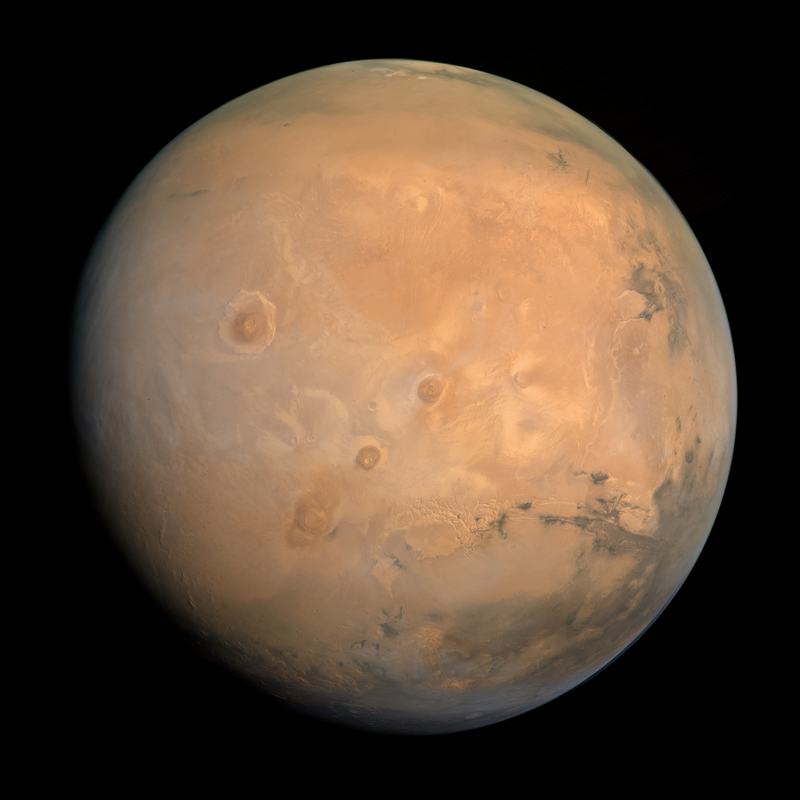

For more than three billion years, Mars has whispered secrets about its watery past. Once, rivers carved winding channels through its ancient terrain. Vast lakes may have dotted its basins, and perhaps even oceans lapped at its shorelines. But then, something changed. The planet’s thin atmosphere faded, and along with it, the era of persistent liquid water on the Martian surface came to an end. What happened to all that water? Did it escape into space, freeze beneath the ground, or become trapped in the very rocks that shape the planet’s crust? This mystery has intrigued scientists for decades, and a new debate has reignited the search for answers.

At the forefront of this discussion is Bruce Jakosky, a Senior Research Scientist at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at the University of Colorado Boulder. Jakosky, who led NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) mission, has spent much of his career studying Mars’s atmospheric history and its elusive water. Recently, Jakosky weighed in on an exciting but controversial study published in August 2024 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The study, led by geophysicist Vashan Wright from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, made a bold claim: Mars may still harbor vast quantities of liquid water in its mid-crust, potentially as much as a global equivalent layer (GEL) of one to two kilometers thick if spread evenly across the planet’s surface.

But Jakosky isn’t convinced this is the only story the data tells.

The Ghost of Water Past

We already know that Mars wasn’t always the cold, arid world it is today. More than three billion years ago, conditions were dramatically different. Geological features captured by orbiters and rovers tell a tale of ancient river valleys, lake beds, and mineral deposits that could only have formed in the presence of water. Yet, as Mars lost much of its protective atmosphere, driven by solar wind stripping and lacking the shielding of a strong magnetic field, surface water became unstable. What remained of it was either frozen into polar caps, locked into subsurface ice, bound into minerals, or—possibly—escaped into space.

Missions like MAVEN have explored how Mars’s atmosphere thinned over time. But while we’ve gathered plenty of data about the planet’s surface and atmosphere, peering deep into its crust has been a far more difficult task.

That’s where NASA’s InSight mission comes in.

InSight: Listening to the Red Planet’s Heartbeat

Launched in 2018, the InSight lander was tasked with exploring the interior of Mars using seismic data. For nearly four years, it listened intently to marsquakes rumbling through the planet’s crust and mantle. This seismic information, along with gravity measurements and heat flow data, provided an unprecedented look into Mars’s interior structure. By 2022, however, the lander fell silent—its solar panels coated with thick Martian dust, cutting off its power supply.

