When we gaze up at the night sky, what do we see? Tiny points of light, distant suns burning in the black. Yet we know that many of those stars are not alone. They are hosts to worlds—thousands of them discovered so far, and likely trillions more waiting in the cosmic ocean. But how do we move beyond dots on a telescope and truly know these distant planets? How do we explore the alien skies that hang above these strange new worlds?

The answer lies in a remarkable, fast-evolving branch of science: the study of exoplanet atmospheres.

Peering into an exoplanet’s atmosphere is like opening a window into another world. It tells us about its weather, its chemistry, and even hints at whether something—or someone—might be living there. In the last two decades, astronomers have gone from barely knowing exoplanets existed to analyzing the gases swirling in their skies. And we’re just getting started.

This is the story of how we detect alien atmospheres across unimaginable distances. It’s a tale of technology, ingenuity, and a little bit of cosmic luck.

The Basics: What Is an Exoplanet Atmosphere?

First things first—what are we actually looking for?

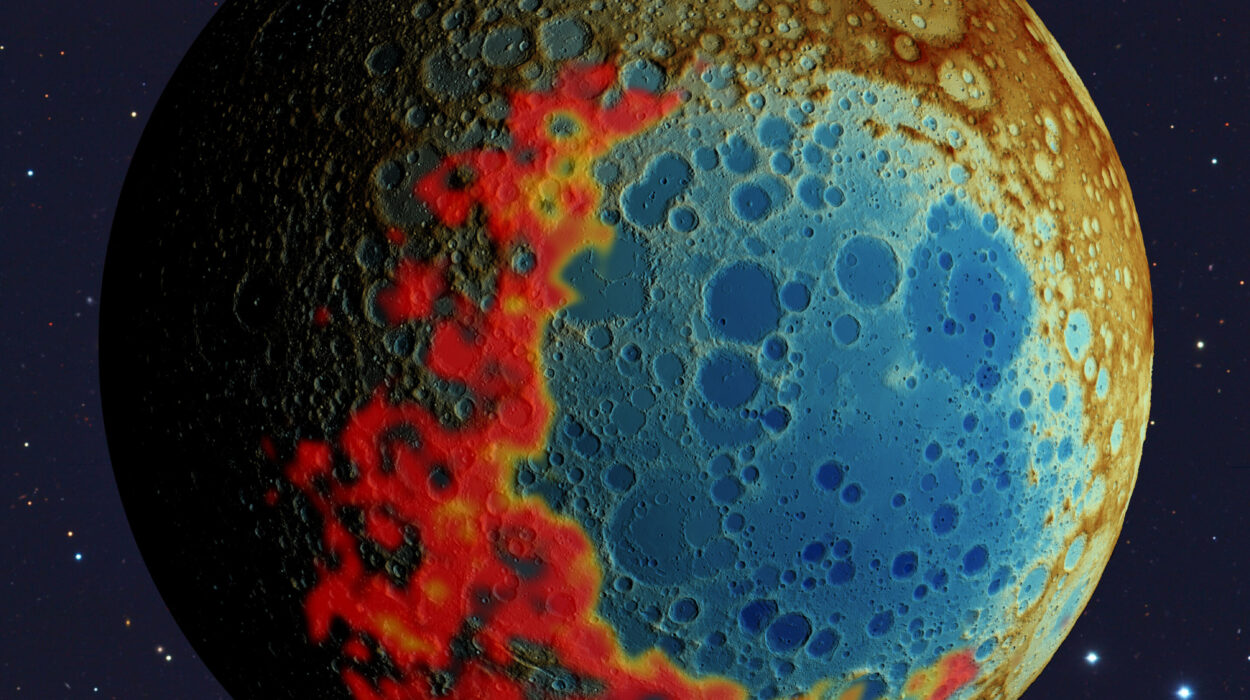

An atmosphere is a layer of gas that clings to a planet, held tight by its gravity. On Earth, our atmosphere is a life-support system: it gives us oxygen to breathe, shields us from dangerous space radiation, and keeps our planet warm. Without it, Earth would be a lifeless rock. The same is true for many other planets.

