We rise with it. We bask in its warmth. Our ancestors worshipped it, and modern science studies it with ever-deepening fascination. The Sun—our life-giving star—is as old as time itself in human terms. And yet, it’s just one among billions of stars scattered across the vast, black ocean of the cosmos. Despite its everyday constancy, the Sun is living a life as complex and dramatic as any character in an epic saga. It was born from cosmic chaos, it lives in a delicate balance of forces, and one day—many billions of years from now—it will die, taking the inner planets of our solar system on its final, fiery journey.

This is the story of our Sun: a tale of creation, life, and inevitable destruction. It’s a story that reaches beyond Earth, offering a window into the life cycles of stars everywhere. And ultimately, it’s a story that makes us confront our own fragile existence within the grand scale of cosmic time.

The Birth of a Star

Long before Earth formed its rocky crust or the first spark of life flickered in ancient oceans, our Sun was nothing more than a swirling cloud of gas and dust adrift in the vastness of space. This cloud, known as a molecular cloud or stellar nursery, was cold and dark, made mostly of hydrogen—the simplest and most abundant element in the universe.

But even in deep space, gravity never sleeps.

Over time, some regions of this immense cloud grew denser under the slow, persistent tug of gravity. Eventually, one such dense pocket began to collapse in on itself. As it did, it started to spin, flattening into a disk with a bulging center. This spinning center was called a protostar, and around it, the material that wasn’t swallowed up began coalescing into the planets, moons, comets, and asteroids that would make up our solar system.

As the protostar collapsed, pressure and temperature at its core skyrocketed. When the temperature reached a staggering 10 million degrees Kelvin, something extraordinary happened: nuclear fusion ignited. Hydrogen atoms began fusing into helium, releasing an incredible amount of energy. The Sun had been born.

Roughly 4.6 billion years ago, our Sun took its place on the main sequence, the stable, longest phase in a star’s life. Balanced between the outward pressure from nuclear fusion and the inward pull of gravity, it began the slow, steady burn that would bathe Earth in warmth and light.

The Middle Age of the Sun – A Comfortable Stability

For billions of years, the Sun has burned with remarkable consistency. This middle-aged stability is no accident—it’s the result of perfect equilibrium between two titanic forces.

At its core, the Sun fuses 600 million tons of hydrogen into helium every second. This process releases photons, particles of light that bounce around inside the Sun for thousands of years before finally escaping into space. The energy created by this fusion provides the outward pressure that keeps the Sun from collapsing under its own immense gravity.

The Sun’s energy radiates outward, sustaining life on Earth and shaping the climate and weather. It powers photosynthesis, the process by which plants grow and release oxygen. It drives the water cycle. In every meaningful sense, our existence depends on this steady flow of energy.

But it’s not an entirely peaceful process. Occasionally, magnetic fields twist and snap on the Sun’s surface, giving rise to sunspots, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections. These bursts of solar activity can disrupt satellites and power grids on Earth, but they are minor ripples compared to what’s to come.

As main-sequence stars like our Sun burn hydrogen into helium, they gradually change. Over time, the Sun’s core becomes richer in helium, causing fusion to slow down slightly. In response, gravity begins to compress the core, raising its temperature and causing the outer layers to expand. This means that even now, the Sun is slowly growing brighter and hotter. Scientists estimate it’s about 30% brighter today than when life first emerged on Earth.

For now, we are living in a golden age of the Sun—a time when its light nourishes life, and its warmth sustains us. But nothing in the universe lasts forever.

The Sun’s Midlife Crisis – Changes on the Horizon

Stars like our Sun are incredibly resilient, but they are not immortal. They are machines with finite fuel, and eventually, the hydrogen in the Sun’s core will run out.

In about 5 billion years, the Sun will begin to experience a serious identity crisis. No longer able to fuse hydrogen at its core, gravity will gain the upper hand. The core will contract under its own weight, growing hotter and denser. Meanwhile, a shell of hydrogen surrounding the core will ignite, fusing furiously and releasing more energy than ever before.

