Have you ever stared up at the night sky and wondered just how vast the universe really is? As we sit on our little planet, orbiting an unremarkable star in an average galaxy, we often think of the universe as everything that exists. But what if it isn’t? What if the universe we know is just one bubble in an infinite cosmic ocean? Welcome to the mind-bending concept of the Multiverse—a theory that suggests there might be not one universe but many… possibly an infinite number of them.

If that sounds like science fiction, you’re not alone. The idea of the multiverse has fascinated philosophers, scientists, and storytellers for centuries. But in recent decades, serious physicists and cosmologists have been exploring multiverse theories as more than fantasy. Could it be true? Are we living in just one of countless parallel realities? And if so, what does that mean for us?

Buckle up. We’re about to take a deep dive into one of the most fascinating and controversial ideas in science.

What Exactly Is the Multiverse?

At its most basic, the multiverse is the idea that our universe—everything we can observe and measure—is just one of many universes. These other universes might have different laws of physics, different histories, and even different versions of you.

There isn’t just one version of the multiverse theory, though. Scientists and philosophers have come up with several models, each offering different possibilities for what these other universes could be like.

But before we explore them, let’s rewind a bit.

For most of human history, we believed Earth was the center of everything. Then we realized we orbit the Sun. Later, we discovered our solar system was just one of billions in the Milky Way. And our galaxy? Just one of possibly two trillion in the observable universe.

Every time we thought we understood our place in the cosmos, we found out we were wrong. The multiverse idea might be the next great step in that humbling tradition.

The Scientific Foundations of the Multiverse

So where did this idea come from? The multiverse isn’t just some wild fantasy cooked up by daydreamers. It has roots in serious science, especially in cosmology, quantum physics, and string theory.

Here are some of the key scientific ideas that lead to the multiverse concept.

1. Cosmic Inflation and the Bubble Universes

The theory of cosmic inflation was proposed in the 1980s by physicist Alan Guth. It describes a period of incredibly rapid expansion just after the Big Bang. During this time, the universe grew exponentially, far faster than the speed of light (don’t worry—this doesn’t break Einstein’s rules because space itself was expanding).

Here’s the twist: some versions of the inflation theory suggest that inflation doesn’t stop everywhere at once. Instead, while inflation stops in one region (giving birth to a universe like ours), it continues in other regions. Those regions can form bubble universes, each disconnected from the others and potentially with different physical laws.

Think of it like popcorn popping. Each pop creates a new universe, and there’s no reason to think it stops at just one kernel.

This leads to the idea of eternal inflation, where new universes are continually forming, forever.

2. Quantum Mechanics and Many-Worlds

In the strange world of quantum mechanics, particles exist in multiple states at once until they’re observed or measured. This is called superposition. Once measured, the particle “chooses” a state, but what if it doesn’t really choose?

The Many-Worlds Interpretation, proposed by physicist Hugh Everett in 1957, suggests that when a quantum event happens, the universe splits into different branches. In one branch, the particle goes left; in another, it goes right. And this isn’t limited to particles—if you flip a coin, there’s a universe where it lands heads and another where it lands tails.

In other words, every possible outcome actually happens, but in different universes. There could be an unimaginably vast (possibly infinite) number of worlds branching out from every decision, every possibility.

In one universe, you became a rock star. In another, you never existed.

3. String Theory and the Landscape Multiverse

String theory tries to explain all the fundamental particles and forces in terms of tiny, vibrating strings. But for string theory to work, it requires more dimensions than the four we experience (three of space and one of time). Some versions suggest up to 11 dimensions!

With so many dimensions, there are tons of ways to arrange them, and each arrangement could result in a universe with different physical laws.

This leads to the idea of a landscape multiverse, where each possible arrangement of these extra dimensions creates a different universe. Some of these universes might be utterly alien—imagine a universe where gravity is so strong that stars can’t form, or one where atoms don’t even exist.

4. The Anthropic Principle

Why does our universe seem so perfectly tuned for life? The strength of gravity, the mass of electrons, the force of electromagnetism—all these constants have just the right values to allow stars, planets, and eventually life.

This is known as the fine-tuning problem.

Some scientists suggest that if there’s a multiverse, with countless universes having different physical laws and constants, we shouldn’t be surprised to find ourselves in a universe where life is possible. In universes where the conditions aren’t right, there’s no one there to ask the question.

This is the anthropic principle—we observe a life-friendly universe because we’re here to observe it.

