For centuries, the windswept grasslands of Mongolia have held tight to their secrets. Among them lies Bayanbulag, an archaeological site that—until recently—was little more than a footnote in the broader story of the epic clashes between the Han Empire and the Xiongnu nomads. Now, cutting-edge bioarchaeological research, spearheaded by a team from Jilin University in China, is prying open a window into this tumultuous period of ancient history. Their findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, offer compelling evidence about who fought, who died, and how imperial ambitions shaped lives on the brutal frontiers of the early Iron Age.

This new study brings the bones of long-dead soldiers back into the historical conversation—giving voice to men whose stories were never told.

An Ancient Conflict Revisited: The Han-Xiongnu War

To understand the significance of the discoveries at Bayanbulag, we need to revisit the Han-Xiongnu War—one of the most dramatic military struggles in early Chinese history. Beginning in the 2nd century BC, the Han dynasty and the Xiongnu confederation clashed repeatedly in a protracted and often brutal conflict. For the Han Empire, these wars were a desperate attempt to control and pacify their volatile northern frontier. For the Xiongnu, nomadic horse lords who dominated the Mongolian steppes, it was a fight for survival and supremacy.

Ancient Chinese records detail elaborate military campaigns, heroic generals, and conquests won. But these accounts come almost exclusively from Han scribes—propagandists, in effect—who painted their empire as righteous and orderly, while the Xiongnu were cast as barbarian adversaries. What those ancient histories rarely, if ever, mention are the individual soldiers who manned the lonely outposts and met their deaths far from home. That is, until now.

Bayanbulag: A Fortified Frontier Outpost

Located deep in Mongolia, Bayanbulag was first identified as an archaeological site in 1957. But for decades, the ruins remained unexplored, their secrets untouched by trowel or theory. It wasn’t until 2009 that systematic excavations began to peel back the layers of time.

