In the hilly landscape of northern Greece, beneath the shadows of the ancient city of Aigai—once the resplendent capital of Macedonia—lies a burial site that has fascinated historians and archaeologists for nearly half a century. The Great Tumulus of Vergina, unearthed in 1977, was hailed as one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in Europe. Among the hidden chambers within this massive burial mound was a tomb so richly adorned and symbolically complex that some scholars believed it held the remains of Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. But a new and remarkable study suggests that this tomb—the so-called Tomb of Persephone—may not belong to Philip at all. Instead, it opens a far deeper mystery about identity, politics, and the eternal enigma of ancient death.

The Tumulus and the Dynasty

To understand the significance of this revelation, one must first step back in time. In the fourth century BCE, Macedonia was transforming from a regional backwater into a political powerhouse under the Argead Dynasty. Philip II, a brilliant strategist and charismatic leader, solidified Macedonia’s power, creating the conditions for his son, Alexander, to launch one of the most breathtaking military campaigns in human history.

Vergina (ancient Aigai) served as the burial ground for the Argead kings. It was a sacred city, a place where royal rituals played out, and where the dead were honored with splendor befitting their earthly dominance. The Great Tumulus, a monumental artificial mound, concealed several tombs believed to hold members of this ruling family. Among them was one particular tomb with stunning wall frescoes and unusual architecture—dubbed the Tomb of Persephone for the vivid painting of the goddess of the underworld adorning its walls.

For decades, many believed this tomb held the bones of Philip II, his last wife Cleopatra, and their newborn child—victims, perhaps, of a ruthless political purge orchestrated by Philip’s former wife Olympias, the mother of Alexander. This hypothesis was tantalizing, drawing scholars into passionate debates, books, and documentaries. But even in the glow of scholarly certainty, questions remained.

A New Generation, A New Inquiry

Now, a new international team of scientists—comprising archaeologists, biologists, chemists, and historians from institutions across Europe and the United Kingdom—has shaken the foundations of this long-held assumption. Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, their research combined cutting-edge techniques in bioarchaeology with the latest radiocarbon dating and isotopic profiling, peeling back the layers of time with unprecedented precision.

Their goal was simple yet profound: to re-examine the human remains buried within the Tomb of Persephone, using the most advanced scientific methods available. What they found was startling.

