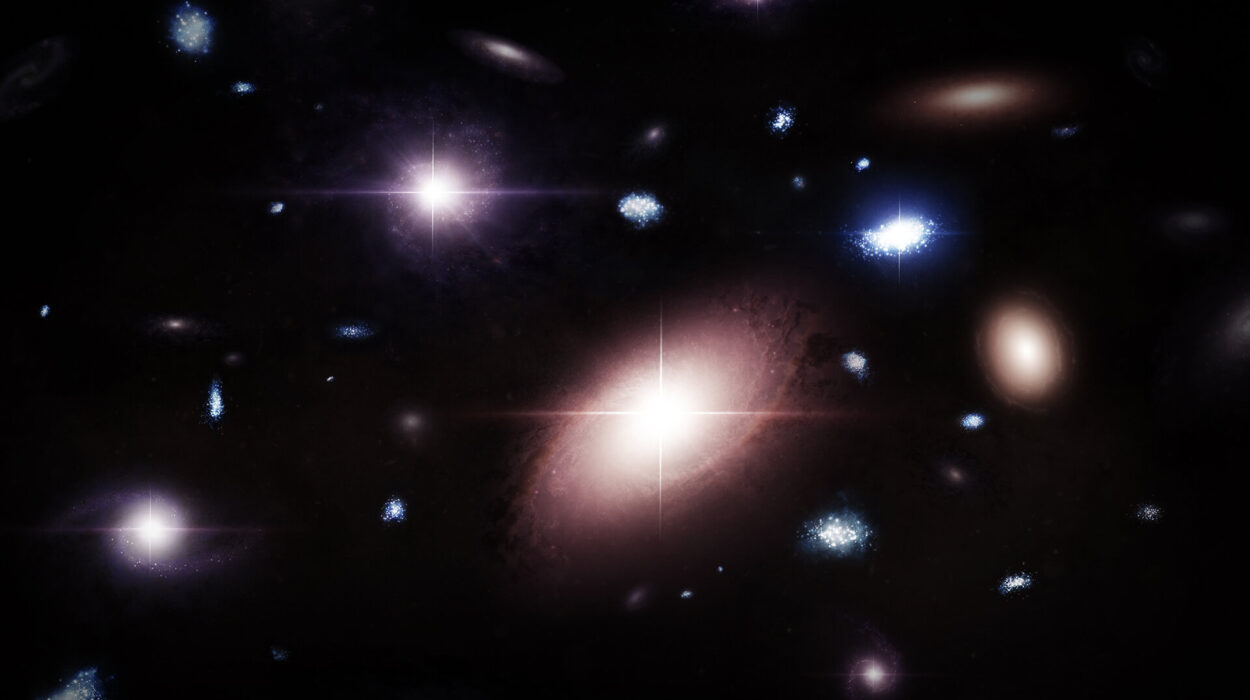

Look up at the night sky on a clear evening. There, hanging in the heavens, is Earth’s closest companion—the Moon. For as long as humans have gazed at the stars, the Moon has been an object of wonder, mystery, and fascination. Ancient peoples told stories of its creation, from gods crafting it from nothing to mythical animals swallowing and spitting it out. Poets have romanticized it, lovers have basked in its glow, and scientists have puzzled over its existence.

But beyond the myths and metaphors lies a question that has intrigued astronomers and planetary scientists for centuries: Where did the Moon come from? How did this pale satellite come to orbit Earth so serenely, locked in a cosmic dance that has lasted for billions of years?

In modern times, science has advanced enough to offer real answers. Yet even now, we are still unraveling the Moon’s origin story. The most widely accepted theory is the Giant Impact Hypothesis, which suggests that the Moon was born from a catastrophic collision between the young Earth and a Mars-sized object. But as we look deeper—examining isotopes, computer simulations, and lunar rocks—other possibilities emerge. Could the Moon have formed in a different way? Could the prevailing hypothesis be wrong, or at least incomplete?

Let’s embark on a journey through cosmic time and space, exploring the theories, evidence, and mysteries surrounding the Moon’s birth. We’ll delve into the science, the debates, and the possibilities—because the truth is, the story of the Moon is far from settled.

The Ancient Theories—First Attempts to Explain the Moon

Long before rockets and telescopes, humans speculated about the Moon’s origin. Ancient civilizations wove myths and legends to explain its presence.

In Greek mythology, Artemis, goddess of the Moon, drove her silver chariot across the night sky. In Chinese folklore, the Moon is home to Chang’e, a goddess who drank an elixir of immortality. The Aztecs told stories of the Moon being born from a self-sacrifice during the creation of the world.

