When we think about the dazzling palette of colors in the animal kingdom, our minds often turn to birds of paradise flaunting iridescent feathers, or butterflies sporting kaleidoscopic wings. Even flowers get credit for flaunting brilliant hues to lure pollinators. But what if the most vibrant and complex color stories are happening just beyond what our eyes can perceive?

That’s exactly what a recent University of Michigan study suggests. Diving deep into a hidden world of color invisible to the human eye, researchers have uncovered how snakes—long thought of as relatively cryptic or even colorless—are sporting vivid ultraviolet (UV) coloration. This discovery doesn’t just add a new dimension to how we think about snakes; it opens the door to an entirely new frontier in the study of animal coloration.

And it all begins with a simple, yet powerful question: What colors exist beyond human sight, and why do they matter?

Color Beyond the Human Eye

For centuries, scientists have been captivated by the visual spectacle of nature. But there’s a catch: nearly all of this research has been filtered through the limitations of human vision, which detects just a narrow slice of the light spectrum. Humans can’t see ultraviolet light, but many animals can, from insects and birds to reptiles. In fact, the animal kingdom is practically teeming with UV vision and, as this study demonstrates, UV-based communication and camouflage.

“A lot of UV color work is done in systems that we consider traditionally bright and colorful, like birds, flowers and butterflies,” explains Hayley Crowell, lead author of the study and doctoral student in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan. “But color research is really biased by human perception. We’ve ignored entire groups of animals that might be using color in ways we can’t even imagine.”

Enter the snake.

