Imagine a vast, icy realm, so distant from Earth that even light, traveling at 186,000 miles per second, would take nearly a year to get there. A dark, silent, cosmic frontier where ancient relics of the Solar System drift in slow, stately orbits. This is the Oort Cloud—a mysterious outer shell that envelopes our entire planetary system in an almost incomprehensible sphere of ice, rock, and cosmic time capsules.

While no human-made spacecraft has ever come close to it, and no telescope has yet directly observed it, the Oort Cloud remains one of the most captivating and enigmatic regions in astronomy. It is, in many ways, the Solar System’s final frontier—a place where the Sun’s gravitational influence weakens and interstellar space begins. But what exactly is the Oort Cloud, how did we discover it, and why does it continue to fascinate scientists and space enthusiasts alike?

This journey will take us through the history, structure, and significance of the Oort Cloud. We’ll delve into its mysterious origins, explore the comets that are its heralds, and ponder the cosmic questions it raises. By the end of this odyssey, you’ll have a deep appreciation for this cold, distant realm that guards the Solar System like a silent sentry.

What Is the Oort Cloud?

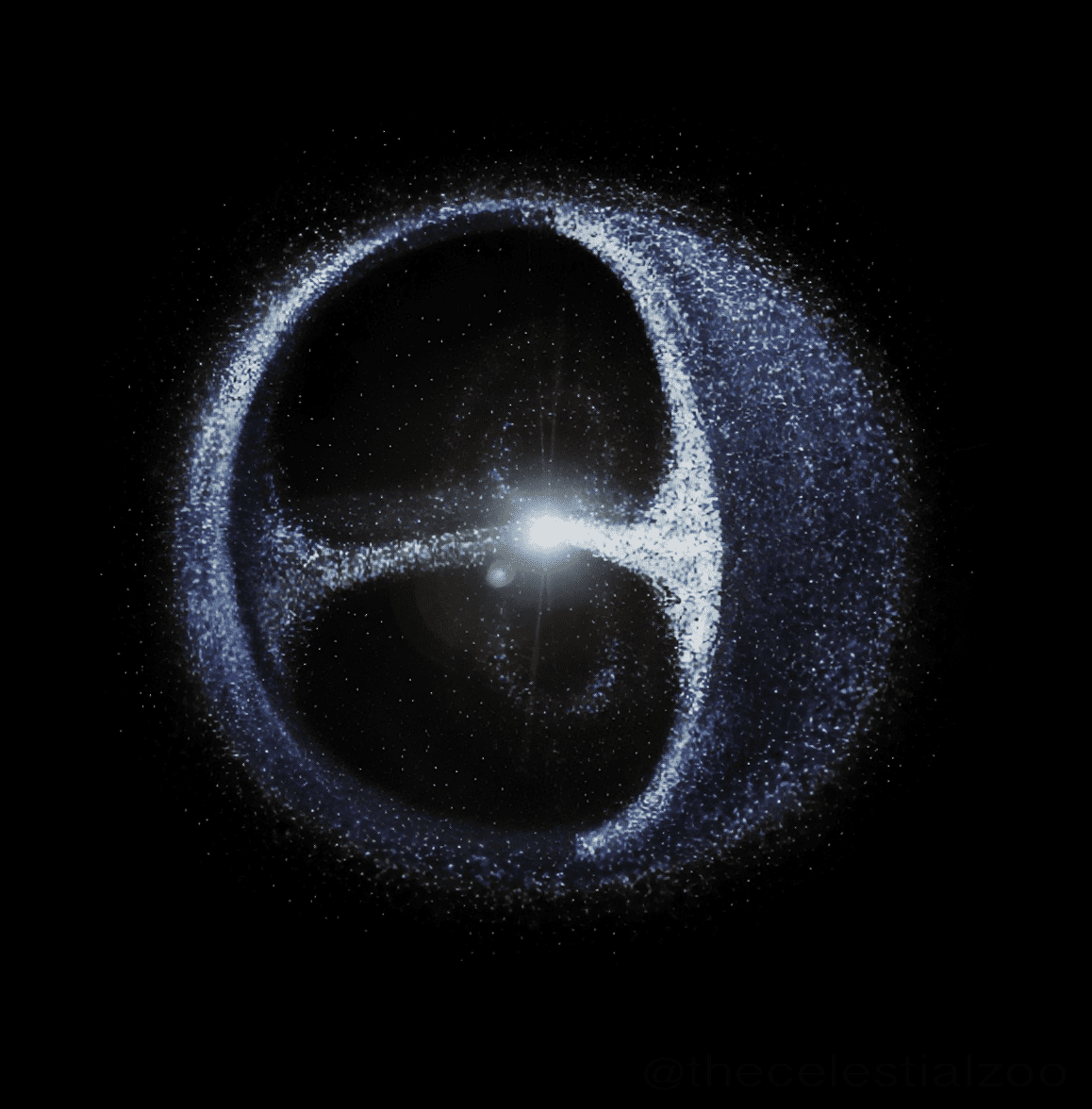