But even among early philosophers, there were attempts at scientific reasoning. In the 5th century BCE, Anaxagoras suggested the Moon was a rocky body reflecting the Sun’s light, not a deity. Aristotle proposed that the Moon had always been there, orbiting Earth in a perfect, eternal cycle. And in the Middle Ages, thinkers like Johannes Kepler mused that the Moon was captured by Earth’s gravity.

By the time Galileo turned his telescope toward the Moon in 1609 and revealed its craters and mountains, the idea of a divine, perfect celestial body was fading. The Moon was a world in its own right—and its origins needed an explanation grounded in reality.

The Big Three—Early Modern Theories of Lunar Origin

By the 19th and early 20th centuries, scientists developed three primary hypotheses to explain the Moon’s origin. Each had its own merits—and its own fatal flaws.

1. The Fission Theory

Proposed by George Darwin (son of Charles Darwin) in the late 1800s, this theory suggested that the young, rapidly spinning Earth flung off a piece of itself due to centrifugal force. That ejected material coalesced into the Moon.

Proponents pointed to the Pacific Ocean basin as the possible “scar” left behind. It seemed to make sense—after all, the Earth and Moon share similarities in composition, particularly in their mantles.

But as scientists refined their understanding of angular momentum, they realized Earth would have needed to spin ridiculously fast—faster than was physically plausible—to fling off a chunk large enough to become the Moon. And the Pacific Ocean, it turns out, isn’t old enough or deep enough to be the mark of such a violent event.

2. The Capture Theory

What if the Moon formed elsewhere in the solar system and was later captured by Earth’s gravity? This theory posited that the Moon was a wanderer—a rogue body that Earth snagged as it passed by.

Capture scenarios can happen; many moons in the outer solar system, like Neptune’s Triton, are believed to be captured objects. However, capturing something as large as our Moon is tricky. It would require an extraordinary set of circumstances to slow down the Moon enough for Earth’s gravity to hold onto it. And if the Moon came from somewhere else, why is its composition so similar to Earth’s?

3. The Co-Accretion Theory

Perhaps Earth and the Moon formed together, side by side, from the same swirling disk of dust and gas around the Sun. This theory explained why their compositions are similar—they grew from the same material.

But there was a problem: the Moon doesn’t have much iron. Earth’s core is rich in iron, but the Moon has a relatively small iron core. If they formed together, why the difference? Co-accretion couldn’t fully explain it.

Each of these theories illuminated parts of the puzzle but left nagging questions unanswered. Then came a new idea—a bold, dramatic proposal that would change everything.

The Giant Impact Hypothesis—A Violent Birth

In the 1970s, a new theory emerged that took the scientific world by storm: the Giant Impact Hypothesis, also known as the “Big Splat.”

