void, silent and dark, shrouded in an endless night that had persisted since the afterglow of the Big Bang began to fade. For hundreds of millions of years, nothing shone. There were no stars to pierce the inky blackness, no galaxies to form luminous islands in the cosmic ocean. The universe was a vast, diffuse sea of hydrogen and helium, the two simplest and lightest elements forged in the fires of the Big Bang.

This period, known by cosmologists as the “Cosmic Dark Ages,” was not entirely empty. Gravity was at work, silently sculpting the future by tugging on tiny ripples in the density of matter. Those ripples would eventually become the seeds of all cosmic structure. But for now, the universe was a void, waiting for its first spark.

And then, something extraordinary happened. The darkness ended. The first stars ignited.

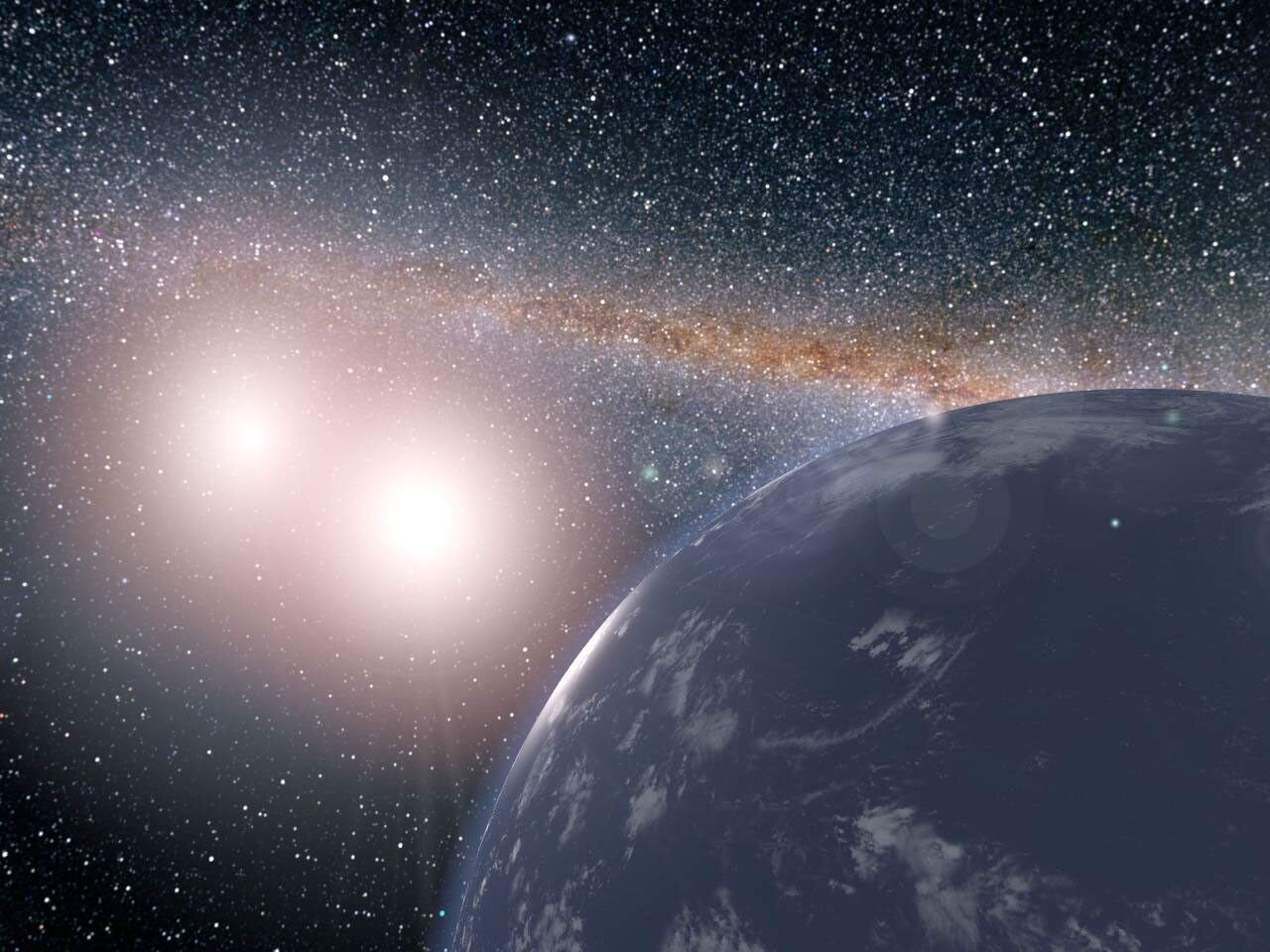

These were no ordinary stars. They were Population III stars—the universe’s pioneers, the first luminous objects to light up the cosmos. They were colossal, powerful, and unlike anything that has existed since. They heralded the dawn of light, forever transforming the universe and paving the way for everything that followed: galaxies, planets, and eventually life itself.

This is their story.

A Universe in Its Infancy

The Aftermath of the Big Bang

The Big Bang was not an explosion in space; it was an explosion of space. It marked the beginning of time, energy, and matter. For a brief moment, the universe was a furnace of unimaginable temperatures and densities. As it expanded, it cooled rapidly. Within minutes, the first atomic nuclei formed in a process known as Big Bang nucleosynthesis, producing mostly hydrogen, with traces of helium and tiny amounts of lithium.

But the universe was still too hot for electrons to bind with these nuclei. It took nearly 380,000 years before things cooled enough for atoms to form, ushering in the era of recombination. During this time, the universe became transparent, releasing the photons we now detect as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)—a faint, ancient glow that still bathes the cosmos today.

After recombination, the universe entered the Cosmic Dark Ages. Neutral hydrogen gas filled space, and though the CMB provided a dim background, no new sources of light had yet appeared.

Gravity Takes the Stage