Types of Multiverse Theories

The multiverse isn’t a single idea—it’s a collection of different theories and models. Let’s take a tour through the major types of multiverses scientists and thinkers have proposed.

1. Level I: Beyond Our Cosmic Horizon

The simplest version of the multiverse is a Level I multiverse. This doesn’t require any exotic physics—just more space.

Our universe has a cosmic horizon because light has only had 13.8 billion years to travel. There’s a limit to how much of the universe we can see. But beyond that horizon, space likely continues.

If space is infinite (as many cosmologists believe), there are infinite regions beyond our view. In fact, if there’s infinite space, and if matter is distributed randomly, eventually the patterns of matter would repeat. There might be another Earth out there, with someone reading this article—perhaps in a slightly different language.

Level I multiverses are like parallel universes very far away, rather than in separate dimensions.

2. Level II: Bubble Universes (Eternal Inflation)

Level II multiverses come from the eternal inflation theory we mentioned earlier. Each bubble universe might have different physical laws, particles, and dimensions.

In this model, the laws of physics aren’t universal. What’s true in one bubble may be false in another. Some universes might be lifeless, others might be unrecognizable to us, and a few might be teeming with life.

3. Level III: Many-Worlds Quantum Multiverse

This level comes from the Many-Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics. Every time a quantum event happens, the universe branches into different versions of itself.

In Level III, there are parallel universes constantly branching off from every possible event. There’s no need for infinite space or cosmic inflation—these universes coexist in an ever-branching tree of possibilities.

You’re making decisions all the time, and each one may lead to a different version of yourself in a different universe.

4. Level IV: The Ultimate Multiverse

This one’s wild.

Proposed by cosmologist Max Tegmark, the Level IV multiverse suggests that all mathematical structures exist. If something can be described mathematically, it exists somewhere.

This includes universes that are completely different from ours—maybe with different logic, different mathematics, or even completely unimaginable physics.

It’s the ultimate “anything goes” multiverse, where all conceivable realities are realized.

Could We Ever Prove the Multiverse Exists?

This is the big question. Science relies on evidence, and the multiverse, by its very nature, might be beyond our observational reach.

Still, some scientists believe there might be ways to find indirect evidence.

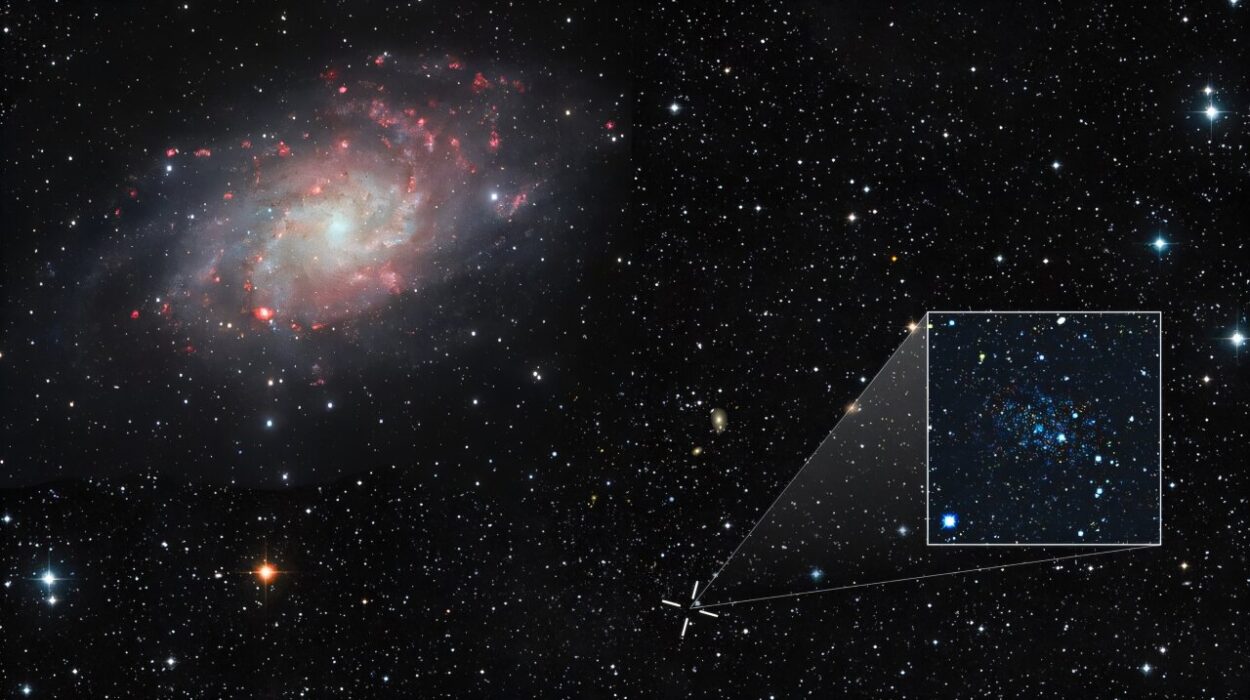

1. Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB)