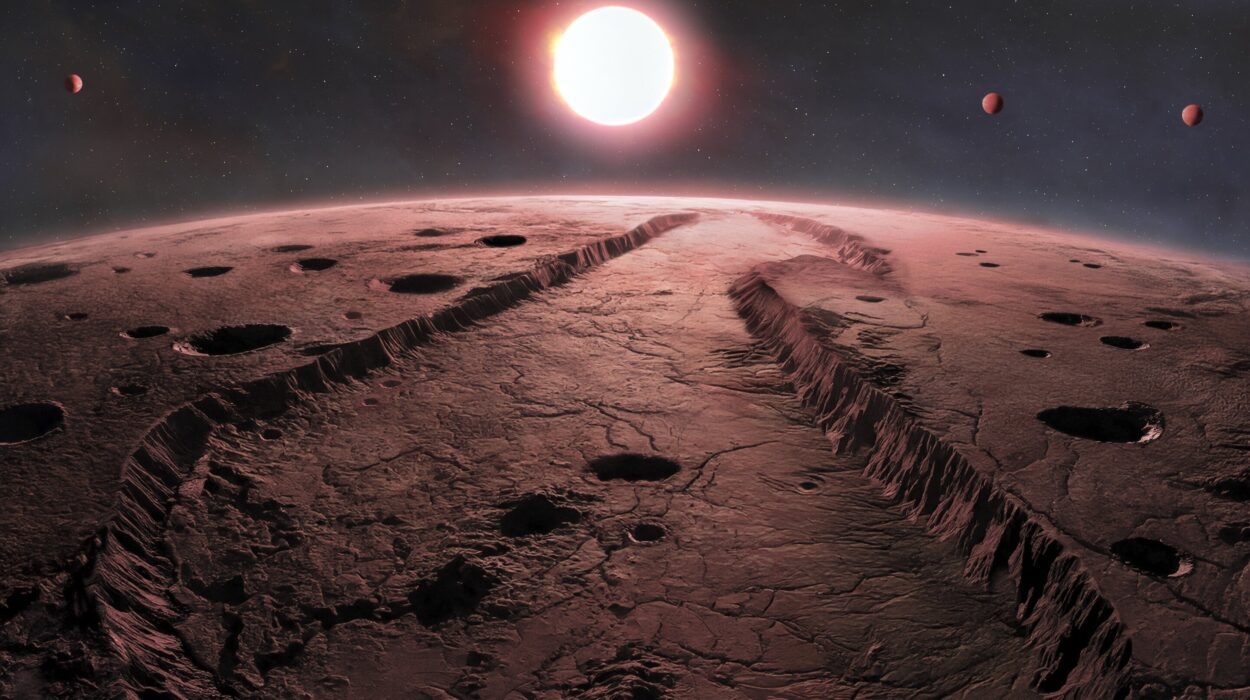

According to this model, about 4.5 billion years ago, when Earth was still a young, molten planet, it collided with a Mars-sized body. Scientists have named this theoretical impactor Theia, after the Greek titaness who gave birth to Selene, goddess of the Moon.

Theia slammed into Earth in a glancing blow. The impact was catastrophic—spewing vast amounts of debris into orbit. Over time, this debris coalesced, forming a molten disk around Earth. That molten material eventually clumped together under gravity’s pull and cooled to become the Moon.

This theory elegantly explained several mysteries:

- The Moon’s composition: The Moon is made largely of material from Earth’s mantle, which accounts for its similar isotopic makeup.

- The lack of iron: Theia’s iron core may have merged with Earth’s, leaving the Moon deficient in heavy metals.

- The Moon’s orbit and rotation: A giant impact could account for the Moon’s angular momentum and its synchronous rotation (it always shows the same face to Earth).

It was a neat, dramatic solution. And it seemed to fit the available evidence. But as with any scientific theory, it faced tests—and new evidence would complicate the story.

The Evidence—What Moon Rocks Reveal

In 1969, the Apollo 11 mission returned the first samples of lunar rock to Earth. Over the next few years, six Apollo missions brought back more than 800 pounds (about 380 kilograms) of Moon rocks.

