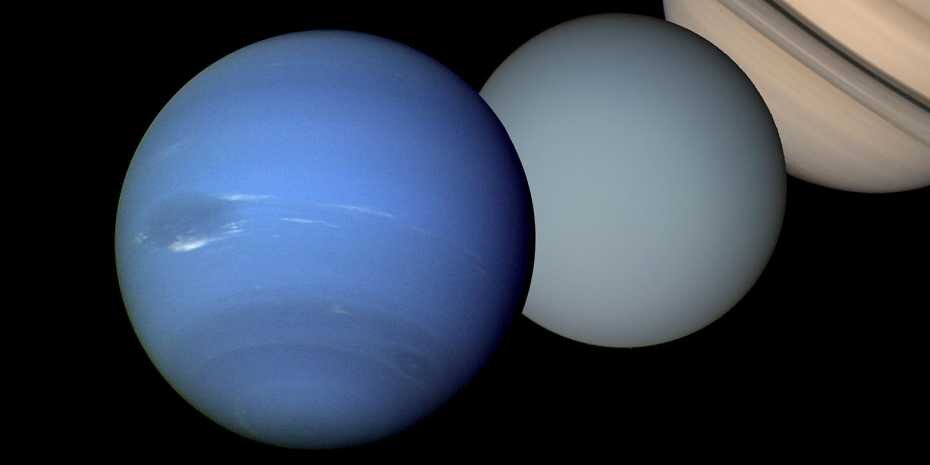

Beyond the warm, sunlit realm of the inner planets—past the rocky worlds of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and farther still beyond the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn—lies a realm of mystery. A distant, dimly lit expanse where sunlight struggles to reach, and temperatures plunge toward absolute zero. This is the domain of the ice giants: Uranus and Neptune. These two remote planets, often overshadowed by their more famous gas giant cousins, hold some of the greatest secrets of our solar system.

Unlike the bright bands of Jupiter or the stunning rings of Saturn, Uranus and Neptune have long kept their mysteries veiled in cold, blue clouds. Yet they are more than distant, frozen spheres adrift in the cosmic dark. They are dynamic worlds with turbulent atmospheres, raging storms, faint rings, strange magnetic fields, and a collection of moons that may hold clues to the origins of our solar system—and perhaps life itself.

But how much do we really know about Uranus and Neptune? And why do scientists consider them the key to understanding not just our own solar system, but exoplanets far beyond? To answer these questions, we must journey to the outer limits of our celestial neighborhood, where the ice giants spin in silent majesty.

The Discovery of Distant Worlds

For centuries, human beings gazed at the night sky and saw only five “wandering stars”—the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—moving among the fixed stars. These planets were known to ancient civilizations long before the invention of telescopes. They were bright, visible to the naked eye, and their movements across the heavens were tracked with care.

But Uranus and Neptune are different. They are too faint to be seen without optical aid. For much of human history, they were the hidden giants, lurking at the edge of visibility, their presence undetected.

Uranus: The First New Planet

In 1781, British astronomer Sir William Herschel was sweeping the skies with a telescope from his backyard in Bath, England, when he noticed an object that did not behave like a star. It was brighter, larger, and slowly moving across the sky. Herschel initially thought he had found a comet, but further observations revealed a planet—something unprecedented since ancient times.

Herschel wanted to name it Georgium Sidus (George’s Star) after King George III, but this didn’t sit well with astronomers outside Britain. Eventually, the planet was named Uranus, after the ancient Greek god of the sky, father of Saturn and grandfather of Jupiter. Uranus was the first planet discovered with a telescope, expanding the known boundaries of the solar system for the first time in human history.

Neptune: Predicted Before It Was Seen

Neptune’s discovery in 1846 is one of the most exciting detective stories in the history of astronomy. After Uranus was discovered and its orbit charted, astronomers noticed something odd. Uranus wasn’t where it was supposed to be. Its orbit was being perturbed by the gravitational pull of something unseen.

Two mathematicians, Urbain Le Verrier in France and John Couch Adams in England, independently calculated the position of a hypothetical planet influencing Uranus. Le Verrier sent his predictions to Johann Galle at the Berlin Observatory, who pointed his telescope at the predicted spot. There it was—Neptune, shining faintly in the dark sky, exactly where the math said it would be.

Unlike Uranus, Neptune was named for the Roman god of the sea, fitting for its deep blue appearance.

What Are Ice Giants, Anyway?