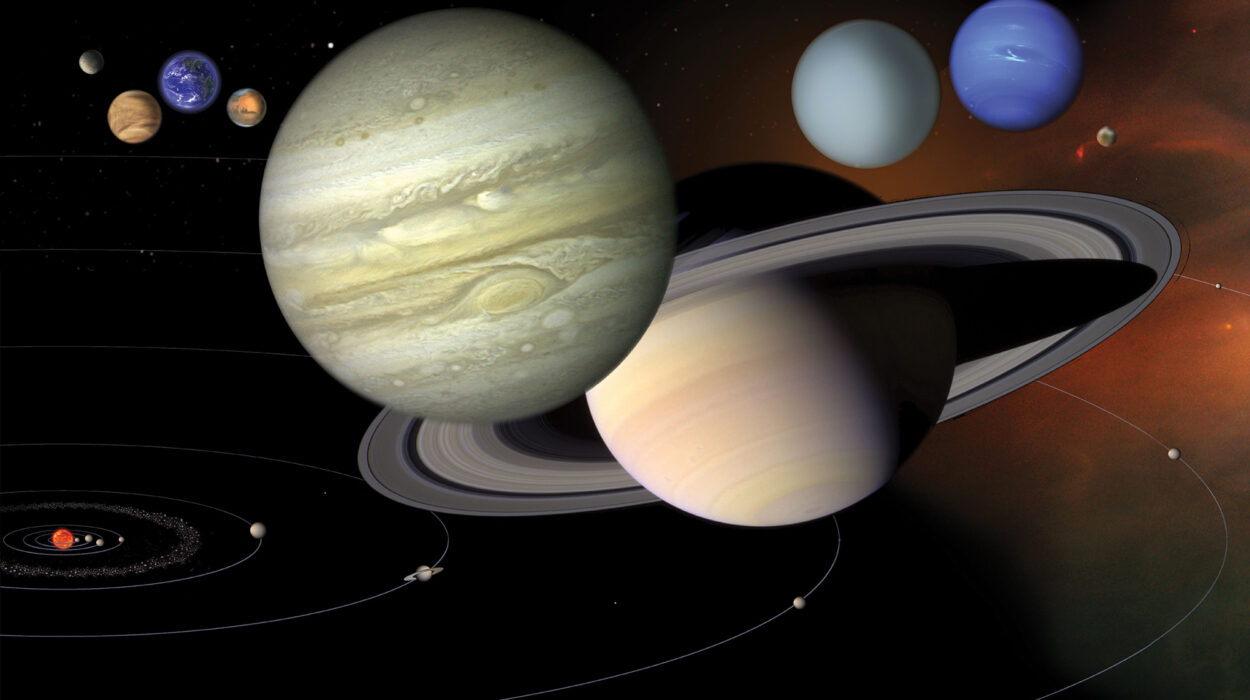

But not all atmospheres are created equal. Some are scorching hot, made of boiling gases like hydrogen or methane. Others are frigid, whisper-thin veils of carbon dioxide. Some planets may have clouds of sulfuric acid, like Venus, or stormy belts of ammonia ice, like Jupiter. Some might even have skies that rain molten glass or iron.

The atmosphere is a planet’s fingerprint. It can tell us whether it’s a scorched hellscape, a frozen wasteland, or something more familiar and life-friendly. But how do we even see an atmosphere that’s light-years away?

The Challenge: Why Is It So Hard to Detect an Exoplanet Atmosphere?

Imagine trying to see a single firefly next to a giant lighthouse—while standing a thousand miles away. That’s what it’s like trying to detect an exoplanet next to its star. Stars are millions of times brighter than the planets orbiting them. Most exoplanets are completely lost in their star’s glare.

And yet, somehow, astronomers have found ways to isolate the faint signals of these alien worlds. The techniques are clever, even a little sneaky. They rely on light, shadow, and some mind-blowing physics.

The Tools of Discovery: How We Study Alien Atmospheres

There are three primary ways scientists can study exoplanet atmospheres today. Each method relies on capturing light—but it’s what we do with that light that makes the magic happen.

1. Transit Spectroscopy: Reading the Shadows

One of the most powerful techniques is called transit spectroscopy.

Imagine an exoplanet passing in front of its star from our point of view. As it crosses, a tiny fraction of the starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere before reaching us. That thin slice of light carries clues about what’s in the air on that distant world.

Certain molecules—like water vapor, methane, carbon dioxide, and oxygen—absorb specific wavelengths of light. By splitting the starlight into its different colors (a technique called spectroscopy), astronomers can spot the telltale signs of those molecules.