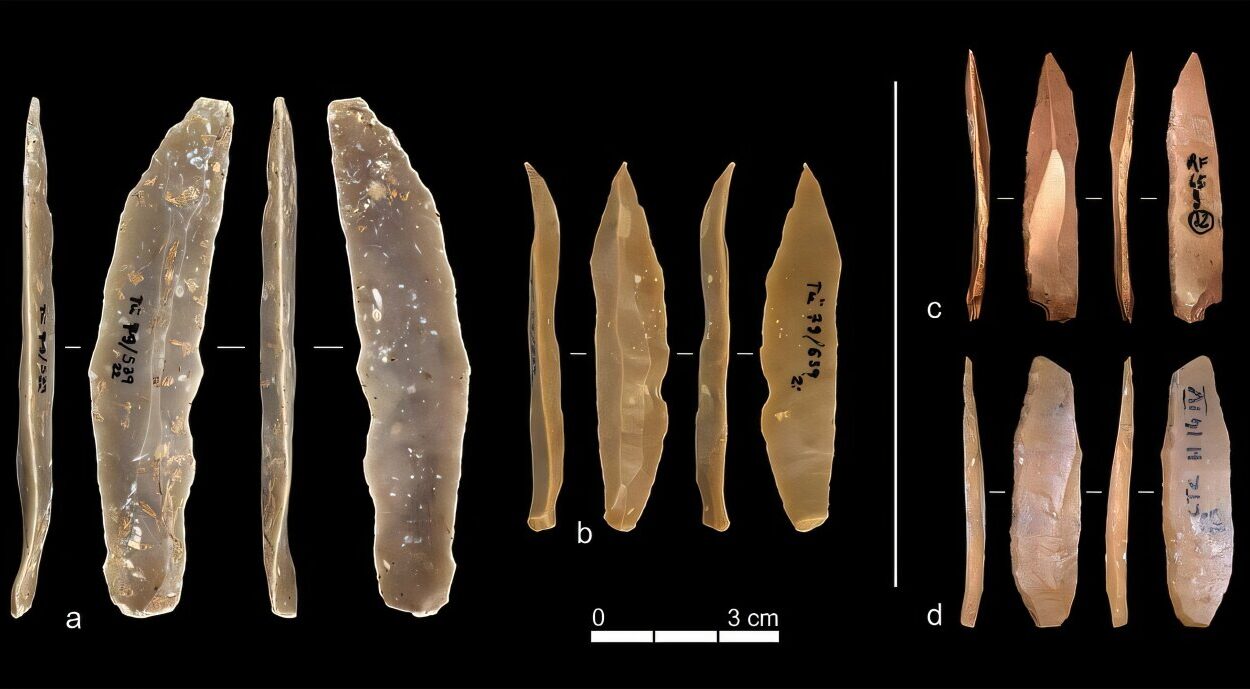

Archaeologists uncovered what appeared to be the remnants of a fortified settlement. Iron tools, pottery, bronze crossbow mechanisms, iron halberds, coins, and an official Han clay seal all pointed to a structured military presence. This wasn’t just a remote camp—it was a garrisoned outpost. Some scholars believe this was the elusive Shouxiangcheng (“Fortification for Receiving Surrender”), established by the Han around 104 BC as a foothold in Xiongnu territory.