The Oort Cloud is a theoretical concept—a giant spherical shell of icy objects that exists at the outermost edges of the Solar System. While we have not observed it directly, astronomical evidence strongly suggests its presence. It is believed to be a reservoir of billions, perhaps trillions, of icy bodies. These objects are the source of long-period comets—those that take hundreds, thousands, or even millions of years to orbit the Sun.

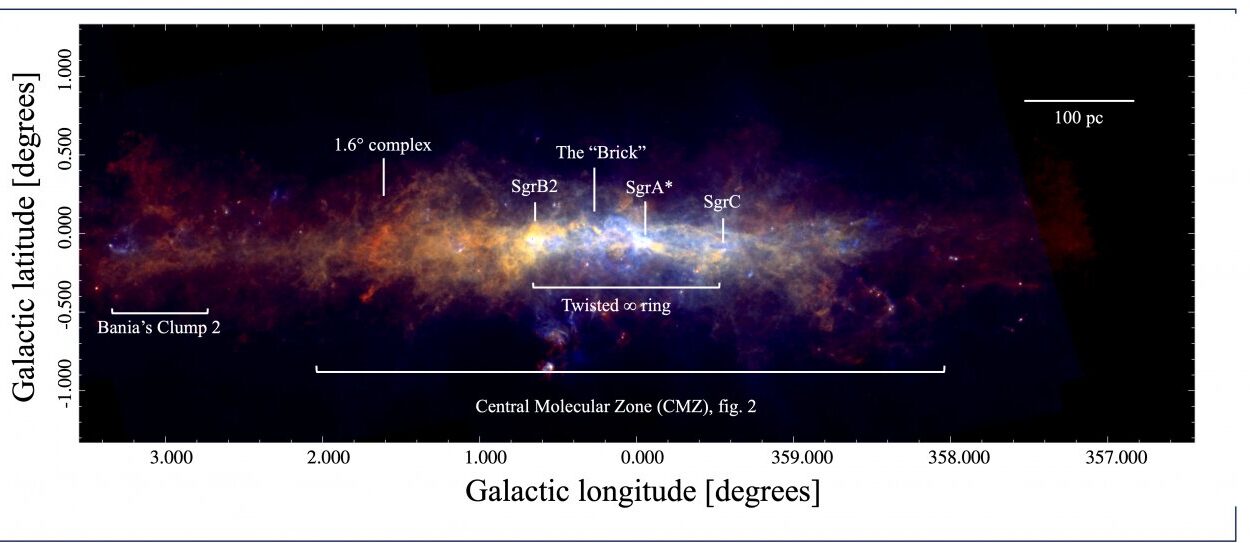

The Oort Cloud begins far beyond the orbit of Neptune, past the Kuiper Belt and scattered disc. While the Kuiper Belt (where Pluto resides) ends around 50 Astronomical Units (AU) from the Sun (1 AU is the distance from Earth to the Sun), the Oort Cloud is thought to extend from about 2,000 AU to as far as 100,000 AU—or nearly 1.5 light-years away. This puts the outer edge of the Oort Cloud nearly halfway to the nearest star system, Proxima Centauri.

The objects within the Oort Cloud are mostly icy planetesimals, leftovers from the Solar System’s formation. They are frozen relics, unchanged for billions of years, holding clues to the conditions that existed when the Sun and planets first coalesced from a swirling disk of gas and dust.

A Cloud Named After a Visionary

The Oort Cloud is named after the Dutch astronomer Jan Oort, who first hypothesized its existence in 1950. Oort was grappling with a puzzle that had perplexed astronomers for centuries—the origin of comets.