This increased energy output will push the Sun’s outer layers outward. As it expands, the Sun will become a red giant—an enormous, swollen star many times its current size. Earth’s oceans will boil away. The atmosphere will be stripped. The surface will become a scorched wasteland. In fact, it’s likely that Earth will be engulfed entirely by the Sun’s outer layers, vaporized as the Sun swells outward toward Mars.

Mercury and Venus will be the first to go. Earth’s fate is still debated. Some scientists believe it will be swallowed, others that it may drift outward enough to avoid total destruction—but life, in any case, will have long since disappeared.

For around a billion years, the Sun will exist in this bloated red giant state. Its outer layers will be tenuous and cool compared to its current brilliant surface, and it will glow with a deep red hue. Deep in its core, something even more dramatic will be happening.

Helium Flash – The Last Great Fusion

As the core contracts and heats up, it will eventually reach temperatures high enough to ignite helium fusion. In a process called the helium flash, the Sun will begin fusing helium into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen. This phase is much shorter and more intense than the hydrogen-burning stage. The Sun will shrink slightly as this new fusion stabilizes the core temporarily.

But helium fusion is less efficient and produces less energy. It’s a stopgap measure, delaying the inevitable. The Sun simply doesn’t have enough mass to fuse heavier elements beyond carbon and oxygen. Only stars at least eight times the Sun’s mass can go on to create heavier elements like iron—leading to their spectacular deaths as supernovae.

Our Sun is destined for a quieter, though no less profound, ending.

The Death of the Sun – Becoming a White Dwarf

Once helium fusion ceases, the Sun will no longer be able to support itself. Its outer layers will be gently blown away into space, creating a dazzling planetary nebula—a glowing shell of gas and dust expanding outward from the dying star. These nebulae are among the most beautiful objects in the night sky, resembling colorful cosmic flowers blooming in the darkness.

At the center of this nebula, the Sun’s core will remain behind, no longer generating fusion but still incredibly hot and dense. This remnant is known as a white dwarf.

A white dwarf is a stellar corpse, about the size of Earth but containing nearly half the mass of the original Sun. It’s so dense that a teaspoon of its material would weigh tons. With no more fuel to burn, the white dwarf will gradually cool and fade over billions of years.

Eventually, long after the planetary nebula has dispersed, the white dwarf will cool to the point where it becomes a black dwarf—a cold, dark, and invisible remnant in space. However, the universe isn’t old enough yet for any black dwarfs to exist. It will take trillions of years for the Sun’s white dwarf remnant to cool to that state.

Legacy of the Sun – What Comes After

Though the Sun’s death seems distant and abstract, its legacy will be profound. The gas and dust blown off during its red giant and planetary nebula phases will enrich the surrounding space with heavier elements—carbon, oxygen, nitrogen—materials essential for life as we know it.

These elements will become part of new molecular clouds, forming the seeds for future stars and planets. Somewhere, perhaps billions of years after the Sun’s death, a new star system may form from its ashes. New worlds could arise, orbiting a new sun, containing the raw ingredients of life—the ultimate recycling program of the cosmos.

We owe our existence to stars like the Sun. The carbon in our bodies, the oxygen we breathe, the calcium in our bones—all forged in the hearts of long-dead stars. The Sun’s death, when it comes, will simply be one more link in the chain of stellar evolution that makes life possible.

Could We Survive the Sun’s Death?

Humans are a curious and resourceful species. Knowing what lies ahead, we can’t help but wonder: could humanity survive the Sun’s death?

In theory, yes—if we can master the art of interstellar travel. As the Sun grows hotter, Earth will become increasingly inhospitable. In about a billion years, the gradual increase in solar luminosity will boil away the oceans and end life as we know it. Long before the red giant phase, humanity (or its descendants) will need to find a new home.