The Study: A Deeper Look at Snakes in UV

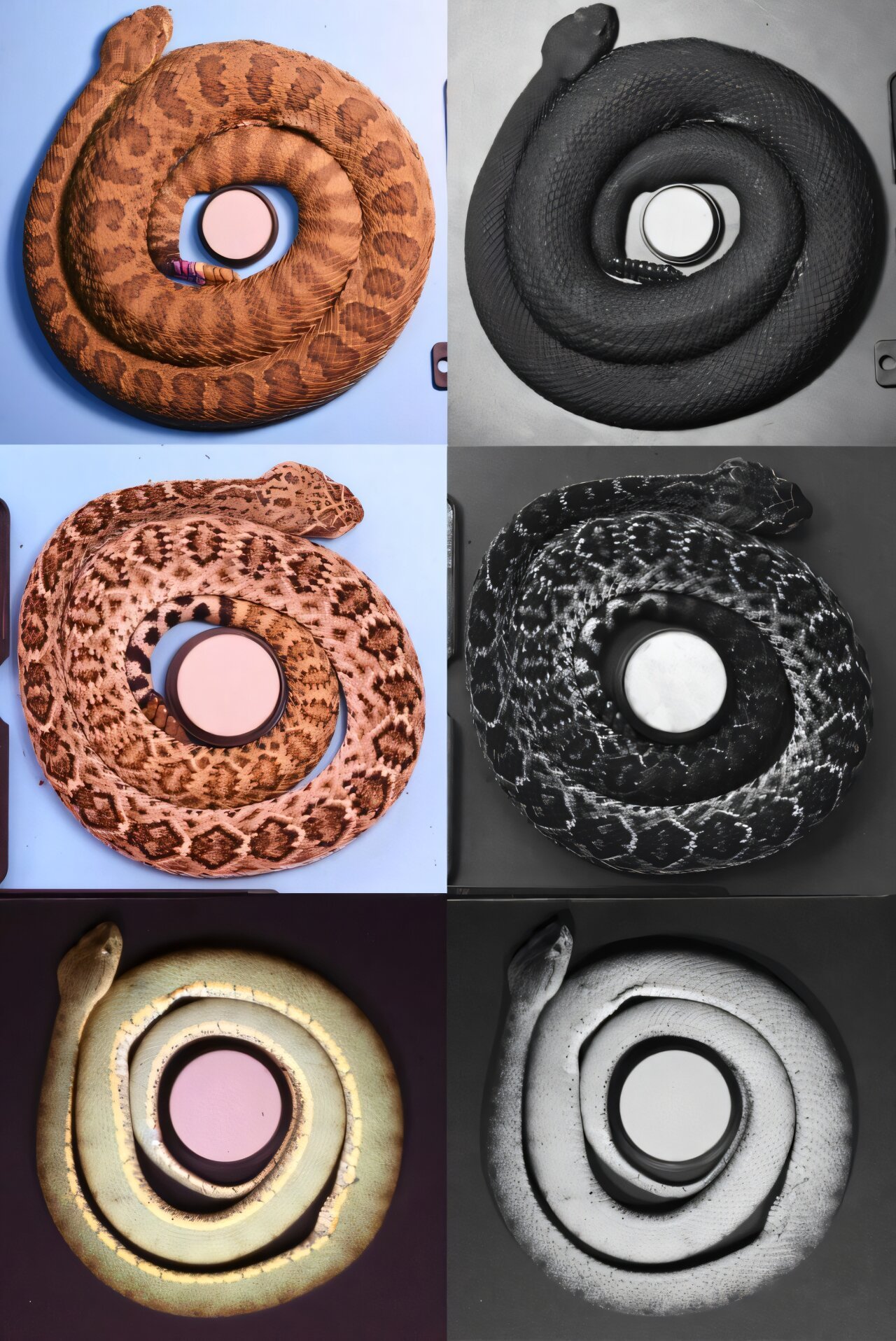

Crowell and her colleagues examined 110 species of snakes, ranging from the deserts of Colorado to the rainforests of Peru. Using specialized cameras equipped with UV-sensitive lenses and filters, they photographed these animals under controlled lighting conditions. Unlike UV fluorescence, which often requires black lights to be seen (think of those glowing scorpions under UV lamps), the study focused on true UV reflectance—colors that are visible to animals with UV vision, but completely hidden to us.

The researchers weren’t just interested in whether snakes reflected UV light. They wanted to understand how and why UV coloration evolved in these reptiles. What ecological factors promoted its development? Was UV color more common in certain environments or life stages? Did it vary between males and females, as it often does in other animals where flashy colors are used to attract mates?

The answers were as complex as they were surprising.

Snakes and UV Camouflage: Hiding in Plain Sight

One of the study’s most striking findings was the widespread presence of UV coloration across the snake tree of life. But this wasn’t just random decoration. The researchers discovered that UV color in snakes is tightly linked to ecology—specifically, where they live and how they avoid predators.

Arboreal snakes, those that live in trees, were some of the most UV-reflective species. Many of these snakes are nocturnal hunters, active under the cover of darkness, but they rest during the day. During daylight hours, these snakes are vulnerable to predators like birds, many of which have excellent UV vision. Crowell believes that by reflecting UV light in a way that mimics their environment—think UV-reflective lichens, mosses, and leaves—these snakes can camouflage themselves against the background of the forest canopy.

“The idea is that these snakes are hiding in a UV-rich environment,” Crowell says. “By reflecting UV light in the same way their environment does, they essentially blend in and become much harder for predators to spot.”

It’s a brilliant strategy: stay invisible to birds by matching the ambient UV reflectance of your surroundings. And it suggests that snakes may have evolved these UV traits not to stand out, but to disappear.

Breaking the Mating Mold

One of the more surprising outcomes of the study was what the researchers didn’t find—sexual dimorphism in UV coloration. In many animals, especially reptiles like lizards, males and females look different, with males often displaying bright colors to attract mates. Yet in the snakes studied, males and females showed no consistent differences in UV reflectance.

“Because reproduction drives UV color evolution in so many other species, the lack of sexual differences in snakes was a surprise,” notes Alison Davis Rabosky, associate professor at the University of Michigan and co-author of the study.

This suggests that, for snakes, UV coloration isn’t about attracting a partner. Instead, it’s about survival—avoiding detection by predators rather than standing out to potential mates. That makes sense, says Rabosky, because snakes rely heavily on other senses, like pheromones, to find mates. Visual cues may simply not play as large a role in their reproductive lives as they do in other animals.