At first glance, Uranus and Neptune may seem like smaller versions of Jupiter and Saturn. They are gas giants, right? Not quite. While Jupiter and Saturn are composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, Uranus and Neptune are made of something quite different.

The Ice Giant Distinction

Uranus and Neptune are classified as ice giants, a term that distinguishes them from their larger gas giant cousins. The term “ice” in astronomy doesn’t just mean frozen water—it refers to volatile substances like water, ammonia, and methane, which condense into solid or liquid form at the frigid temperatures found in the outer solar system.

Both Uranus and Neptune are believed to have rocky cores, surrounded by thick mantles of icy materials, topped with hydrogen and helium atmospheres. Their interiors are not well understood, but scientists believe they contain exotic forms of water and ammonia, possibly in strange states like superionic ice—a form of ice that behaves like both a solid and a liquid and conducts electricity.

These compositional differences explain why Uranus and Neptune are denser, have different magnetic fields, and display unique atmospheric dynamics compared to Jupiter and Saturn.

Uranus—The Tilted Wonder

Uranus is a world turned on its side. With an axial tilt of 98 degrees, it essentially rolls around the Sun like a barrel rather than spinning upright like the other planets. This extreme tilt makes Uranus one of the most bizarre objects in the solar system.

Why Is Uranus Tilted?

Astronomers believe Uranus was knocked over by a massive collision with an Earth-sized object billions of years ago. This cataclysmic event could explain not only the planet’s tilt but also its unusual magnetic field and odd ring system.

As a result of its tilt, Uranus experiences extreme seasons. Each pole gets 42 years of continuous sunlight followed by 42 years of darkness. When Voyager 2 visited in 1986, Uranus’s south pole was pointed directly at the Sun.

The Pale Blue Planet

Uranus’s atmosphere is a pale, featureless blue-green due to methane, which absorbs red light and reflects blue. Compared to Neptune, Uranus appears more muted. For years, scientists thought Uranus was a relatively quiet, boring world—until recent observations with advanced telescopes revealed complex storm systems and changing cloud patterns.

The Rings and Moons of Uranus

Though not as famous as Saturn’s rings, Uranus has 13 known rings, made of dark, narrow bands of dust and ice. These rings are relatively young in astronomical terms—perhaps just 600 million years old.

Uranus has 27 known moons, named after characters from the works of Shakespeare and Alexander Pope. Some of them are fascinating in their own right:

- Miranda: Known for its bizarre, patchwork surface of cliffs and valleys.

- Titania and Oberon: Large, icy moons that may have subsurface oceans.

- Ariel and Umbriel: Icy worlds with hints of geological activity.

Neptune—The Dynamic Blue Giant

Neptune is the eighth and farthest planet from the Sun. It is smaller than Uranus but more massive, leading to higher gravity and more dynamic weather.

A Deeper Blue

Neptune’s stunning deep blue color is also due to methane, but its richer hue suggests there are additional factors, possibly related to atmospheric particles or hazes that absorb and reflect light differently. Scientists are still working to solve the mystery of Neptune’s color.

Supersonic Winds and Giant Storms

Neptune boasts the fastest winds in the solar system, reaching speeds of 1,300 miles per hour (2,100 km/h). That’s faster than the speed of sound on Earth. Its atmosphere is a wild place, marked by giant storms, bright clouds, and whirlwind systems.

When Voyager 2 flew by in 1989, it spotted the Great Dark Spot, a massive storm roughly the size of Earth. By the time the Hubble Space Telescope looked again in 1994, the storm had vanished—only to be replaced by new ones elsewhere on the planet.

Neptune’s Rings and Moons

Neptune has five faint rings, named after astronomers who contributed to its discovery. They are clumpy, irregular, and short-lived, constantly replenished by the planet’s inner moons.

Neptune’s 14 known moons include one of the most fascinating satellites in the solar system: Triton.