During these dark millennia, gravity began to assert its influence on matter. The universe was not perfectly smooth; small fluctuations in the density of matter had been seeded during the inflationary epoch shortly after the Big Bang. These slight overdensities were the beginnings of cosmic structure.

Over millions of years, these denser regions grew under gravity’s pull, slowly gathering more and more material into clumps called dark matter halos. Dark matter, a mysterious and invisible form of matter that interacts only through gravity, was instrumental in this process. It acted as the gravitational scaffolding around which ordinary matter (hydrogen and helium gas) could gather and collapse.

Inside these dark matter halos, something remarkable was about to happen. The first stars were about to be born.

The Birth of the First Stars

The Ingredients for a Star

For a star to form, you need a cloud of gas that can collapse under its own gravity. As the gas collapses, it heats up. If the gas can cool efficiently, gravity can continue to compress it until nuclear fusion ignites at the core, creating a star.

But there was a problem.

The early universe had only hydrogen and helium. Heavier elements—what astronomers call metals—are incredibly effective at cooling gas clouds because they can emit radiation at a wide range of wavelengths, allowing the cloud to shed heat as it collapses. But these metals didn’t exist yet. Population III stars were forged from pure, primordial gas, devoid of the heavy elements that make modern star formation relatively easy.

Without metals, the cooling process was inefficient. The gas could not fragment into smaller clumps as easily as it does today. Instead, it formed large, massive clouds. And these clouds gave birth to massive stars.

The Formation Process

Inside dark matter halos, with masses between a hundred thousand and a few million times that of the Sun, the primordial hydrogen and helium gas began to collapse. As the gas fell inward, it heated up to thousands of degrees Kelvin.

The only available cooling mechanism was molecular hydrogen (H₂), which could radiate some of this heat away by emitting photons. But molecular hydrogen was fragile and difficult to form in large amounts. As a result, the gas could only cool so much, leading to the formation of extremely massive stars.

Simulations and theoretical models suggest that Population III stars typically had masses ranging from tens to hundreds of times the mass of the Sun. Some might have been even larger, approaching a thousand solar masses.

These were giants in every sense of the word—brilliant, powerful, and short-lived.