Comets, with their brilliant tails and glowing comas, had long been known to appear seemingly at random in Earth’s skies. Some comets returned on predictable orbits, like Halley’s Comet, while others seemed to arrive from deep space, never to be seen again. Where were they coming from? And why did so many have orbits suggesting they originated from the outer reaches of the Solar System?

Oort analyzed the orbits of long-period comets and noticed a pattern. These comets had aphelia (the points in their orbits farthest from the Sun) that clustered at extreme distances. This implied a source far beyond the known planets. He proposed that an enormous spherical cloud of icy bodies existed at the outer limits of the Sun’s gravitational influence, sending comets into the inner Solar System when their orbits were disturbed—by passing stars, galactic tides, or other forces.

Although Jan Oort’s idea built on earlier suggestions by Estonian astronomer Ernst Öpik, it was Oort who rigorously developed the theory and connected it to observational data. Thus, this hypothetical region became known as the Oort Cloud.

The Structure of the Oort Cloud

The Inner and Outer Oort Cloud

Scientists hypothesize that the Oort Cloud has two main regions:

- The Inner Oort Cloud, also known as the Hills Cloud, lies closer to the Sun, starting around 2,000 AU and extending out to about 20,000 AU. It is denser than the outer cloud and may act as a reservoir that replenishes the Outer Oort Cloud.

- The Outer Oort Cloud is an enormous spherical shell that stretches from about 20,000 AU to perhaps 100,000 AU or more. The outer cloud contains objects that are only weakly bound to the Sun by gravity. These distant bodies are most susceptible to being nudged by galactic tides or passing stars, occasionally sending them hurtling toward the inner Solar System as long-period comets.

The entire Oort Cloud is thought to be shaped by the gravitational influences of nearby stars and the tidal forces of the Milky Way galaxy. While the inner region might be more disk-shaped or toroidal, the outer region is largely spherical.

Population and Composition

How many objects exist in the Oort Cloud? Astronomers estimate that there could be trillions of icy bodies larger than a kilometer in diameter, and countless smaller fragments. These objects are likely made of water ice, ammonia, methane, and other frozen volatiles—similar to comets that we observe up close.

The total mass of the Oort Cloud is uncertain. Some estimates suggest it may contain a few Earth masses’ worth of material, while others propose more conservative figures. Despite its size and population, the objects in the Oort Cloud are spread thinly across a vast space, making direct observation incredibly challenging.

The Birth of the Oort Cloud

Formation in the Early Solar System

The story of the Oort Cloud’s formation begins more than 4.6 billion years ago when the Sun was just an infant star surrounded by a rotating disk of gas and dust. In this protoplanetary disk, particles collided and stuck together, forming larger bodies that eventually became the planets, moons, asteroids, and comets we know today.

In the outer regions of this disk, beyond the orbit of the giant planets, icy planetesimals formed in abundance. However, the gravitational influence of Jupiter and Saturn was so strong that many of these objects were flung out of the early Solar System altogether. Some escaped into interstellar space, but others were captured by the Sun’s gravity in distant, stable orbits, forming what would become the Oort Cloud.

The Role of the Galactic Neighborhood

During this chaotic period, the Solar System was not an isolated system. It was born in a crowded stellar nursery, where neighboring stars frequently passed close by. These stellar encounters helped sculpt the orbits of the Oort Cloud objects, pulling them into more distant and spherical distributions.

Over time, as the Sun and its family of planets settled into the relatively quiet outskirts of the Milky Way, the Oort Cloud remained as a distant halo of icy leftovers. Its formation and structure are a testament to the turbulent early history of the Solar System and the gravitational forces that continue to shape it today.

Long-Period Comets—Visitors from the Oort Cloud

What Are Long-Period Comets?

Long-period comets are icy wanderers that originate in the Oort Cloud. Their orbits are highly elongated, with periods ranging from thousands to millions of years. Unlike short-period comets, which come from the Kuiper Belt and return frequently, long-period comets make one grand appearance and often do not return for eons—if at all.

When one of these distant objects is nudged by a passing star or galactic tide, its orbit can be altered, sending it plunging toward the inner Solar System. As it approaches the Sun, the comet’s ice begins to vaporize, creating a glowing coma and long, bright tails that make it visible from Earth.