John David Curlis, a postdoctoral fellow and another co-author, highlights the difference between snakes and their close relatives, lizards. “Sexual dimorphism is incredibly common in lizards, with males often displaying bright colors and large ornaments,” he explains. “The fact that snake colors didn’t differ between the sexes suggests that sexual selection plays less of a role in snake color evolution.”

But this isn’t the whole story.

A Puzzle with Many Pieces: Individual Variation in UV

While snakes didn’t show sexual differences in UV color, they did show something equally intriguing—huge variation within species. In some cases, two snakes of the same species, collected from the same place, and of the same sex, reflected UV light in dramatically different ways. One might blaze with UV reflectance on its back, while its counterpart was completely dull.

Even within a single genus of snakes, some species were among the most UV-reflective in the study, while others barely reflected UV at all. Vipers, in particular, showed a huge range of UV coloration. The team also found that juveniles often had more UV color than adults, possibly because young snakes are more vulnerable to predators and need better camouflage.

“This kind of individual variation is really fascinating,” says Hannah Weller, a co-author and postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Helsinki. “It tells us that UV coloration isn’t a simple trait with a one-size-fits-all explanation. It’s highly dynamic and variable, even within a single species.”

This complexity opens new avenues for research. Are snakes able to change their UV reflectance over time? Does diet, health, or environment influence their UV color? And could these differences have implications for how snakes interact with predators, prey, or even each other?

What We’ve Been Missing: A Call for Broader Vision

For decades, color research in animals has been heavily skewed toward species and systems that are, to human eyes, bright and flashy. But Crowell and her team argue that this bias has caused us to overlook entire groups of animals—snakes included—that are using color in fascinating, if invisible, ways.

“I think we scientists have simply overlooked a lot of UV coloration in cryptically colored species, especially in insects,” Rabosky says. “They are the next frontier.”

This study challenges us to expand our vision, both literally and metaphorically. Animals don’t perceive the world the way we do. They see things we can’t, respond to signals we’re blind to, and evolve traits that are invisible to human observers but crucial for survival in their world.

The implications go beyond snakes. If UV color plays such a crucial role in the lives of animals we thought were drab and colorless, what else have we missed? What secrets are hiding in the scales of lizards, the feathers of birds, or the wings of moths?

A New Frontier in Color Science

As Crowell and her colleagues emphasize, the next step is to broaden our studies of color beyond the confines of human perception. That means investing in more research on UV coloration in other animals, especially those considered “uncolorful.” It also means rethinking how we describe and categorize animal traits.

“We need to stop thinking of animals in terms of how they look to us,” Crowell says. “Instead, we should try to understand how they look to each other—and to the predators and prey they interact with.”

The University of Michigan study is a powerful reminder of how much more there is to learn. Snakes, once thought to be cryptic and colorless, have shown us that nature’s palette is far richer and more complex than we ever imagined. And it’s only the beginning.

As we continue to push the boundaries of science and technology, we’re starting to see the world through new eyes. With every discovery, we peel back another layer of the natural world’s mysteries—and realize how much we’ve yet to uncover.

Key Takeaways:

- Snakes reflect ultraviolet (UV) light in ways invisible to humans but visible to many predators and prey.

- UV coloration in snakes is widespread and tied closely to ecology, particularly in arboreal, nocturnal species that need camouflage from UV-sighted predators like birds.

- Unlike many animals, snakes show no sexual dimorphism in UV coloration, suggesting UV color isn’t driven by mate selection.

- There’s huge individual variation in UV coloration within snake species, raising new questions about how UV reflectance develops and functions.

- The study calls for a broader, less human-centric approach to studying color in nature.

Nature’s most stunning colors might be the ones we’ve never seen—until now.

Reference: Hayley L. Crowell et al, Ecological drivers of ultraviolet colour evolution in snakes, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49506-4