Giants of Light and Fury

The Characteristics of Population III Stars

Population III stars were vastly different from the stars we see today. Modern stars, like our Sun, are made of material that has been recycled many times over by earlier generations of stars. They contain a small but significant fraction of metals, which affect their formation, structure, and evolution.

In contrast, Population III stars were pure. With no metals to cool them effectively, they grew large and hot.

These stars burned bright and fast. The most massive of them were hotter than any stars that have existed since. Their surface temperatures could reach up to 100,000 Kelvin—compared to the Sun’s relatively modest 5,800 Kelvin. They emitted enormous amounts of ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which had profound effects on their surroundings.

Lifespan and Death

The lives of Population III stars were short—cosmically speaking. The most massive among them may have lived for just a few million years before exhausting their nuclear fuel. But in that brief time, they profoundly reshaped the universe.

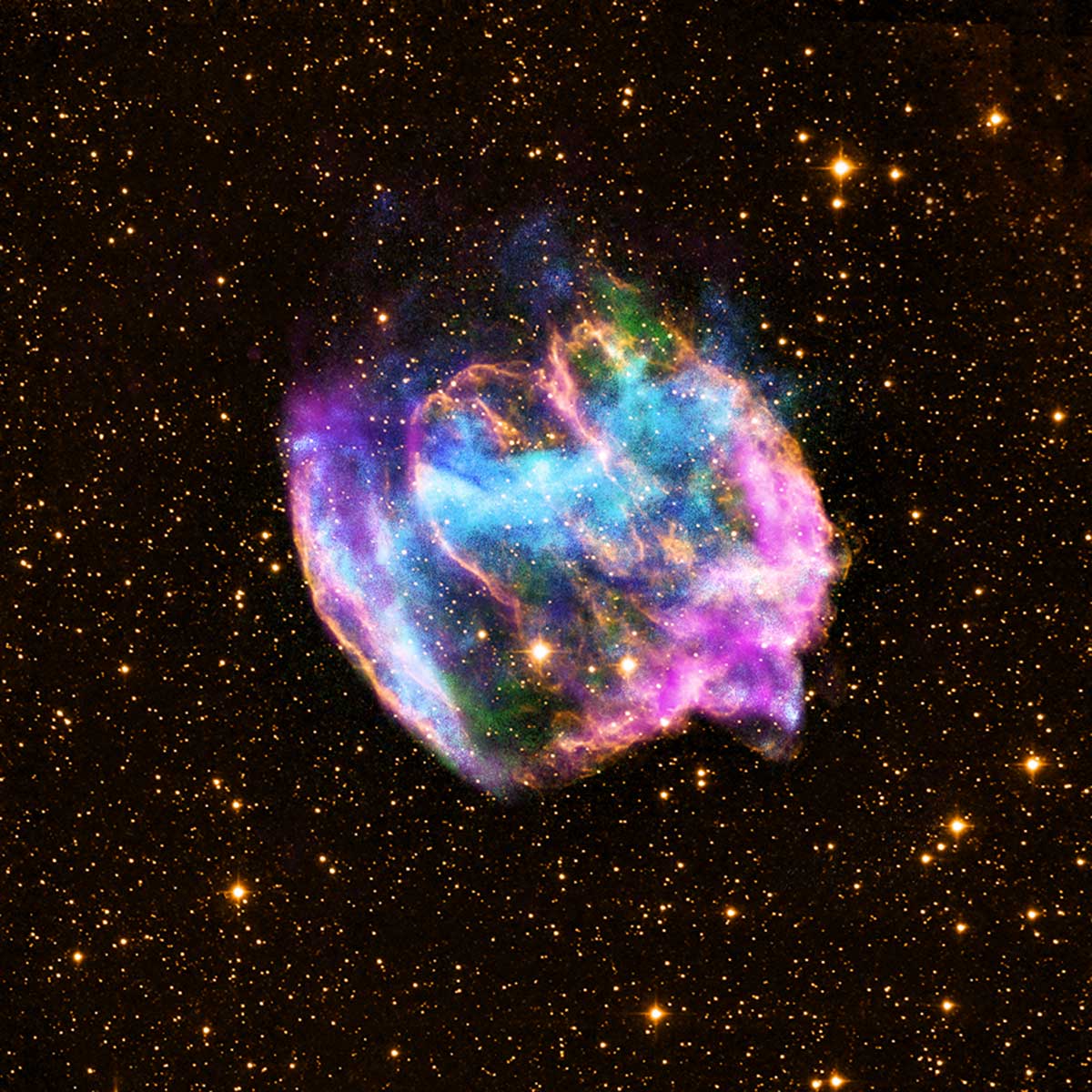

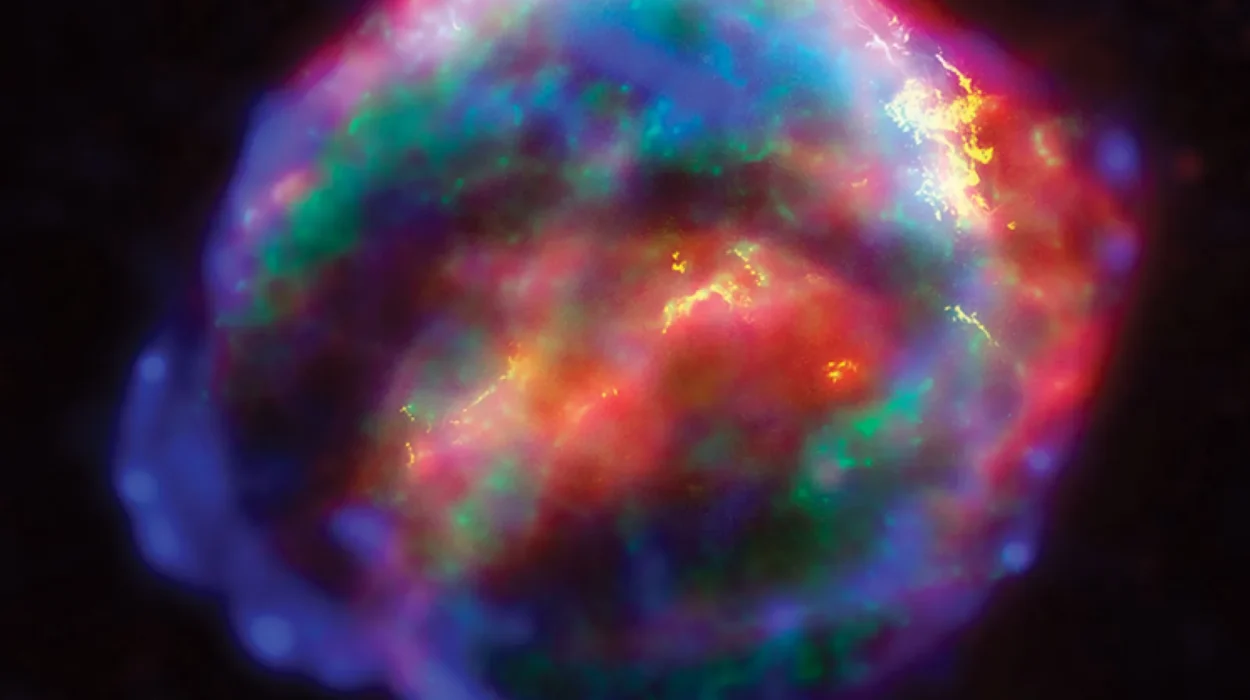

At the end of their lives, these stars died violent deaths. Depending on their masses, they ended in spectacular supernovae or collapsed directly into black holes.

- Stars between 140 and 260 solar masses likely died in pair-instability supernovae, titanic explosions that completely destroyed the star and left nothing behind. These explosions were so powerful that they ejected vast amounts of heavy elements—carbon, oxygen, and beyond—into the surrounding space for the first time.

- Stars less massive than 140 solar masses could end in core-collapse supernovae, similar to modern massive stars, leaving behind neutron stars or black holes.