Famous Long-Period Comets

Some of the most spectacular comets in history have been long-period comets:

- Comet Hale-Bopp (C/1995 O1): Discovered in 1995, this bright comet was visible to the naked eye for a record 18 months and became one of the most observed comets of the 20th century.

- Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON): Hailed as a potential “Comet of the Century,” ISON broke apart during its close encounter with the Sun in 2013 but provided valuable data for astronomers.

- Comet Hyakutake (C/1996 B2): This comet passed close to Earth in 1996 and displayed a spectacular tail stretching across the sky.

These icy emissaries remind us of the vast, hidden population of objects in the Oort Cloud—waiting to make their dramatic journey into the inner Solar System.

The Oort Cloud and Cosmic Threats

Comet Impacts on Earth

Comets from the Oort Cloud have likely played a role in Earth’s history, both as bringers of water and organic molecules and as potential agents of mass extinction. The idea that comets delivered the building blocks of life to early Earth is a popular hypothesis. These frozen bodies contain organic compounds, amino acids, and water ice—ingredients necessary for life as we know it.

On the darker side, large comet impacts can be catastrophic. Scientists believe that a massive impact, possibly from a comet or asteroid, contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Although the probability of a comet impact in the near future is low, the vast population of the Oort Cloud makes it a long-term source of potential threats.

Cosmic Disturbances

The orbits of Oort Cloud objects are so delicate that minor disturbances can have major consequences. Passing stars, molecular clouds, or even the gravitational tides of the Milky Way can send comets toward the inner Solar System. Some scientists have even speculated about the existence of an undetected companion star, dubbed “Nemesis,” that could periodically disturb the Oort Cloud and trigger comet showers—but no such star has been found.

Chapter Seven: Exploring the Oort Cloud—The Final Frontier

The Challenge of Distance

Reaching the Oort Cloud with spacecraft is an extraordinary challenge. Even our fastest spacecraft, Voyager 1, launched in 1977, is only about 160 AU from the Sun as of 2024—barely a fraction of the distance to the inner Oort Cloud. At its current speed, Voyager 1 would take another 300 years just to reach the Oort Cloud’s inner boundary and perhaps 30,000 years to pass through it.

Future Missions and Concepts

While direct exploration remains a distant goal, future technologies may one day allow us to visit the Oort Cloud. Concepts like nuclear-powered propulsion, solar sails, or even laser-driven spacecraft (like Breakthrough Starshot) could shorten the journey.

In the meantime, astronomers continue to study Oort Cloud comets to learn more about this distant realm. Advances in telescope technology and deep-space observation may also help us detect objects in the Oort Cloud directly in the future.

The Oort Cloud and the Edge of the Solar System

Where Does the Solar System End?

The Oort Cloud blurs the line between the Solar System and interstellar space. While the planets, the Kuiper Belt, and even the heliosphere—the bubble-like region dominated by the solar wind—are clearly part of the Sun’s immediate domain, the Oort Cloud exists in a twilight zone. Its objects are still gravitationally bound to the Sun, but they exist in a region influenced by the broader galaxy.

Some astronomers define the Solar System as extending to the outer edge of the Oort Cloud, making it one of the largest known systems in space.

Cosmic Perspective—The Oort Cloud’s Role in Our Place in the Universe

The Oort Cloud isn’t just a distant shell of ice and rock—it’s a window into our past and a key to understanding planetary systems beyond our own. Other stars likely have their own Oort Clouds, formed in similar ways. By studying our own cloud, we can gain insight into the processes that shape solar systems throughout the galaxy.

As we explore further into space, the Oort Cloud will remain a boundary of both scientific discovery and philosophical reflection. It is the last visible trace of the Sun’s domain before we venture into the vast expanse of interstellar space.

Conclusion: The Silent Guardians of the Solar System

Though unseen, the Oort Cloud looms as a silent guardian at the edge of the Solar System. It is both a relic of our cosmic beginnings and a potential harbinger of celestial events that could shape our future. It reminds us of the enormity of the universe and the delicate balance of forces that hold our small corner of space together.

One day, humanity may reach the Oort Cloud, sending robotic explorers—or even human pioneers—to study its icy inhabitants. Until then, it remains an alluring mystery on the edge of the known world, whispering secrets of creation, destruction, and the infinite possibilities that await in the cosmos beyond.