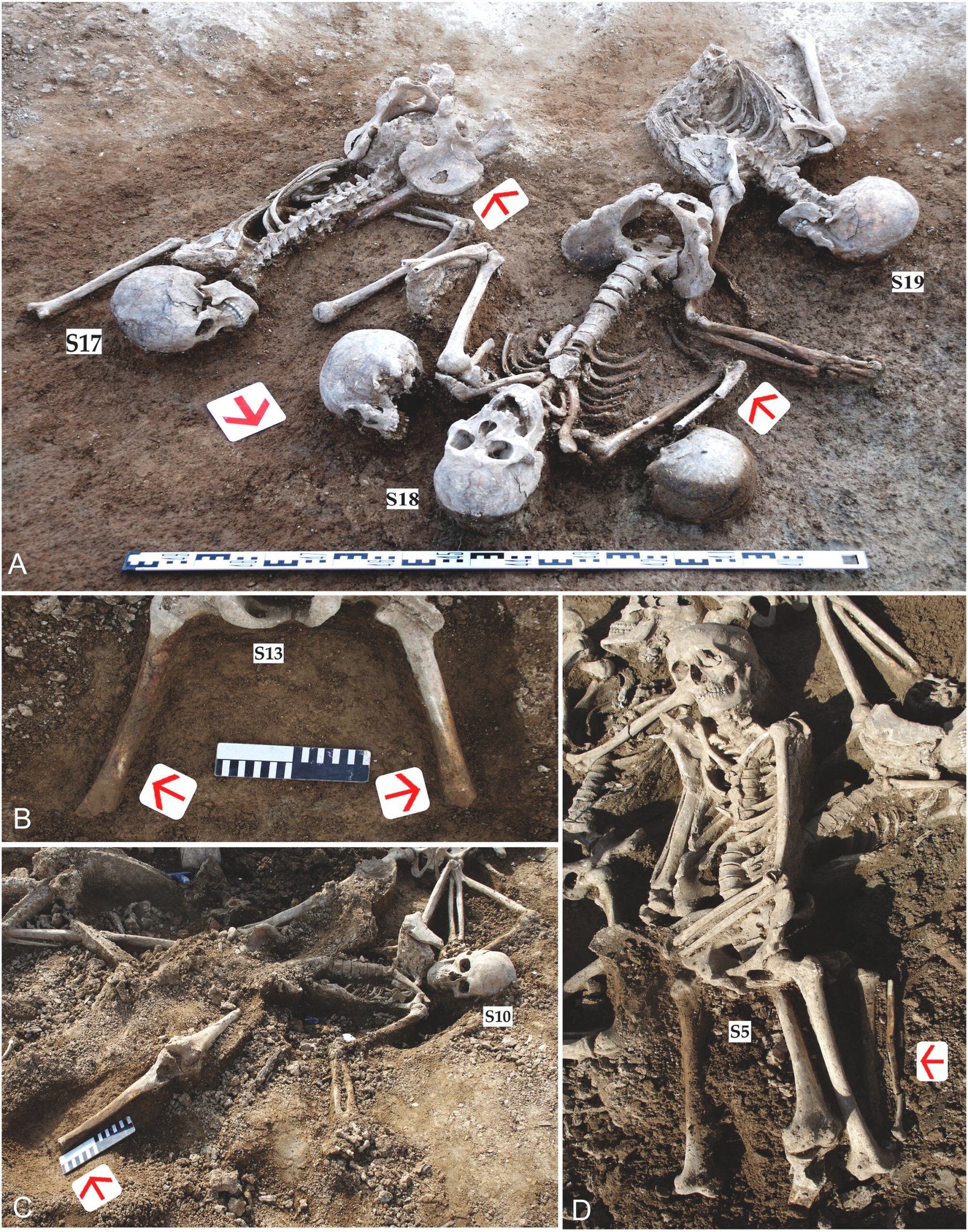

But alongside the implements of bureaucracy and defense, a much grimmer discovery emerged: a mass grave filled with the dismembered skeletons of more than 20 individuals, hastily buried in a pit at the site’s edge.

The Human Cost: A Burial Pit of Soldiers and Violence

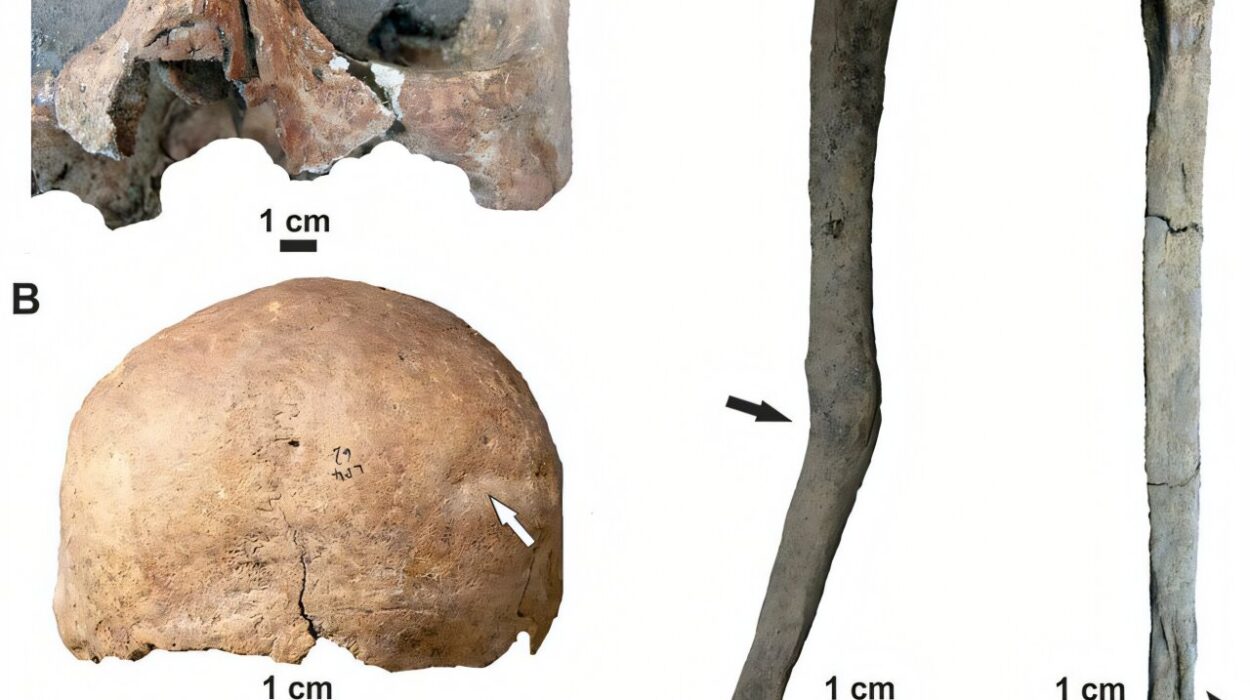

The bones in that burial pit told a harrowing story. Early osteological studies revealed evidence of interpersonal violence: shattered skulls, severed limbs, and indications of execution. Some skeletons were found in kneeling positions, bound and possibly beheaded—grisly echoes of a ritualized punishment or battlefield discipline. The bodies had been treated with striking brutality.