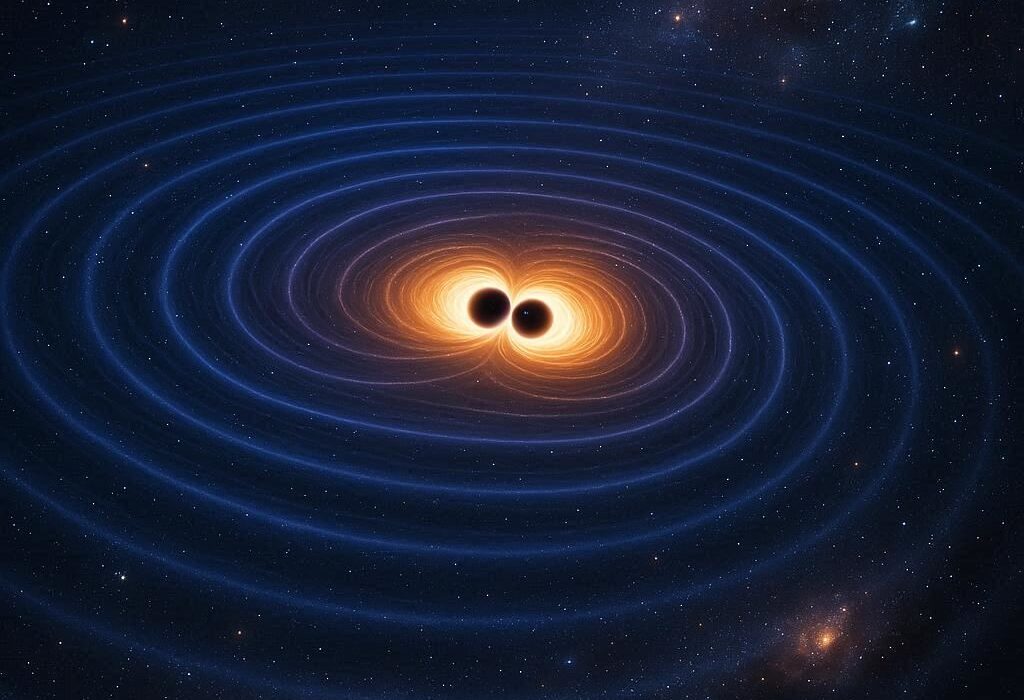

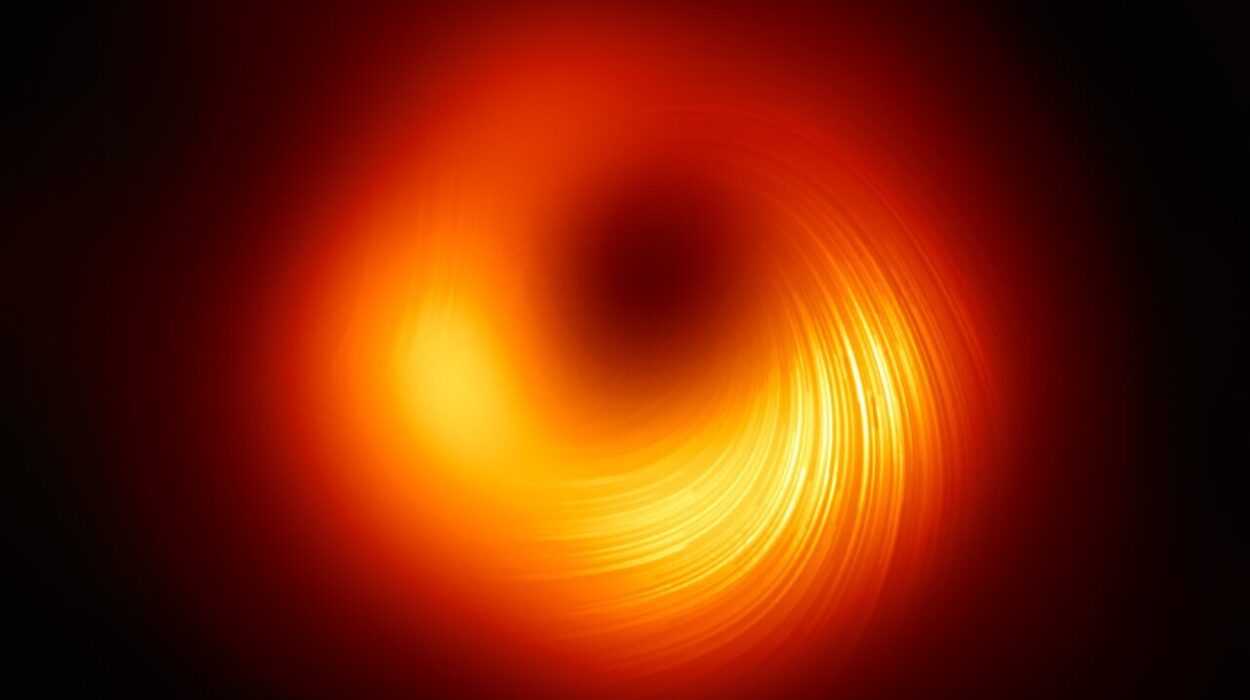

- Stars above 260 solar masses may have collapsed directly into black holes without an explosive finale, potentially forming the seeds for the supermassive black holes we find at the centers of galaxies today.

The End of Darkness—Cosmic Reionization

Lighting Up the Universe

The ultraviolet radiation emitted by Population III stars had a critical role in transforming the universe. Their intense energy ionized the neutral hydrogen gas that filled space, breaking atoms apart into protons and electrons.

This process is called cosmic reionization. It marked the end of the Cosmic Dark Ages and the beginning of a universe that was bright and transparent.

Reionization was not instantaneous. It unfolded over hundreds of millions of years, as the first stars, and later the first galaxies, flooded the universe with radiation. The ionized bubbles around stars and galaxies grew larger and larger until they overlapped, turning the universe from opaque to transparent.

By about a billion years after the Big Bang, most of the intergalactic medium had been reionized. The universe was no longer dark—it was filled with light.

Seeding the Cosmos

The First Heavy Elements

The death of Population III stars seeded the cosmos with the first heavy elements, or “metals” in astronomical terms. These elements were dispersed into the interstellar medium by supernova explosions.

Before this, the universe had been a simple place: hydrogen, helium, and a touch of lithium. Afterward, it became far more complex. Elements like carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, iron, and many others became available for the formation of new stars, planets, and eventually life.

These metals cooled the gas clouds more efficiently, allowing subsequent generations of stars—Population II stars—to form. These stars were smaller and longer-lived, more like the stars we see today.

The Seeds of Galaxies and Black Holes

Some Population III stars collapsed into black holes. These black holes could have acted as the seeds for the growth of supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

As gas continued to fall into these black holes, they grew larger and more powerful, eventually becoming quasars, some of the brightest and most energetic objects in the universe.