The beauty of this method is that we don’t need to “see” the planet directly. We just watch how the light changes when the planet moves in front of its star. It’s a little like shining a flashlight through stained glass and studying the pattern of colors that comes out on the other side.

2. Emission Spectroscopy: Listening to the Glow

If transit spectroscopy lets us study a planet as it blocks its star, emission spectroscopy looks at what happens when the planet moves behind the star.

When a hot planet orbits its star, its dayside is often glowing in infrared light—the heat radiation we can’t see with our eyes. As the planet slips behind the star (in what’s called a secondary eclipse), its light temporarily vanishes from view. By comparing the total light before and after the planet disappears, astronomers can tease out the planet’s thermal signature and even analyze the chemical fingerprints of its atmosphere.

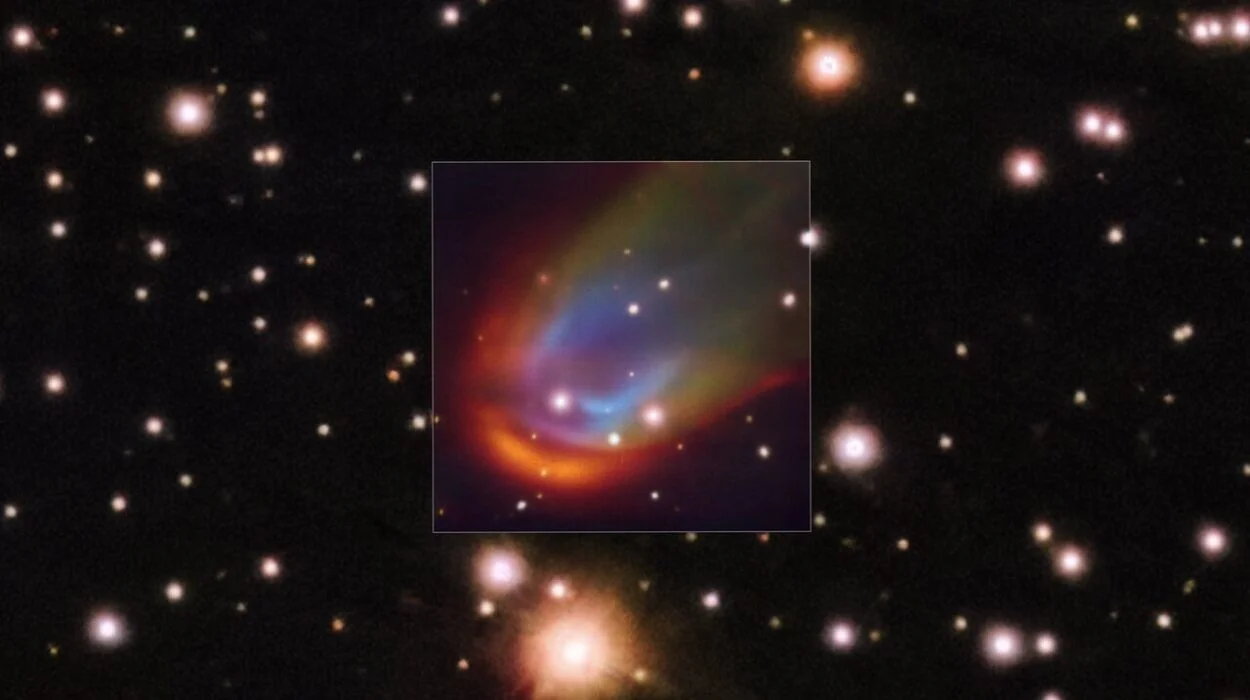

3. Direct Imaging: Taking Pictures of Distant Worlds

This is the dream: snapping a picture of another planet. But it’s incredibly hard because of the brightness problem we mentioned earlier. To do this, astronomers use specialized equipment like coronagraphs (which block out a star’s light) or starshades (giant umbrellas flown in space) to hide the glare and reveal the faint planet nearby.

Once they have a direct image, scientists can perform spectroscopy on the planet’s light, just like we do with transits. Direct imaging is still in its early days, but it holds huge potential—especially for imaging smaller, Earth-like worlds in the future.

What We’ve Found So Far: Exotic Atmospheres and Extreme Worlds

So, what has all this effort uncovered? In short: some seriously wild planets.