Unveiling the Dead: Bones That Speak

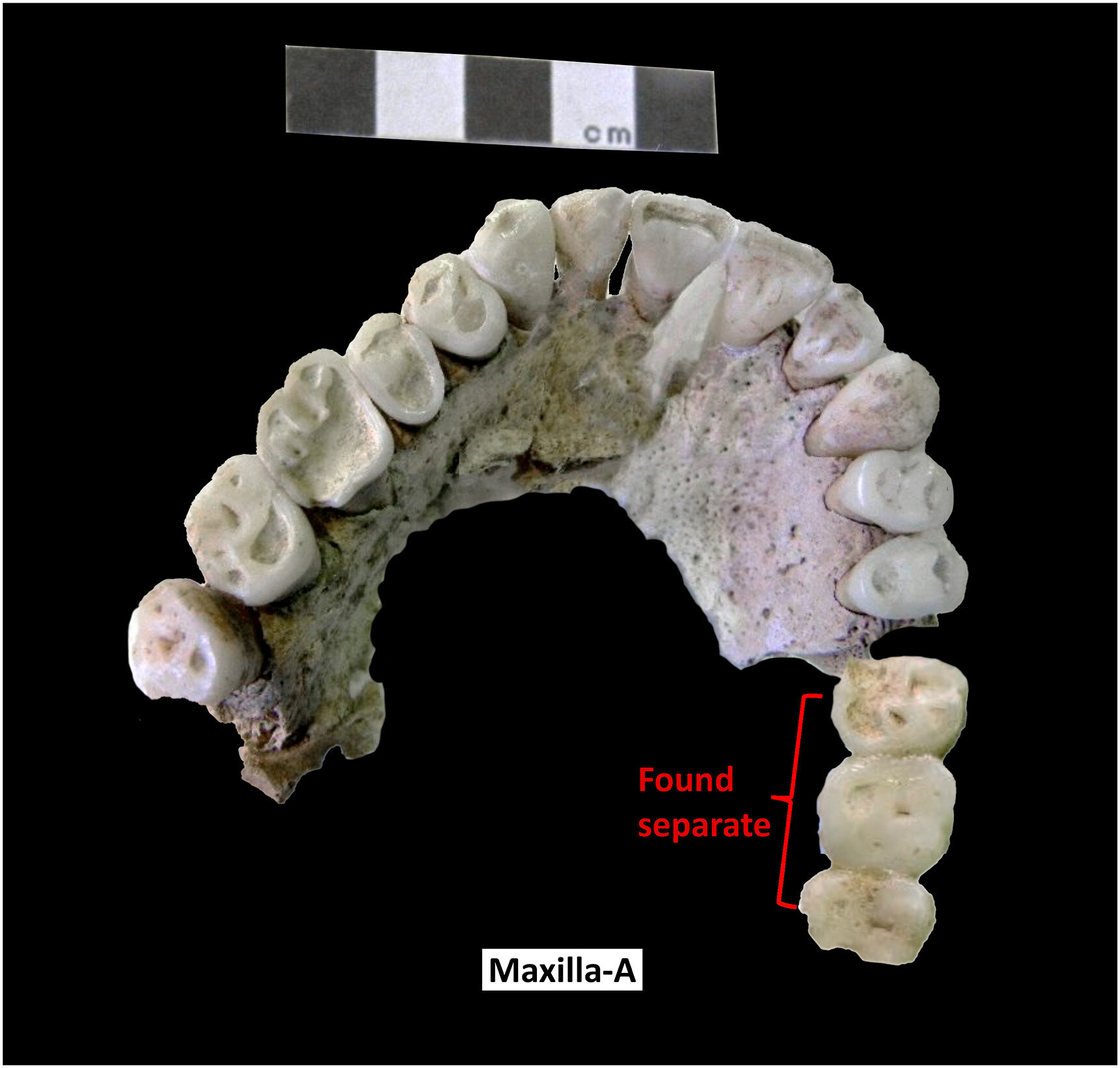

The remains previously attributed to Philip II and Cleopatra were meticulously analyzed. The male skeleton, central to the tomb’s story, was determined to have belonged to a man between the ages of 25 and 35 at the time of death. Philip, according to every historical source, was in his mid-forties when he was assassinated in 336 BCE—older, weathered, and already marked by wounds sustained in battle. The skeleton also showed no evidence of the famously documented limp or eye injury that Philip sustained during a siege.

Equally compelling was the analysis of the female remains. Long assumed to be Cleopatra—Philip’s last wife—the skeleton lacked any definitive markers to support such an identity. Moreover, there was no evidence that she had died in childbirth, as earlier theories had suggested. In fact, the most haunting revelation came from the other bones found in the tomb: fragments from up to six different infants, all interred centuries later than the two adults.

This ruled out any possibility that the babies were the couple’s children. Rather than a tragic royal family slain in a conspiracy, the burial appeared more complex—perhaps even symbolic. These later infant burials suggest the tomb held a continuing cultural or spiritual significance long after its original use.

The Fall of a Theory and the Rise of Mystery

The findings are seismic. They effectively eliminate the Tomb of Persephone as the final resting place of Philip II, upending nearly five decades of assumption. But as one theory falls, a thousand new questions rise.

If not Philip and Cleopatra, then who were these two adults? Why were they buried with such apparent honor and artistic grandeur? What is the significance of the Persephone fresco, with its themes of abduction, death, and return? And why were infants added to the tomb long after the original interment?

The researchers offer no definitive answers, only careful speculation. The male and female skeletons, they suggest, may have belonged to high-status individuals—perhaps elite members of the Macedonian court or religious officials. The elaborate decoration of the tomb may reflect their importance, though not necessarily royal lineage.

The later infant burials could reflect ritual practices or an effort to associate the newly dead with an already sanctified space. In ancient Greece, particularly in Macedon, tombs were not just final resting places—they were sites of power, memory, and even political propaganda.

Science Illuminates History

This discovery exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary science in solving historical riddles. The researchers used radiocarbon dating to anchor the skeletons in time. Isotopic analysis of teeth and bones revealed details about the individuals’ diets and geographic origins, helping to rule out royal identities based on what is known about elite Macedonian life.

DNA analysis, though limited by the degraded state of the bones, confirmed that the infant remains came from multiple individuals, unrelated to each other or to the adults. These weren’t a family buried together—they were a patchwork of the dead, laid to rest in a space already hallowed by mystery.

Importantly, the team also used CT scanning and forensic reconstruction to better understand skeletal anomalies and injury patterns. None matched what is known of Philip II, whose body was historically described as disfigured from years of warfare.

A Broader Historical Reframing

The implications of this study extend far beyond one tomb. If the Tomb of Persephone is not Philip’s, then where is he buried? Many now believe that Tomb II, another chamber beneath the Great Tumulus discovered at the same site, might be the true burial place of Philip II. This tomb contains an adult male with a healed leg injury and a damaged eye socket—injuries that align closely with historical accounts of the Macedonian king.

This reorientation reframes our entire understanding of the Great Tumulus. It forces a reassessment of how we connect archaeology with ancient texts and reminds us that even the grandest assumptions must be continually tested.

A Story That Still Unfolds

In many ways, the mystery of the Tomb of Persephone is emblematic of ancient history itself—an intricate puzzle of fragmentary evidence, dramatic storytelling, and the relentless pursuit of truth. We build narratives from bones and pottery, frescoes and inscriptions, always aware that new tools may yet tell different stories.

What remains undisputed is the tomb’s beauty and significance. The Persephone fresco—a vivid depiction of the goddess being carried to the underworld by Hades—speaks to the cultural and spiritual values of the time. Death was not the end, but a journey. And the tomb itself, whether royal or noble, played a part in shaping that journey.

Perhaps that is what the ancient builders intended—not just to preserve the dead, but to provoke eternal curiosity in the living.

Conclusion: A Monument to the Unknown

As archaeologists pack away their tools and scientists log their final data, the Tomb of Persephone continues to whisper secrets from the shadows of the past. The two adults entombed there—once mistaken for the most famous couple in ancient Macedon—remain anonymous, but their story has grown richer, not poorer, for it.

Science has corrected a misconception, but it has also unveiled a deeper mystery. Who were these people? What lives did they lead? What customs, tragedies, or beliefs led to their burial in such a poignant and symbol-laden space?

In the end, the Tomb of Persephone may never give up all its secrets. But in its silence and ambiguity, it challenges us to keep looking, keep questioning, and above all, to keep remembering that history is not static. It is a living conversation between the past and the present—one that we are all invited to join.

Reference: Yannis Maniatis et al, New scientific evidence for the history and occupants of tomb I (“Tomb of Persephone”) in the Great Tumulus at Vergina, Journal of Archaeological Science (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2025.106234

Loved this? Help us spread the word and support independent science! Share now.