In 1977, humanity launched its voice into the vast and silent ocean of space. Not a transmission, not a blinking beacon—but something tangible. A time capsule. A message in a bottle. A golden disc that would sail beyond the sun’s gravitational reach, carrying whispers of life on Earth into the deep black. It was called The Voyager Golden Record, and it was perhaps the most ambitious love letter ever written by our species: a greeting card to the stars, bearing the hopes, dreams, sounds, and soul of our small, blue world.

What makes the Golden Record extraordinary isn’t just its scientific intention. It’s the fact that it represents an act of cosmic outreach, a statement of self in the hope that somewhere, someday, someone might listen. It is humanity’s signature scrawled across the galactic void.

This is the story of the Golden Record—its conception, creation, and launch aboard Voyager 1 and 2. It is the story of our greatest message to the unknown.

The Era of Voyager: A Leap Beyond Earth

The 1970s were an era of wonder. Space exploration was no longer the stuff of science fiction but an unfolding reality. The Apollo moon landings had captured the imagination of the world, and NASA was ready for its next great endeavor: the exploration of the outer planets.

The Voyager program was born of this ambition. Two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, were designed to explore the massive outer planets of our solar system: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. These robotic explorers would be humanity’s first emissaries to worlds that had, until then, been only distant points of light in our night sky.

But there was a twist. Scientists realized that these spacecraft, once their planetary missions were complete, wouldn’t just stop. They would keep going. Out beyond Pluto. Beyond the heliopause, the boundary where the Sun’s influence fades. They would sail on into interstellar space.

And someone had an idea: what if we sent something with them?

Something that would outlast us all.

The Birth of the Golden Record

The idea wasn’t entirely new. In 1972 and 1973, NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 missions had carried small metal plaques engraved with diagrams—a basic introduction to Earth and its location in the galaxy, along with figures of a man and a woman. These plaques, designed by Carl Sagan and Frank Drake, were humanity’s first deliberate attempt to communicate with extraterrestrial intelligence.

But the Voyager spacecraft presented a bigger opportunity. They could carry not just diagrams, but sounds. Images. Music. A message richer, deeper, and more profound than any previous effort.

In 1977, NASA appointed Carl Sagan—astronomer, astrophysicist, and one of the world’s great science communicators—to lead the committee responsible for creating this message. Sagan, along with a small team of scientists, artists, writers, and engineers, had less than a year to craft what would become the Golden Record.

What do you say when you have the chance to introduce yourself to the cosmos?

What Is the Golden Record?

Physically, the Voyager Golden Record is a 12-inch gold-plated copper phonograph disc. It is enclosed in an aluminum case, along with a cartridge and a needle—just in case the beings who find it need help figuring out how to play it. On the cover are etched instructions, as well as a pulsar map that indicates Earth’s position in the galaxy.

But it’s what’s on the record that matters. A compilation of sounds, music, greetings, and images, all intended to represent life on Earth. In essence, it’s an interstellar mixtape—one curated with care, love, and a profound sense of purpose.

The contents were encoded in analog, with images and audio included in much the same way a traditional vinyl record stores music.

If a civilization ever finds one of the Voyagers, and if they are curious and advanced enough to decipher it, they will hear the voices of humanity. They will see our faces. They will listen to our music. They will glimpse Earth as it was, through our eyes.

The Sounds of Earth: A Sonic Snapshot of a World

The Golden Record begins with a collection of natural sounds—a sensory montage intended to give the listener an impression of Earth’s environment and life forms.

You’ll hear the crackle of fire, the rumble of thunder, the song of birds, the call of whales, the rustle of wind, and the murmur of a mother cradling her infant. It’s as if the planet itself is alive, breathing its sounds into the emptiness of space.

But there’s more. Included are greetings in 55 languages, spoken by men, women, and children. Each offers a brief salutation: “Hello,” “Peace,” or “Welcome.” Some are formal; others are playful or poetic. The greeting in Amoy (a dialect of Chinese) cheerfully says, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” There’s something hauntingly hopeful in these words: a human voice speaking into the unknown, expecting no reply but hoping all the same.