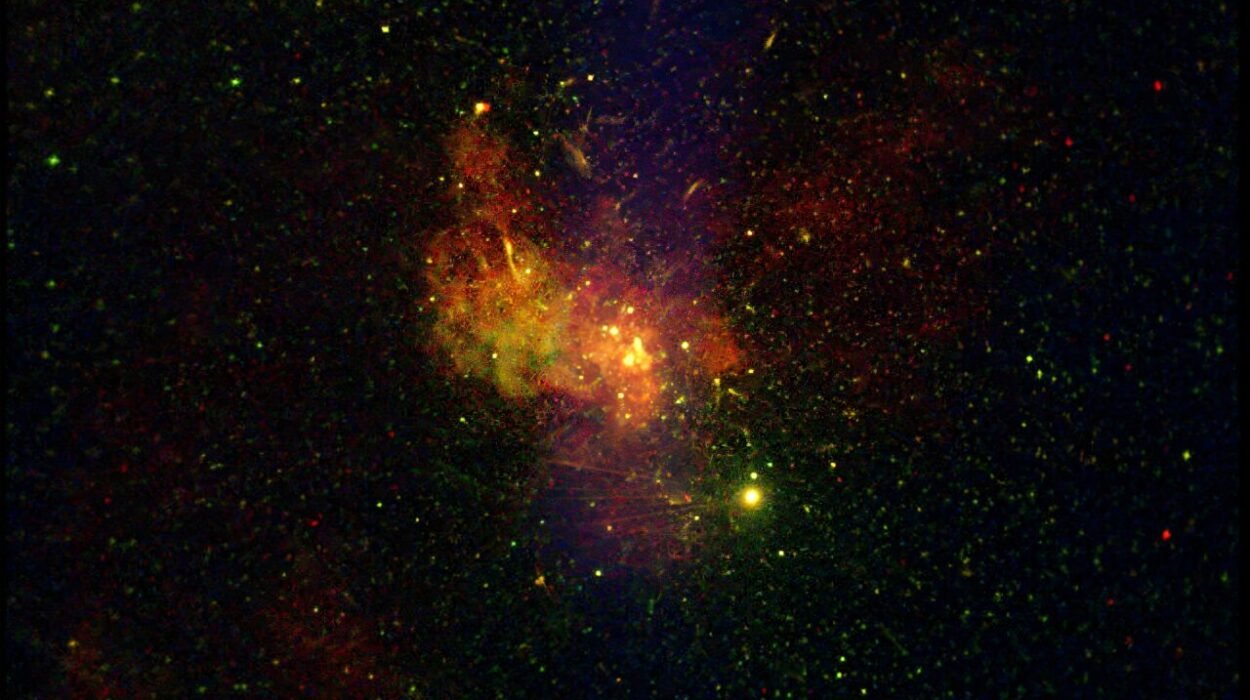

These ancient stones told a story of intense heat and violent formation. Some rocks had crystallized from molten material, supporting the idea that the Moon was once a global magma ocean. Other samples revealed a surprising fact: the oxygen isotopes in Moon rocks are almost identical to those on Earth. If the Moon formed from debris mixed with Theia’s material, shouldn’t it show different isotopic fingerprints?

This was one of the first cracks in the simple Giant Impact model. If Theia came from elsewhere in the solar system, it should have had a different isotopic signature.

Further analysis revealed more surprises:

- The Moon is drier than Earth, suggesting that volatile elements were vaporized in an extreme heat event.

- Yet certain volatile elements, like sodium and potassium, exist on the Moon in greater quantities than the Giant Impact model would predict.

These conflicting clues raised new questions. Did the impact completely homogenize Earth and Theia? Did Theia come from the same region as Earth, accounting for their similarity? Or was something missing from the theory?

New Twists—Refining the Giant Impact Model

To address these puzzles, scientists proposed modified versions of the Giant Impact Hypothesis.

1. Hit-and-Run Collisions

Some models suggest Theia only grazed Earth, and much of Theia escaped, leaving mostly Earth-derived debris to form the Moon. This could explain the isotopic similarity.

2. Vaporized Earth Model

Other simulations propose that the collision vaporized much of Earth’s outer layers, mixing thoroughly with Theia’s debris before forming the Moon. This could account for the nearly identical isotopes.

3. Synestia Hypothesis

In 2017, a new concept called a synestia was proposed. A synestia is a doughnut-shaped mass of vaporized rock formed by massive impacts. In this scenario, Earth temporarily became a hot, spinning cloud of rock vapor, with the Moon forming inside this vast structure. As Earth cooled and condensed, the Moon would have already formed from the outer material, explaining their similarities.

These ideas pushed the boundaries of planetary science. Yet none provided a perfect fit. The more we learned, the more complex the story became.

Alternative Theories—Could It Be Something Else?

As scientists refined the Giant Impact Hypothesis, others explored different possibilities.

1. Multiple Smaller Impacts

Instead of one colossal smash, could Earth have experienced dozens or hundreds of smaller impacts? Each collision could have launched debris into orbit, eventually forming the Moon. This “accretion by many impacts” theory could explain isotopic similarities, as the material would mostly come from Earth.

2. Co-Formation with Unique Conditions

Revisiting co-accretion, some scientists wonder if unique conditions in the early solar system allowed Earth and the Moon to form together, but with different compositions due to how material accreted.

3. The Exotic Theories

There are even more unconventional ideas:

- Could Earth have once had two moons that collided to form the single Moon we see today?

- Was the Moon formed by processes we don’t yet understand, such as quantum anomalies or ancient cosmic events lost to time?

While some of these ideas are speculative, they highlight how much we still have to learn.

The Moon’s Influence on Life and Earth

Whatever its origin, the Moon has profoundly shaped life on Earth.

1. Stabilizing Earth’s Axis

The Moon’s gravity stabilizes Earth’s axial tilt, which affects our climate. Without the Moon, Earth might wobble chaotically, leading to extreme climate swings that could have made life difficult.

2. Tides and Ocean Life

The Moon’s gravitational pull creates tides, which have shaped the evolution of life. Tidal pools may have been crucial environments where early life transitioned from water to land.

3. Timekeepers and Culture

For early humans, the Moon was a natural calendar. Its cycles guided planting, harvesting, and religious ceremonies. Its presence has been woven into the fabric of human culture, art, and spirituality for millennia.

Future Exploration and New Clues

Human exploration of the Moon is far from over.