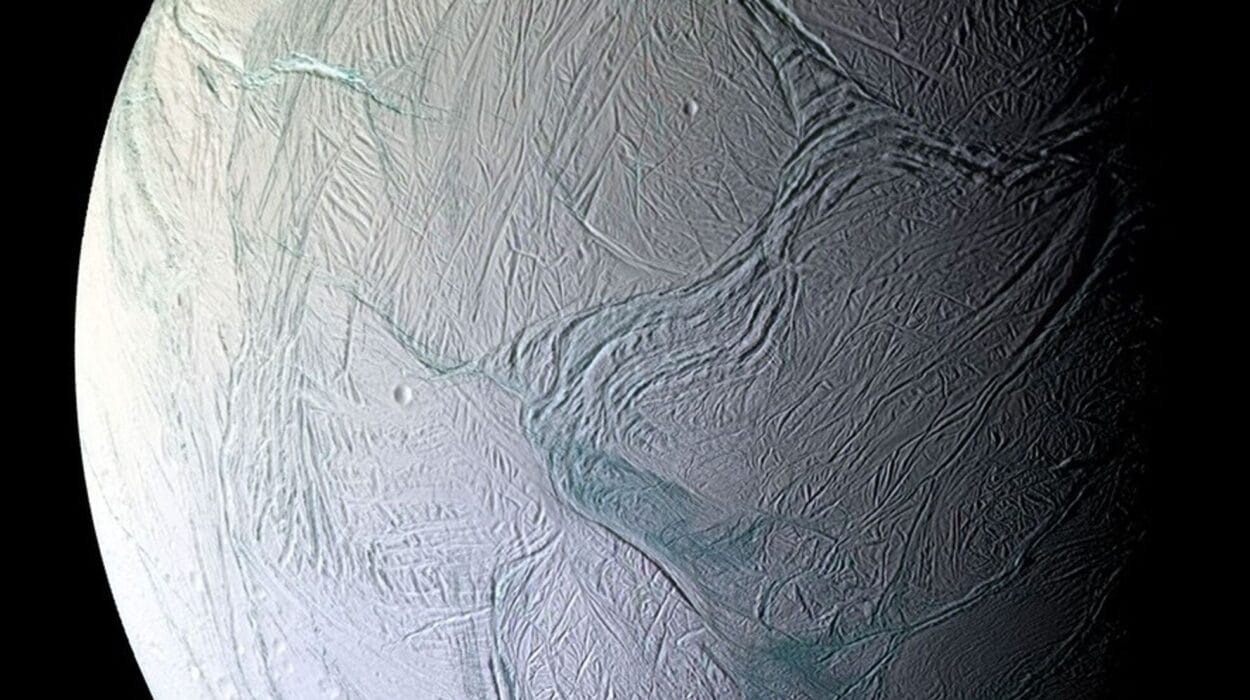

One possibility is to migrate outward, colonizing the outer planets or their moons. As the Sun expands, regions once frozen may become temperate. For example, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s Titan could potentially become habitable, warmed by the dying Sun.

Another possibility is leaving the solar system entirely. There are trillions of stars in the Milky Way, some of them younger and more stable than the Sun. If we develop the technology for long-duration space travel, we might find refuge around another star.

Or perhaps, we will build massive space habitats—artificial worlds that can sustain life indefinitely, independent of any star. These speculative megastructures, like O’Neill cylinders or Dyson spheres, remain firmly in the realm of science fiction for now—but who knows what the future holds?

Epilogue: The Cosmic Perspective

The Sun’s life story is one chapter in the grand narrative of the universe. It’s a tale of transformation, balance, and inevitability. It reminds us that nothing lasts forever, not even stars. Yet, in their lives and deaths, stars like the Sun give birth to new possibilities.

We are, in the most literal sense, made of stardust—born from the remnants of ancient stars that died billions of years ago. One day, the atoms that make up our Sun, our planet, and even ourselves may once again become part of something new, continuing the cosmic cycle.

When we look up at the Sun in the sky, we’re not just seeing a blazing ball of gas. We’re witnessing a star in its prime—one stage in a magnificent journey that began in the depths of a molecular cloud and will end in the quiet fading of a white dwarf.

In the vastness of time, the Sun’s life is a fleeting moment. But it’s a moment that gave rise to life, to consciousness, and to the incredible story of us.