There’s also a message from the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim, expressing the collective hope for peace and friendship. And, tucked into the audio, is a recording of the brainwaves of Ann Druyan—creative director of the Golden Record project and, later, Carl Sagan’s wife. Her brain activity was recorded while she meditated on humanity’s greatest hopes, fears, and the love she felt for Sagan. Her thoughts, in a sense, are on that record too.

And then there’s music.

The Music of Earth: A Universal Language

How do you pick a soundtrack for a planet?

This was one of the most daunting tasks for Sagan’s team. Music, after all, is not only an art form but an expression of culture, history, and emotion. It transcends language and geography, making it a perfect ambassador.

The Golden Record includes 90 minutes of music, spanning cultures and centuries. Among the selections are:

- Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2—an intricate and joyful piece of Baroque music.

- Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and the Cavatina from String Quartet No. 13—melancholy and sublime.

- Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, powerful and primal.

- Traditional songs from China, Japan, and Peru.

- A Navajo night chant.

- A wedding song from India.

- The sound of an Australian Aboriginal songman.

- And even Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”—a high-energy slice of American rock and roll.

The inclusion of Chuck Berry was controversial at the time. Some thought rock music inappropriate for an interstellar greeting. But Carl Sagan famously defended its inclusion, reportedly saying, “There are a lot of teenagers on Earth.”

The music reflects not just who we are, but who we aspire to be: a species united in diversity, creating beauty in many forms.

The Images: Portraits of Life on Earth

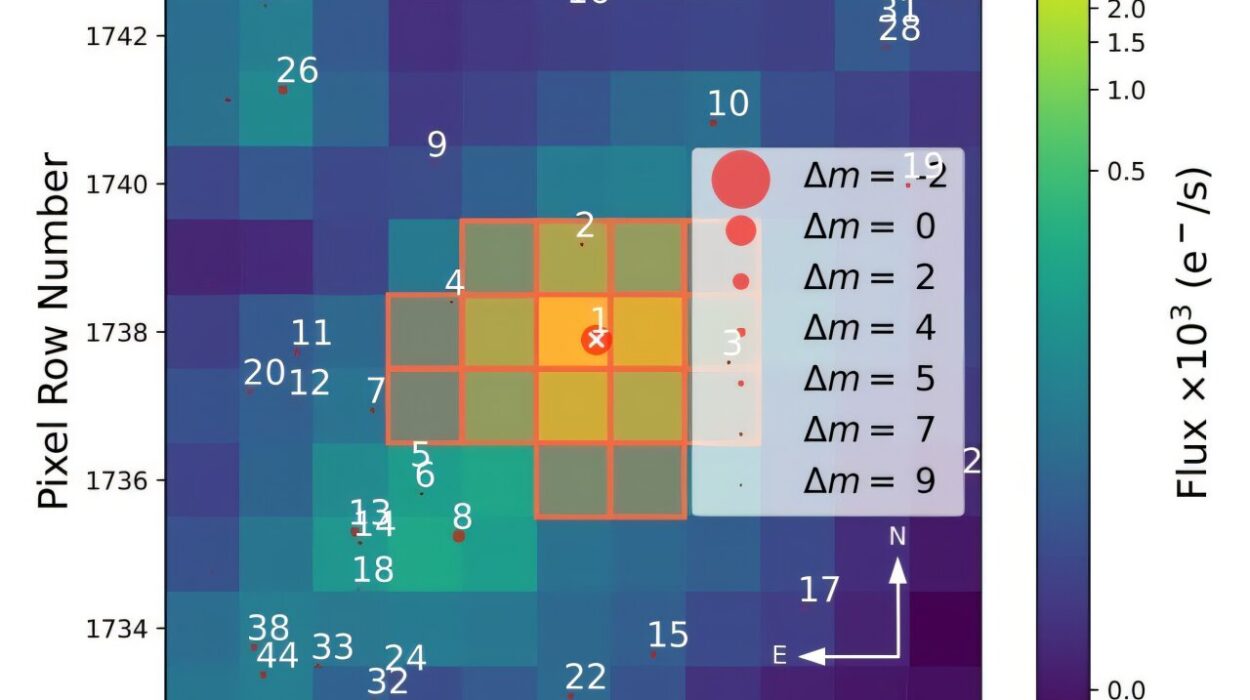

The Golden Record also contains 116 images, encoded as analog signals. These photographs and diagrams were chosen to give extraterrestrial viewers a sense of Earth’s geography, biology, and culture.

