Imagine two cups of water. One is steaming hot; the other is lukewarm. You place both in a freezer at the same time. Now, which one do you think will freeze first? Logic says the cooler one, right? But sometimes, nature has a surprising answer: the hot water freezes first.

Welcome to the world of the Mpemba effect, a phenomenon so strange and counterintuitive that it has baffled scientists for centuries. And while this peculiar quirk of physics is not new, modern science is finally starting to unravel its mysteries in ways that could have big implications for technology, energy, and even quantum computing.

What Exactly Is the Mpemba Effect?

At its simplest, the Mpemba effect refers to situations where hotter substances cool more quickly than their cooler counterparts, sometimes even freezing faster. Most famously, this has been observed with water—boiling water sometimes freezes faster than cold water under the same conditions. But the effect isn’t limited to water; it’s shown up in other materials and physical systems, too.

This defies everyday intuition and basic thermodynamics. After all, doesn’t hotter stuff need to cool down more before it freezes? Shouldn’t the colder sample have a head start? That’s what most of us would think. And yet, experiments going back to ancient times have shown that things aren’t always so simple.

A Brief History of a Longstanding Mystery

Aristotle mentioned something like the Mpemba effect as early as the 4th century BCE. Centuries later, Renaissance thinkers like Francis Bacon and René Descartes wrote about similar observations. But the effect faded into obscurity until 1963, when it was thrust back into the scientific spotlight by a Tanzanian secondary school student named Erasto Mpemba.

Mpemba noticed that when he made ice cream, hot milk seemed to freeze faster than cold milk. His teachers dismissed him, but Mpemba persisted. Later, working with physicist Denis Osborne, he showed the effect was real, and they published a paper together in 1969. Since then, the phenomenon has borne Mpemba’s name.

Why Has the Mpemba Effect Been So Hard to Explain?

Despite its notoriety, the Mpemba effect has resisted a clear-cut explanation. Over the years, scientists have proposed all kinds of theories: evaporation of hot water reducing mass, convection currents stirring things up, differences in supercooling, dissolved gases, and changes in the properties of hydrogen bonds in water molecules.

But there’s a bigger problem: inconsistent results. Some experiments show a clear Mpemba effect, while others don’t. The outcome often depends on the exact setup—temperature ranges, container types, purity of substances, and even the surrounding environment. Because of these variables, scientists have struggled to come up with a universal theory that explains when and why the Mpemba effect happens.

The Kyoto Breakthrough: A New Way to Measure Cooling Mysteries

Enter Tan Van Vu and Hisao Hayakawa, two theoretical physicists from Kyoto University who are taking a fresh approach. In their recent paper published in Physical Review Letters, they tackled one of the biggest challenges in Mpemba effect research: how do you measure it?

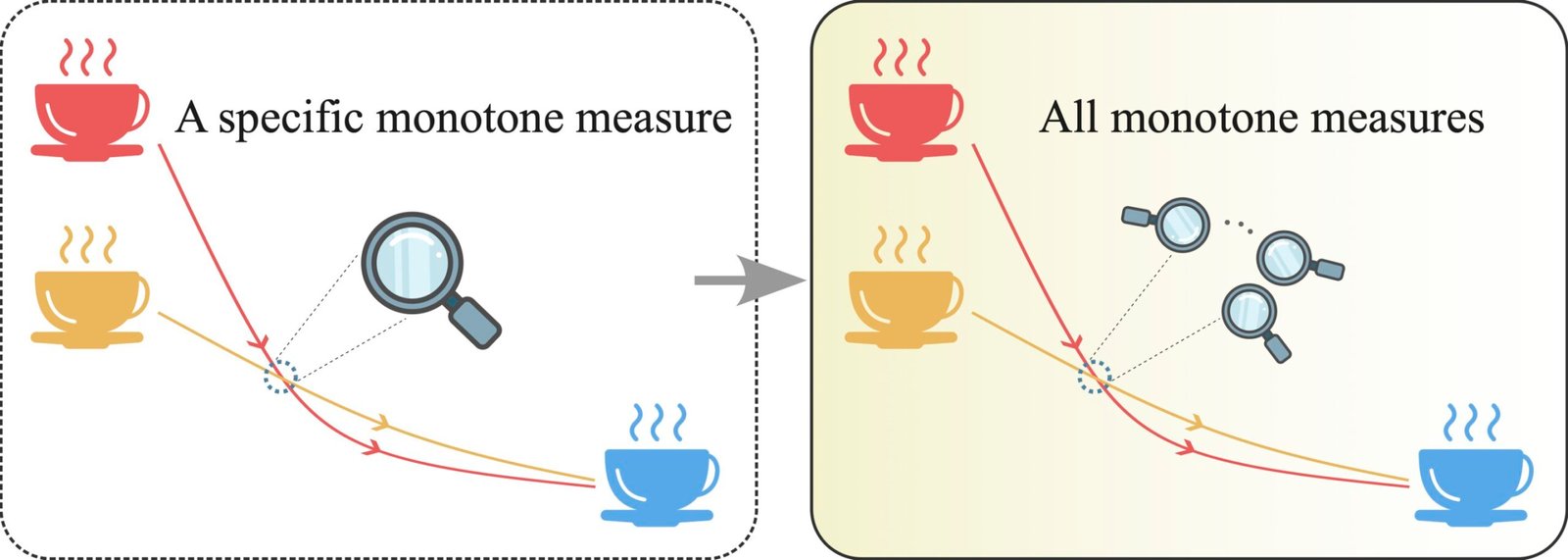

Until now, detecting the Mpemba effect depended on which mathematical tool or distance measure you used to compare how fast two systems cooled. Imagine timing two runners in a race but using different stopwatches—one in seconds, another in minutes. Depending on the stopwatch, you might get different answers. That’s essentially what was happening in Mpemba research. Depending on the mathematical “stopwatch,” sometimes the effect appeared; sometimes it didn’t.