Yet, the data InSight collected during its operation continue to fuel new theories. Wright’s team used InSight’s seismic and gravity data to model the composition of Mars’s mid-crust, specifically a region between 11.5 and 20 kilometers beneath the surface. Their conclusion? The best explanation for the observed data was fractured igneous rock saturated with liquid water. If true, this would be a monumental discovery, reshaping our understanding of Mars’s hydrological history.

They estimated that if this trapped water were to be spread evenly over the surface, it would amount to a GEL between one and two kilometers thick—an astonishing reservoir compared to Earth’s own global equivalent water layer of about 3.6 kilometers, nearly all of which exists in the oceans.

But science thrives on scrutiny, and Jakosky’s letter to PNAS reminds us why critical analysis is so essential in planetary exploration.

Challenging the Conclusion: Jakosky’s Alternative View

Bruce Jakosky isn’t disputing that Wright and his colleagues conducted a careful and thorough study. He acknowledges the team’s modeling approach was both “reasonable and appropriate.” However, he argues that the data don’t necessarily lead to a single conclusion. While Wright’s models suggest a water-saturated crust as a plausible scenario, Jakosky points out that other possibilities fit the data just as well.

Jakosky’s reanalysis focuses on how the rock’s pore space—the tiny voids between grains or within fractures—might be distributed. Could these pores be empty? Could they instead be filled with solid ice rather than liquid water? Both scenarios could produce similar seismic and gravity signatures to those observed by InSight. He concludes that while the upper estimate of a GEL up to two kilometers is plausible, the lower bound could be zero.

In other words, Mars’s crust might hold significant quantities of liquid water—or it might be bone dry in those regions. The data leave the door open to both possibilities.

Why It Matters: Water, Life, and Future Exploration

Why are these debates over buried Martian water so critical? Because they go to the heart of some of the biggest questions humanity asks about the Red Planet.

Did life ever exist on Mars? Water is life’s essential ingredient. If liquid water persists in Mars’s subsurface today, it could provide an environment where life might have taken root—or could still exist in microbial forms, sheltered from the harsh conditions on the surface.

Can Mars support future human exploration? If significant water resources exist beneath the Martian crust, they could be a game changer for future crewed missions and potential colonization. Water isn’t just vital for drinking; it can be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel and breathable air, and it’s essential for growing food.

How did Mars evolve into the world we see today? Understanding the fate of its water helps unravel Mars’s climatic and geological history. Knowing whether water escaped into space, froze into the crust, or was chemically locked into minerals sheds light on the processes that transformed Mars from a once-habitable world into the desolate, frozen desert we see today.

What’s Next? The Need for More Data

Jakosky’s analysis highlights how much we still don’t know—and how much more data we need. The InSight mission was groundbreaking, but it was a single lander taking measurements from one location. To truly map Mars’s interior, we’ll need a network of seismometers and other geophysical tools scattered across the planet. More seismic stations would help triangulate marsquakes, revealing clearer images of Mars’s crust, mantle, and core.

Future missions might include deep drilling projects, capable of directly sampling crustal materials and determining whether they contain water, ice, or are completely dry. New orbiters with advanced radar systems could peer deep beneath the surface to map subsurface structures and ice deposits. Missions like ESA’s ExoMars, NASA’s Perseverance, and future robotic explorers will play critical roles in adding new pieces to the puzzle.

And if all goes according to plan, human explorers may one day follow. Their direct exploration could provide answers that are impossible to obtain through remote sensing alone.

The Martian Water Mystery: A Story Still Unfolding

For now, the fate of Mars’s water remains one of the solar system’s greatest mysteries. Scientists like Bruce Jakosky and Vashan Wright are piecing together a complex puzzle from limited data. Are we on the verge of confirming a hidden, planet-wide reservoir of water? Or will further investigation reveal a crust far drier than we hoped?

Either way, this debate fuels an exciting era of exploration. Every discovery about Mars, every new piece of data from missions past and future, brings us closer to answering age-old questions about life, habitability, and the evolution of planets in our solar system.

As Jakosky himself often emphasizes, Mars’s story is still being written. The next chapters will depend on humanity’s curiosity, ingenuity, and the relentless drive to explore new frontiers. Whether the Red Planet’s hidden waters will be found as trickles, pools, or ancient echoes, one thing is certain—our quest to understand Mars is only just beginning.

Reference: Bruce M. Jakosky, Results from the inSight Mars mission do not require a water-saturated mid crust, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2418978122