There are images of human anatomy and reproduction, of cities and farmlands, of technological achievements like airplanes and spacecraft. There are photos of people eating, laughing, and learning. There are animals—frogs, elephants, and dolphins—and plants, from towering trees to delicate flowers.

One striking photo shows a father lifting his child into the air. Another depicts a page from a book, a symbol of learning and communication. There’s even an X-ray of a human hand.

Accompanying these images are scientific diagrams: mathematical definitions, the structure of DNA, and the solar system. These were intended to communicate humanity’s understanding of science and our place in the cosmos.

And, of course, there is a photo of Earth itself: a blue and white marble hanging in the blackness of space.

Ann Druyan’s Love Story: A Personal Note on the Record

One of the most beautiful stories about the Golden Record concerns Ann Druyan. While working on the project, she and Carl Sagan fell in love. Their relationship was swift and intense, and it unfolded in tandem with the creation of the record.

At one point, Druyan underwent a brainwave recording session. Electrodes were attached to her head to capture the patterns of her neural activity. As the sensors recorded, she meditated on the essence of humanity: its achievements, hopes, and struggles. But she also thought about her love for Sagan—a new, overwhelming feeling.

Those thoughts, encoded in her brainwaves, are now traveling through space aboard Voyager. Somewhere out there, her love story drifts among the stars.

Voyager’s Journey: Where Are They Now?

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched in 1977. Over the years, they returned breathtaking images and data from the outer planets, revolutionizing our understanding of the solar system.

Today, both spacecraft are far beyond Pluto. In 2012, Voyager 1 entered interstellar space, followed by Voyager 2 in 2018. They are the farthest human-made objects from Earth, each carrying a Golden Record—a message from Earth, floating in the infinite night.

At their current speeds, they will take tens of thousands of years just to cross the distance to the nearest star systems. The odds that any alien civilization will find them are infinitesimal. But that was never the point.

Why We Sent the Golden Record: Hope, Curiosity, and Wonder

The Golden Record wasn’t about likelihood. It was about possibility. It was about sending a piece of ourselves into the universe as an act of faith—faith that we are not alone, and faith that who we are matters.

As Carl Sagan put it:

“The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

The Golden Record is a testament to our curiosity and our longing for connection. It reflects our recognition that we are a small species on a tiny world, but that we have the ability to reach out across time and space with a gesture of peace.

It is, in its essence, a gift. Not just to other civilizations, but to ourselves.

Legacy: Humanity’s Calling Card

The Golden Record has inspired generations. Musicians, artists, filmmakers, and writers have drawn upon its story as a metaphor for human resilience and imagination.

In 2017, on the 40th anniversary of the Voyager launches, a special edition of the Golden Record was released on vinyl for Earthbound listeners. For the first time, people could hear and hold a copy of the message meant for the stars.

And as we look to the future—toward missions to Mars, to Europa, and even beyond the solar system—the Golden Record remains a symbol of who we are at our best: curious, hopeful, creative, and kind.

Conclusion: A Message That Will Outlast Us All

The Golden Record may one day be all that is left of humanity. Long after our civilizations have faded and our cities have crumbled, Voyager 1 and 2 will still be sailing among the stars. Their tiny golden discs will carry our songs, our greetings, our heartbeat.

Even if no one ever finds them, the act of sending them was enough.

We placed a gift in the cosmic ocean, not knowing if it would ever be received. And in doing so, we declared to the universe: We were here.

And maybe, just maybe, someone—somewhere—will listen.