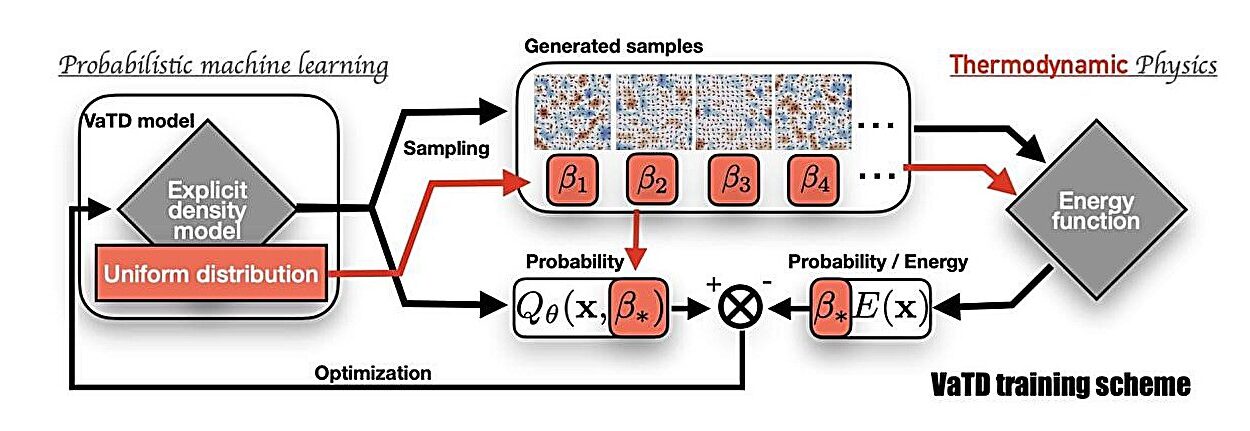

Vu and Hayakawa realized this inconsistency was a major roadblock. So, they turned to a sophisticated framework called thermomajorization theory, which is widely used in statistical physics and quantum thermodynamics. It allows scientists to compare the disorder, or entropy, of different thermodynamic states in a consistent way.

Their key innovation was to define something they call the thermomajorization Mpemba effect. Instead of relying on one specific distance measure, this approach considers all possible monotone distance measures simultaneously. (In plain English: they took into account every reasonable way you could measure cooling without violating the laws of thermodynamics.)

By doing this, they created a rigorous and universal test for the Mpemba effect that works no matter what mathematical ruler you use. For the first time, scientists have a consistent criterion for determining when and where the Mpemba effect occurs.

What Makes This Discovery So Important?

Vu and Hayakawa’s framework finally removes a huge source of ambiguity. Instead of arguments over which measure to use, scientists can focus on what really matters: understanding the physics behind the effect and exploring its implications.

And their findings go further. Using their thermomajorization approach, they showed that the Mpemba effect is not restricted to particular temperature ranges. It can emerge at any temperature, depending on the system and its dynamics.

That insight opens up a world of possibilities.

Beyond Ice Cubes: Why the Mpemba Effect Matters

At first glance, a quirky freezing trick might seem like a mere curiosity. But the Mpemba effect is fundamentally about how systems relax to equilibrium, or how they lose energy and settle down. This process is crucial in physics, chemistry, engineering, and even biology.

Vu believes their findings could impact a wide range of technologies:

- Heat engines and refrigeration systems: By understanding and potentially harnessing faster relaxation times, engineers might design more efficient machines.

- Quantum computing: One of the biggest challenges in quantum tech is rapidly cooling qubits (quantum bits) to their ground states so they can be used in computations. Faster thermal relaxation could speed up initialization, making quantum computers more practical and powerful.

- Materials science: Better understanding of relaxation dynamics could help develop new materials that respond faster to temperature changes, improving sensors or energy storage devices.

The Future: What’s Next for Mpemba Research?

So far, Vu and Hayakawa’s work has focused on classical stochastic processes, meaning systems where probabilities evolve over time in a predictable (Markovian) way. But they’re already looking ahead.

Into the Quantum World

Their next goal? Extending the thermomajorization Mpemba effect to open quantum systems, which are described by quantum master equations, like the famous Lindblad equation. This would allow them to explore quantum relaxation dynamics, a frontier area with huge implications for quantum thermodynamics and quantum information theory.

Non-Markovian Mysteries

They also want to explore non-Markovian systems, where the system’s future depends not just on its present state but also on its past history. Many real-world systems, from biological processes to complex materials, have memory effects, and understanding how the Mpemba effect plays out there could uncover new physical principles.

Speed Limits and Time Constraints

One tantalizing open question they’re asking: What’s the minimum timescale at which the Mpemba effect can occur? By investigating the speed limits of relaxation, they might establish fundamental constraints on how fast systems can settle down, a concept with echoes in both classical and quantum physics.

Conclusion: A Quirky Phenomenon With Big Potential

The Mpemba effect started as a curious observation by a high school student making ice cream. But today, it’s at the cutting edge of thermodynamics, statistical physics, and quantum theory. Thanks to Vu and Hayakawa’s groundbreaking work, we now have a rigorous and unified way to understand this phenomenon, free from past ambiguities.

And as researchers continue to probe deeper into the mechanics of how hot things sometimes cool faster than cold things, we may uncover new principles of energy, entropy, and time that change the way we think about the physical world—and how we engineer it.

So, the next time you make ice cubes, remember: there’s a mystery of the universe at play in your freezer, and we’re only just beginning to understand it.

Reference: Tan Van Vu et al, Thermomajorization Mpemba Effect, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.107101. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2410.06686