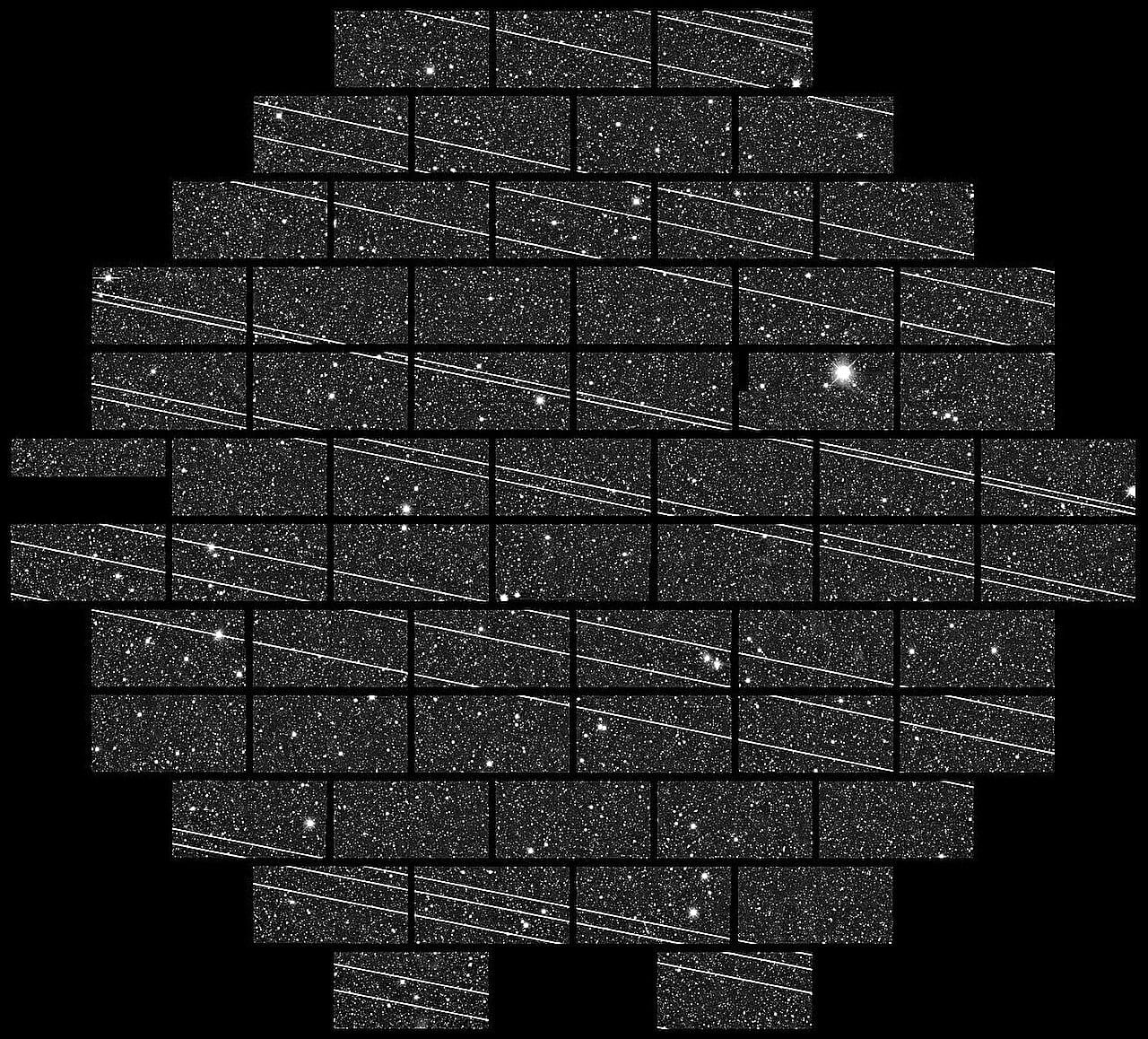

NASA’s Artemis program, private companies like SpaceX, and international efforts are planning new missions to explore the Moon’s surface and deep interior. Upcoming missions aim to bring back new samples, search for water ice in permanently shadowed craters, and perhaps establish a long-term human presence.

With new technology, we may answer some of the lingering questions about the Moon’s formation. And as we look outward—toward Mars, the asteroid belt, and beyond—the Moon may become a stepping stone to the stars.

Conclusion: The Moon’s Story—Still Being Written

The Moon’s origin story is one of cosmic violence, mystery, and beauty. Whether born of a giant impact, a series of collisions, or another process yet to be discovered, our Moon stands as a silent witness to the chaotic birth of the solar system.

As we learn more, we deepen not just our understanding of the Moon, but of ourselves—our planet’s history, our place in the cosmos, and the delicate dance of forces that made life on Earth possible.

The Moon may be familiar, but its story is still unfolding. And as we continue to explore, the next chapter may reveal secrets beyond our wildest imagination.