But who were they? Historical texts are silent on this mass death event at Bayanbulag. Were these men Xiongnu warriors captured and executed by Han forces? Were they Han soldiers who mutinied and paid with their lives? Or perhaps they were simply the victims of the relentless, shifting tides of frontier warfare?

These were the lingering mysteries—until science stepped in.

Cracking the Genetic Code of Ancient Warriors

The research team from Jilin University turned to the latest bioarchaeological techniques to answer the centuries-old question of identity. By extracting ancient DNA from 14 tooth samples, they were able to sequence entire genomes, tracing the ancestry of these long-dead soldiers.

The results were clear and striking: all 14 individuals were male, and of those, 11 had sufficient DNA coverage to confirm their genetic affiliations. These men shared a common ancestry with ancient and modern Han Chinese populations from North China. Specific Y-chromosome haplogroups—O2a2b1a1a-F8, O2a2b1a2-F114, and Q1a1a1a-M120—linked them directly to populations in the Yellow River Basin, a cradle of early Chinese civilization.

Further analysis of mitochondrial DNA revealed a diversity of maternal lineages, mirroring patterns still found in modern Han populations. This genetic mosaic suggests that the Han Empire’s recruitment efforts drew men from a wide range of communities in North China, forging them into an army dispatched to the distant Mongolian frontier.

Following the Isotopic Breadcrumbs

DNA wasn’t the only line of evidence. The team also analyzed strontium isotopes in tooth enamel. These isotopes provide a kind of geological signature, revealing where a person grew up based on the water and soil chemistry of their home region.

The results again pointed south of Mongolia. The 87Sr/86Sr values closely matched isotopic signatures from North China, specifically regions like the Ordos Plateau and the Central Plains. These men were not native Mongolian steppe dwellers; they were outsiders, born and raised far to the south, conscripted into the Han military machine.

Stable carbon isotope analysis painted an equally telling picture of their lives. Their diets consisted primarily of millet and wheat—common staples of settled agricultural communities in North China—rather than the meat- and dairy-heavy diet of the Xiongnu pastoralists. These men were farmers before they were soldiers.

A Glimpse into Han Military Strategy

What emerges from this web of genetic and isotopic data is a vivid picture of Han frontier strategy. Bayanbulag was likely a fortified garrison designed to enforce Han authority along the borderlands rather than a permanent attempt to colonize Xiongnu territory. The men stationed there were farmers conscripted into military service, posted far from home to a volatile and dangerous frontier.

But their fate remains a haunting mystery. Did they die defending the fort from a Xiongnu assault? Were they executed by their own commanders for desertion, rebellion, or failure in battle? The ritualistic treatment of some bodies—kneeling skeletons, evidence of decapitation—suggests that these men may have died not in the chaos of combat, but in the cold deliberation of punishment or ritual execution.

Rewriting the Story of the Han-Xiongnu War

The discoveries at Bayanbulag challenge and enrich our understanding of the Han-Xiongnu War. Ancient texts give us the top-down view: emperors, generals, alliances, and battles. But at Bayanbulag, bioarchaeology gives us the bottom-up perspective—the lives and deaths of ordinary soldiers, conscripts who left their farms in the Yellow River heartland and never returned.

These were not nameless pawns; they were men with families, lineages, and stories now partially recovered through science. Their teeth, bones, and genes speak across millennia, offering a poignant reminder that the costs of empire are paid in human lives.

The Frontier’s Silent Witnesses

Today, Bayanbulag remains a silent witness to a turbulent age. But thanks to advances in ancient DNA analysis, isotopic chemistry, and archaeological science, we are beginning to hear the echoes of its past. This research not only provides answers to who these men were but also highlights the power of interdisciplinary science to reconstruct histories left out of the written record.

The Han-Xiongnu War was not just an epic clash of civilizations; it was also a struggle fought by individuals whose identities and fates are only now being understood. And as new technologies continue to unlock the secrets of ancient graves, more stories are sure to emerge from the shadows of history.

Reference: Pengcheng Ma et al, Bioarchaeological perspectives on the ancient Han-Xiongnu war: Insights from the Iron Age site of Bayanbulag, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106184