In human society, age-old stereotypes often paint men as daring adventurers and women as careful navigators of risk. From the daredevil acts of early explorers to the popular notion that women are more risk-averse investors, these generalizations shape how we view gendered behavior. Evolutionary psychologists argue that these tendencies have deep roots, shaped by millions of years of adapting to threats and opportunities specific to each sex. But while the story is far more nuanced when it comes to complex human behavior, dramatic differences between male and female behavior are often strikingly clear in the animal kingdom. Now, a groundbreaking study sheds new light on the origins of these differences—by zooming in on some of the tiniest creatures on Earth: worms.

A team of scientists at Israel’s renowned Weizmann Institute of Science has unveiled surprising insights about the brains and guts of male and female roundworms (Caenorhabditis elegans), showing that the males are biologically wired to take life-threatening risks, even when it would be smarter to play it safe. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, offer a fascinating glimpse into the fundamental biological factors that drive differences between the sexes—and hint at surprising parallels between simple worms and complex human beings.

The Risky Business of Being Male—Even for Worms

At the heart of the study lies a question both simple and profound: Why are males often less cautious than females? While cultural and social forces help shape human behavior, the researchers set out to uncover whether deep biological mechanisms might underpin these tendencies, even in simple organisms.

Their organism of choice was C. elegans, a microscopic roundworm barely 1 millimeter long. Despite its tiny size and apparent simplicity, C. elegans has become one of biology’s most powerful model organisms. Its nervous system, composed of a mere 302 neurons (compared to billions in humans), has been fully mapped—down to every synapse. Even better for the researchers, C. elegans sex is determined solely by its genes. There are no hormones or parental influences to complicate matters, making it the perfect living laboratory to study sex-based biological differences.

In this worm world, there are two sexes: males, and hermaphrodites. Hermaphrodites are biologically female but also produce male sex cells, meaning they can self-fertilize or mate with males. This dual capability already hints at differing evolutionary priorities—but how do those priorities shape behavior?

When Food Turns Fatal

The Weizmann team, led by Dr. Meital Oren-Suissa and doctoral student Sonu Peedikayil-Kurien, designed an experiment with an elegant twist of danger. C. elegans feeds on bacteria, but not all bacteria are friendly. One in particular, a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, emits an irresistible smell to the worms, drawing them in. Yet if they succumb to temptation and feast on it, they pay a high price: infection, illness, and often death.

The question was whether male and female worms could learn to avoid this deadly snack.

To find out, the scientists “trained” two groups of worms—males and hermaphrodites—by exposing them to the dangerous bacteria. After this exposure, the worms were given a choice: return to the dangerous bacterium or opt for a safer, less alluring alternative.

The results were stark. The hermaphrodites quickly learned their lesson. Once they experienced illness from their poor food choice, they sniffed out the danger and veered away from it, choosing safety over sensory pleasure. The males? Not so much.

Despite falling ill, the male worms kept crawling back for more. Many became infected. Many died. Only after prolonged exposure and severe consequences did a few males finally seem to learn to avoid the harmful bacteria. By then, the toll had already been taken.