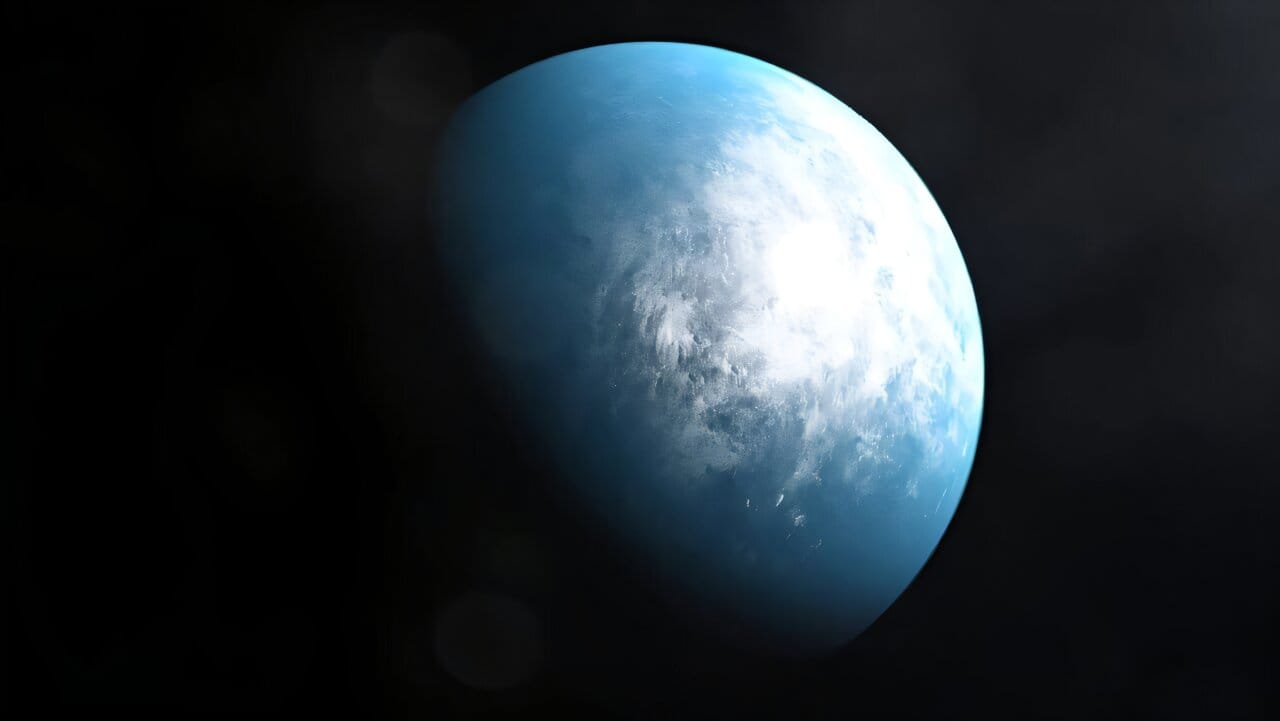

Meanwhile, the galaxies that formed around dark matter halos, enriched by the metals from Population III supernovae, began to take shape. Stars, dust, gas, and dark matter came together to form the first galaxies—structures that would continue to evolve into the grand spiral and elliptical galaxies we see today.

Hunting the Ghosts of the First Stars

Have We Seen Population III Stars?

Despite their importance, Population III stars remain elusive. They lived and died long ago, and no direct observations have yet revealed them.

Astronomers search for their fingerprints in several ways:

- Metal-Poor Stars: Some ancient stars in the Milky Way halo are incredibly metal-poor, suggesting they formed from gas enriched by just one or a few Population III supernovae. Studying these stars helps scientists infer the properties of the first stars.

- Distant Galaxies: Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are peering deep into the early universe, searching for galaxies that might contain Population III stars or their immediate descendants.

- Supernovae and Gamma-Ray Bursts: Powerful explosions in the early universe may be the deaths of Population III stars. Observing these events could provide clues about these ancient behemoths.

The Future of Discovery

The search for Population III stars is one of the most exciting frontiers in astronomy. With next-generation observatories, astronomers hope to uncover direct evidence of the first stars and their role in shaping the universe.

JWST, in particular, has the power to peer back over 13 billion years, potentially revealing the light from the earliest galaxies and stars. Future telescopes, such as the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), will offer even greater precision.

Conclusion: The Dawn That Shaped Everything

The story of Population III stars is the story of our cosmic origins. These first stars brought light to a dark universe. They forged the elements that make up our bodies, our planet, and everything we see around us.

Though they lived fast and died young, their legacy endures. Every star, every galaxy, and every planet owes its existence to them. Without Population III stars, the universe would be a cold, dark, and sterile place.

As we search for the light of these ancient stars, we are also searching for the beginnings of everything we know. The dawn of light was the first step on a journey that led to us—beings capable of looking back across time and wondering where it all began.

And in that wonder, we find our connection to the first stars, the luminous titans who turned darkness into dawn.