Triton: A Captured World

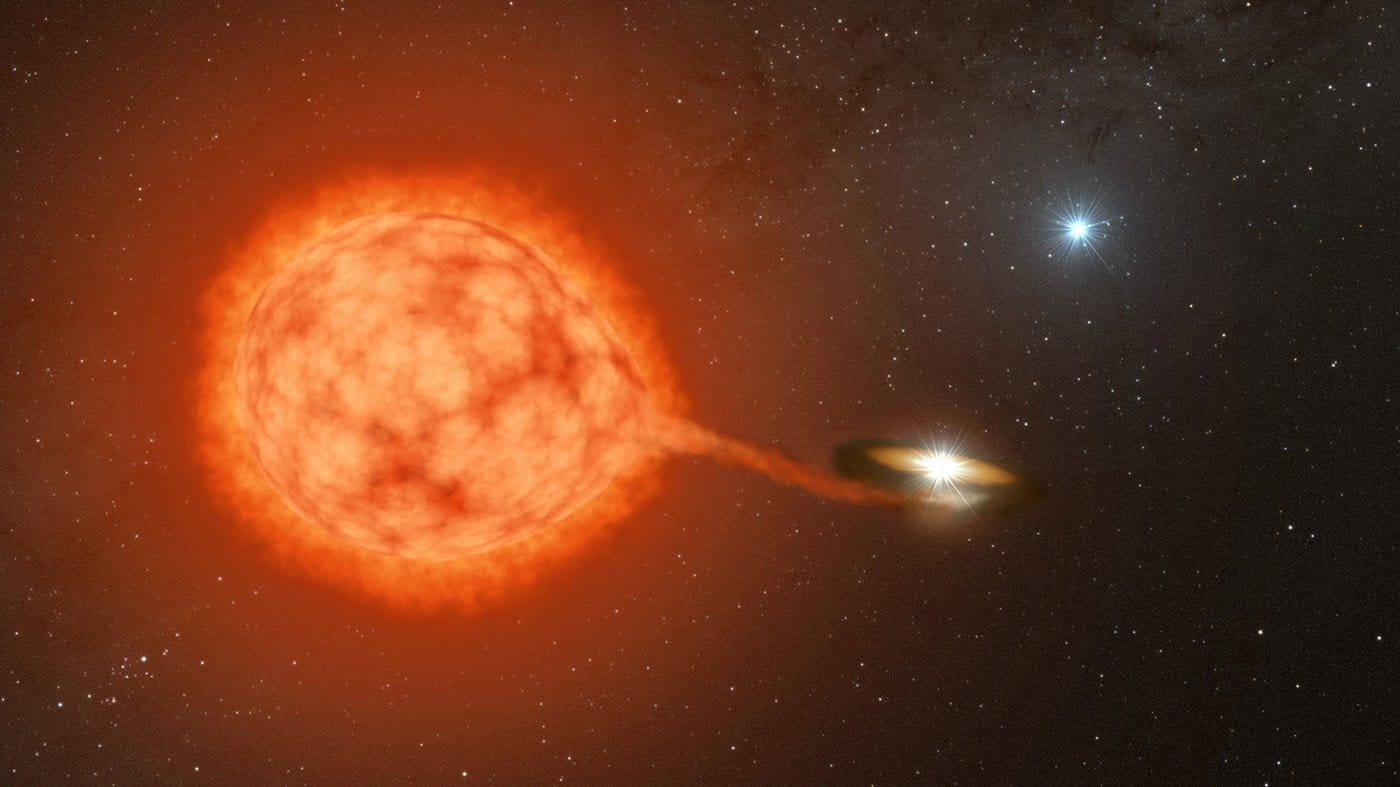

Triton is a retrograde moon, meaning it orbits Neptune backward, in the opposite direction of the planet’s rotation. This suggests Triton is a captured Kuiper Belt object, similar to Pluto.

Triton is icy and frigid, with geysers that erupt nitrogen gas into the thin atmosphere. Voyager 2 observed these geysers in 1989, making Triton the first place beyond Earth where active cryovolcanism was seen. Triton is thought to have a subsurface ocean, which raises the possibility (however remote) that it could harbor life.

Voyager 2—Our Only Visitor

Despite the importance of Uranus and Neptune, humanity has only visited them once, courtesy of NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft. Launched in 1977, Voyager 2’s “Grand Tour” of the outer planets took it past Jupiter and Saturn, and then on to Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

Voyager’s Discoveries

Voyager 2 gave us our only close-up images of Uranus and Neptune. It revealed Uranus’s ring system, discovered 10 new moons, and measured its strange magnetic field. At Neptune, it discovered the Great Dark Spot, measured the planet’s fierce winds, and observed Triton’s geysers.

But Voyager 2 was a flyby mission, not an orbiter. It captured snapshots, not detailed, long-term data. Since then, no spacecraft has returned to Uranus or Neptune, and our knowledge remains tantalizingly incomplete.

The Ice Giants and the Origins of the Solar System

Studying Uranus and Neptune is not just about curiosity—it’s essential to understanding how solar systems form and evolve.