Brains and Guts in Conversation

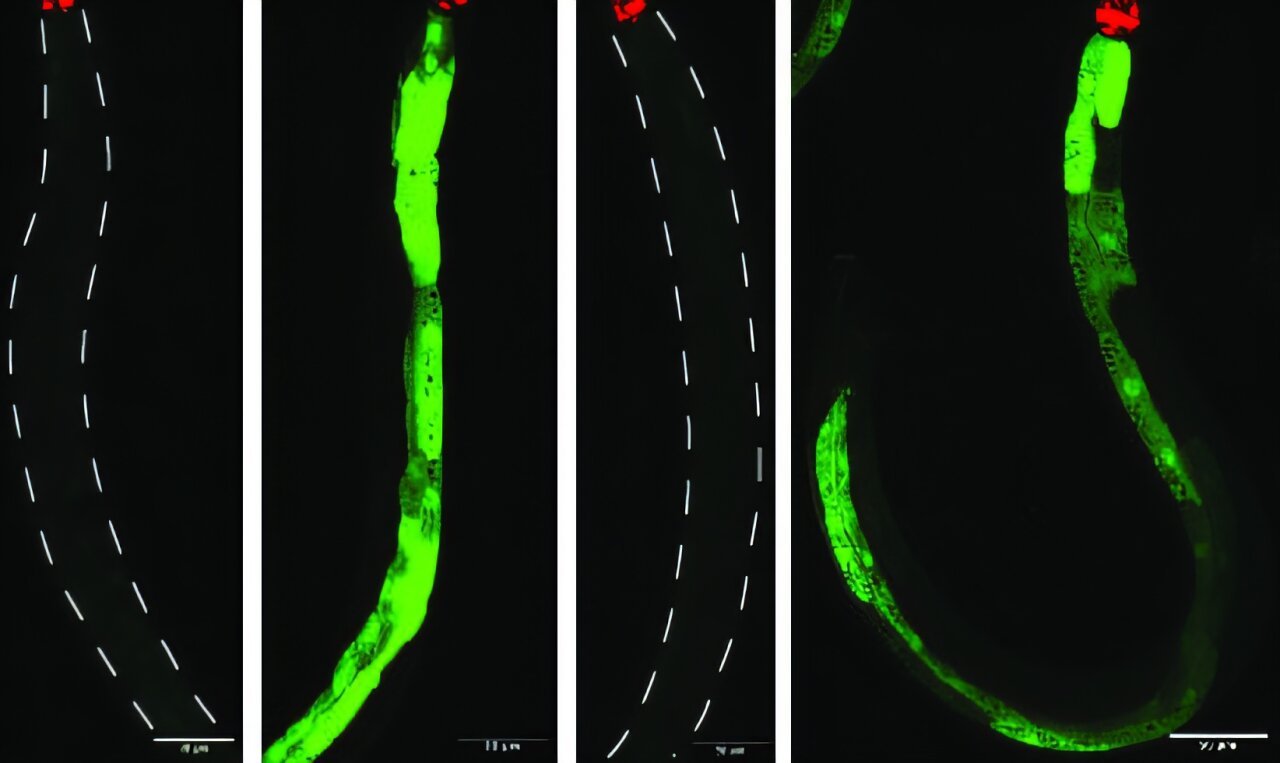

Intrigued by this reckless male behavior, the researchers dug deeper into the worms’ nervous systems. C. elegans has two types of smell-sensitive neurons: one tuned to attraction, the other to repulsion. By tagging these neurons with calcium indicators, the scientists could “watch” them light up as the worms processed odors.

In hermaphrodites, the neurons responsible for repulsion became highly active after exposure to the dangerous bacteria. Their nervous systems effectively “learned” to associate the smell with sickness, triggering an avoidance reaction.

But in males, these repulsion neurons stayed much quieter. Their brains were less responsive to the warning signs their bodies were giving them.

So why the difference?

The researchers decided to play genetic engineer. They reprogrammed hermaphrodites to have male nervous systems—and their ability to learn plummeted. They still encountered danger but failed to make the connection and avoid it later.

Yet flipping the switch in males wasn’t so simple. Giving male worms a female nervous system didn’t make them any smarter. They still had trouble learning.

What tipped the balance was the gut.

The Surprising Power of the Gut-Brain Axis

To truly boost the males’ learning abilities, the scientists had to do more than rewire their brains—they had to give them a female digestive system as well. Only then did the males begin to learn from experience.

This pointed to an extraordinary revelation: the worms’ ability to learn wasn’t just controlled by their nervous systems but by an intimate dialogue between their brains and their guts. Somehow, the digestive system was influencing learning, possibly through signaling molecules known as neuropeptides.

The gut, often called the “second brain” in human studies, seemed to play a direct role in regulating behavior. Even in these simple organisms, the gut-brain connection was critical.

A Single Protein Makes the Difference

The team next set out to pinpoint the molecular players in this biological drama. They focused on a receptor called NPR-5, found in the worms’ sensory neurons. Worms that lacked this receptor—specifically the males—suddenly became much better learners. When the researchers put NPR-5 back into the sensory neurons, the males returned to their old reckless ways.

This suggested that NPR-5 suppresses learning in male worms. Why? The scientists believe it’s tied to reproduction. Male worms will abandon food and safety to seek a mate. Their drive to reproduce seems to override self-preservation instincts.

But there was a twist: if the male worms got to mate during their “training” sessions, their ability to learn improved significantly. With their reproductive urge temporarily satisfied, they became more cautious, shifting their priorities from mating to survival.

In evolutionary terms, this trade-off makes sense. In the wild, male C. elegans have one job: find a mate. Risk-taking pays off if it leads to successful reproduction, even if it shortens their lifespan. Playing it safe doesn’t get them as far.

From Worms to Humans: Shared Biology

Here’s where things get even more fascinating. NPR-5 isn’t unique to worms. A similar receptor exists in mammals, including humans. In mammals, this receptor is activated by a neuropeptide called NPY (Neuropeptide Y), which plays a role in regulating stress, appetite, and emotional responses.

Previous studies have found that female mice have lower levels of NPY than males, making them more sensitive to stress and more responsive to danger cues. Human research suggests a similar trend: women are statistically more prone to anxiety disorders like PTSD, which often involve heightened sensitivity to perceived threats.

Oren-Suissa believes these parallels are more than coincidence. “Our findings in worms suggest that the biological roots of risk-taking and caution could be conserved across evolution,” she says. “While human behavior is vastly more complex, understanding these basic mechanisms helps lay the groundwork for deeper insights.”

What This Means for Us

The Weizmann study offers a thought-provoking glimpse into the ancient biological programming that influences behavior. Even in worms with just a few hundred neurons, clear sex-based differences in learning and risk are hardwired into their biology. These differences appear to be shaped by evolutionary pressures—reproduction versus survival—that still echo in more complex animals.

For humans, the implications are intriguing. Our risk-taking and cautious behaviors are influenced by culture, environment, and personal experience, but this research suggests biology may quietly nudge us toward certain behaviors, too.

And as science continues to explore the gut-brain axis—the powerful communication highway between our digestive systems and our minds—this worm study adds to the growing body of evidence that what happens in the gut can deeply affect how we think, feel, and act.

Final Thoughts: Why Worms Matter

In the end, a microscopic worm might not seem like much. But studies like this one remind us that even the simplest creatures can unlock mysteries about life, learning, and what it means to be male or female. As Oren-Suissa puts it, “By understanding how behavior works at its most fundamental level, we can begin to better understand ourselves.”

And sometimes, it turns out, survival of the fittest depends on knowing when to take a risk—and when to walk away.

Reference: Sonu Peedikayil-Kurien et al, Modulation by NPY/NPF-like receptor underlies experience-dependent, sexually dimorphic learning, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-55950-7