The CMB is the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, a snapshot of the early universe. Some physicists have looked for patterns or “bruises” in the CMB that could suggest our universe bumped into another one.

So far, the evidence is inconclusive, but future observations might offer more clues.

2. Dark Energy and Fine-Tuning

Some scientists argue that the discovery of dark energy—a mysterious force accelerating the universe’s expansion—could point to the multiverse.

If there are many universes with different values of dark energy, we might just happen to live in one with the right value for galaxies (and life) to form.

3. Quantum Computing and Many-Worlds

Some proponents of the Many-Worlds Interpretation argue that quantum computers could provide evidence for parallel universes.

Quantum computers perform calculations using qubits, which can exist in multiple states at once. Some physicists speculate that quantum computers might be using computational resources from other universes… though this is highly speculative.

What Would the Multiverse Mean for Us?

If we’re part of a multiverse, it raises profound questions about our place in the cosmos, free will, and identity.

1. Are There Copies of You?

If the multiverse exists, there could be countless versions of you. In some universes, you might have made different choices—studied a different major, moved to a different city, or married someone else.

In others, you might not exist at all. Or maybe you’re a completely different being, living in a universe with different physics.

2. Does Free Will Exist?

The Many-Worlds Interpretation suggests that every possible outcome happens somewhere. If every decision spawns new universes, do we really have free will? Or are all possibilities inevitable in some universe?

It’s a deep philosophical question. Some argue that free will still matters, because you experience making a choice. Others think it’s an illusion.

3. Are We Special?

If there are infinite universes, are we special at all? Some find this humbling or unsettling.

But others find it liberating. We exist in a universe where life is possible. We have consciousness, curiosity, and the ability to ask these questions. In an infinite multiverse, our universe is precious because it’s ours.

The Multiverse in Popular Culture

The multiverse isn’t just a scientific theory—it’s a playground for storytellers.

From comic books to movies, the idea of parallel universes has captured our imaginations.

- Marvel’s Multiverse Saga explores alternate versions of beloved heroes and villains.

- DC Comics has its own multiverse, where different Earths feature different versions of Superman and Batman.

- Movies like Everything Everywhere All At Once delve into multiverse hopping, exploring themes of identity and choice.

- TV shows like Rick and Morty revel in the absurd possibilities of parallel realities.

- Philip K. Dick, H.G. Wells, and Jorge Luis Borges all explored multiverse-like ideas in literature.

Why are we so obsessed with the multiverse? Maybe it’s because we all wonder what if—what if we made different choices, what if the world was different, what if reality itself was stranger than we imagined?

Skepticism and Criticism

Not everyone is on board with the multiverse. Some critics argue that the multiverse is untestable and therefore unscientific.

If we can’t observe other universes, how can we test the theory? Is it science or philosophy?

Physicist Sabine Hossenfelder has argued that multiverse theories often rely on mathematical beauty rather than empirical evidence. Others, like Roger Penrose, are skeptical of theories like eternal inflation.

But many physicists argue that the multiverse is a natural consequence of our best theories. If inflation, quantum mechanics, and string theory lead to a multiverse, we should take the idea seriously.

Final Thoughts: Are We Living in One of Many?

We don’t know for sure if the multiverse exists. But the idea challenges our understanding of reality and our place in it.

Whether or not we ever find definitive proof, the multiverse forces us to confront deep questions about existence, possibility, and identity. Are we unique? Are there endless versions of ourselves? Is reality far stranger than we can imagine?

As science advances, we may one day find answers. Until then, the multiverse remains one of the most fascinating ideas in modern science—and a reminder that the cosmos is vast, mysterious, and full of wonder.

Maybe we are living in one of many universes. And maybe, just maybe, somewhere out there, another version of you is reading this same article… wondering the same thing.