Hot Jupiters: Gas Giants Gone Wild

Many of the first atmospheres we studied belonged to hot Jupiters—massive gas giants that orbit very close to their stars. These worlds are blasted with radiation, their skies boiling with extreme winds and scorching temperatures.

For example, WASP-12b is so hot—over 2,500°C (4,500°F)—that its atmosphere is literally being stripped away by its star. Its skies are rich in carbon, possibly containing clouds made of graphite or soot.

Another hot Jupiter, HD 189733b, has clouds of silicate particles. Imagine winds whipping up glass dust, creating storms that could rain molten glass sideways at 5,400 miles per hour. It’s the kind of place where you wouldn’t want to vacation.

Water Worlds and Potentially Habitable Planets

More recently, scientists have detected signs of water vapor on several exoplanets. One of the most exciting discoveries was K2-18b, a planet in its star’s habitable zone—meaning it’s at the right distance for liquid water to potentially exist on its surface.

In 2019, astronomers found water vapor in K2-18b’s atmosphere, a tantalizing hint that this mini-Neptune might be more Earth-like than we thought. While we don’t know yet if K2-18b has oceans or life, it shows us that somewhere out there, the conditions for life might exist.

What’s Next: The Future of Exoplanet Atmosphere Research

We are standing at the beginning of a golden age of exoplanet science. The next few decades promise discoveries that will make today’s findings look like the first scribbles on a blank page.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): Peering Deeper

Launched in late 2021, the James Webb Space Telescope is already revolutionizing our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres. Its powerful infrared instruments are perfect for spotting molecules like carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor—even on smaller, rocky planets.

JWST is giving us the clearest, most detailed views yet of alien skies. It’s already detected complex molecules in the atmospheres of distant worlds, and it may soon search for biosignatures—gases like oxygen or methane that could hint at life.

The Ariel Mission and Other Future Projects

ESA’s Ariel mission, launching in 2029, will study the atmospheres of 1,000 exoplanets. Its goal is to understand how planets form and evolve by analyzing their chemical makeup.

NASA’s LUVOIR and HabEx concepts aim to directly image Earth-like planets and look for signs of habitability—or even life.

The Search for Biosignatures: Are We Alone?

Ultimately, the biggest question is: Are we alone?

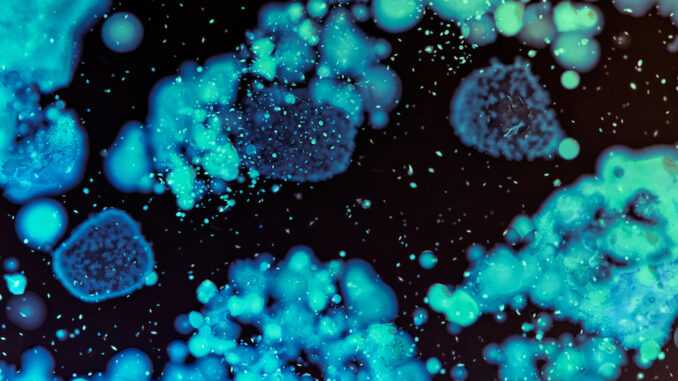

By studying exoplanet atmospheres, scientists hope to find biosignatures—gases or combinations of gases that can’t easily be explained by chemistry alone. On Earth, for example, large amounts of oxygen in the atmosphere are due to photosynthesis. If we find a similar imbalance elsewhere, it could be a sign that something—maybe microbes, maybe more—is alive.

But it won’t be easy. We have to be careful to rule out false positives. Venus has a thick carbon dioxide atmosphere and clouds of sulfuric acid; Mars has methane plumes with uncertain origins. Even Earth, from a distance, might be hard to interpret without context.

Still, the dream remains. The first discovery of life beyond Earth may come not from a spaceship landing on an alien world, but from the careful study of a faint, filtered beam of starlight.

Conclusion: A New Era of Discovery

We live in an extraordinary time. A few centuries ago, we didn’t even know that other planets existed beyond our solar system. Today, we can measure the winds on worlds light-years away. We can sense their skies, feel their heat, and imagine what it would be like to stand under their alien suns.

The study of exoplanet atmospheres is the bridge between science fiction and science fact. With every new discovery, we get closer to answering ancient questions about life in the universe. Somewhere, far beyond our own sky, there may be another planet with clouds, rain, oceans—and life looking up at their stars, wondering if they are alone.

And someday soon, we just might find them.