Planetary Migration

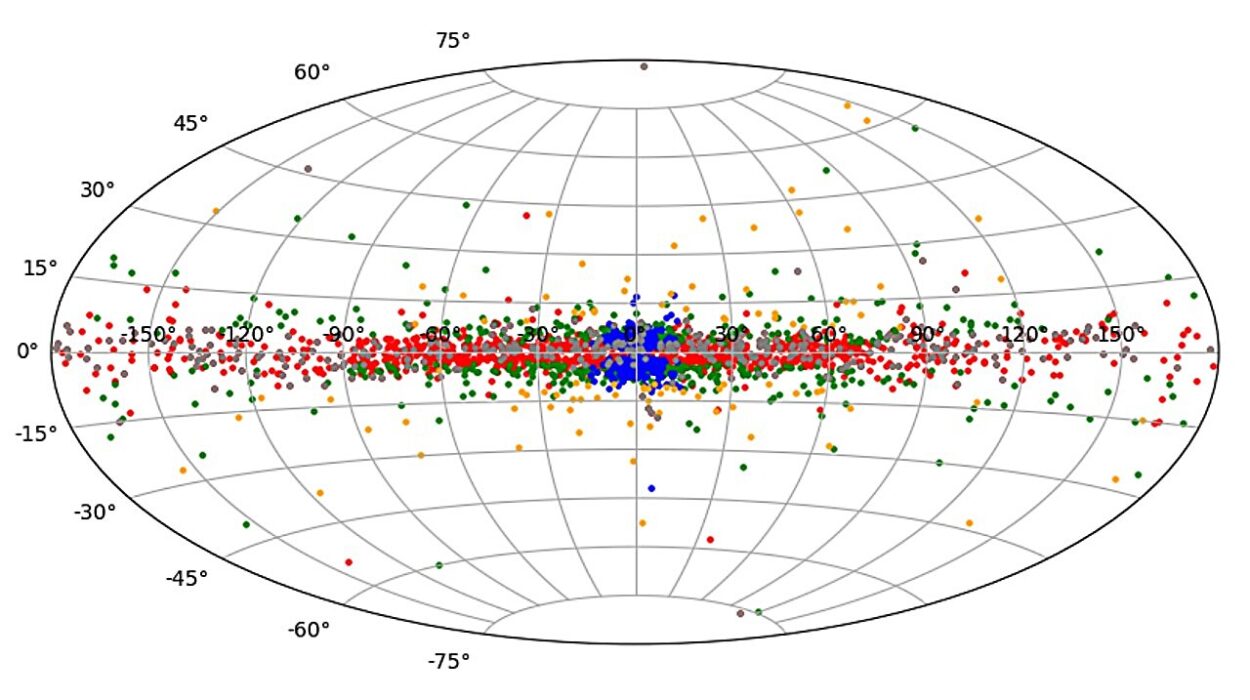

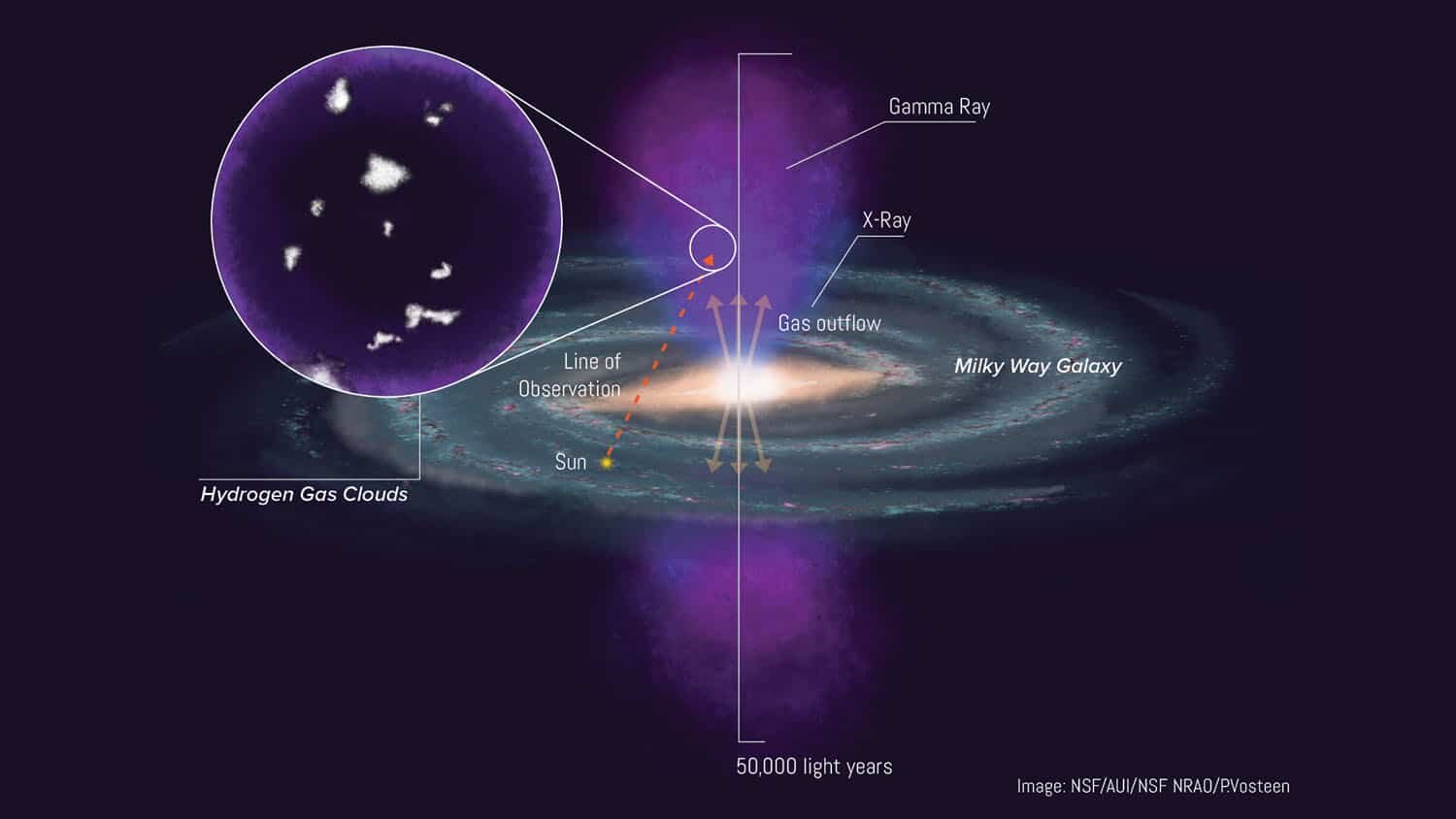

Many astronomers believe Uranus and Neptune didn’t form where they are today. Early in the solar system’s history, gravitational interactions between the gas giants and the debris of the young solar system caused planetary migration. Uranus and Neptune may have formed closer to the Sun and moved outward, scattering comets and debris as they went.

This migration may explain the existence of the Kuiper Belt, a distant region of icy objects beyond Neptune that includes Pluto.

Why Ice Giants Matter

Exoplanet surveys have revealed that Neptune-sized worlds are among the most common planets in our galaxy. By studying Uranus and Neptune, we can learn about these common planetary types and how they shape the formation and evolution of planetary systems.

Future Missions and The Promise of Exploration

For decades, scientists have dreamed of sending dedicated missions to Uranus and Neptune. Recently, NASA and other space agencies have seriously considered such missions.

Uranus Orbiter and Probe

In 2023, NASA prioritized a Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission as the next flagship mission after Mars Sample Return. Launching in the 2030s, this mission would orbit Uranus, drop a probe into its atmosphere, and conduct years of close-up studies of its rings, moons, and magnetic field.

Neptune and Triton Missions

Proposals have been made for missions to Neptune and Triton, including flybys, orbiters, and landers. Triton is of particular interest because of its potential subsurface ocean and geological activity.

Why Now?

The windows for these missions are closing, as Uranus and Neptune drift through their long seasons. Launch opportunities are limited, and without new spacecraft, our knowledge of the ice giants may remain stuck in the Voyager era for decades to come.

Conclusion: Secrets Await in the Cold and Dark

Uranus and Neptune, the ice giants of our solar system, are more than distant spheres of gas and ice. They are keys to understanding the origins of planets, the dynamics of atmospheres, and the potential for life in the cold outer reaches of the cosmos.

These two worlds are waiting for us to return—to peel back the clouds, to send probes into their atmospheres, and to unlock the secrets hidden beneath their icy exteriors. The next great discoveries in planetary science may not come from Mars or Jupiter, but from these distant, mysterious giants spinning in the dark.

The adventure is only beginning.