Water. It shimmers in the oceans of Earth, dances in clouds above mountains, and trickles through every living cell. We humans are, in a very real sense, creatures of water. Life as we know it would be impossible without it. For billions of years, water has carved the valleys, nourished the forests, and whispered beneath the skin of every organism to ever crawl, swim, or fly on our pale blue dot.

But Earth is just one world in a vast and mostly silent cosmos. It’s natural to wonder: Are there other oceans out there? Other rivers under alien skies? Could water—life’s loyal companion—be trickling through strange rocks on distant planets?

For centuries, our ancestors looked up at the stars and imagined distant lands. Today, we are seekers with machines that travel beyond the reach of the sun. The search for water on distant worlds is not just a scientific pursuit. It’s a journey into the heart of our oldest questions: Are we alone? Could life exist elsewhere? And if so, will water be the first signpost we find?

This is the story of humanity’s quest to find water beyond Earth. A tale of wonder, hope, and discovery—a search that is just beginning.

Why Water?

Before we leap toward distant planets and moons, we should ask a basic question: Why is water so important? Why is it the first thing we look for when we search for life in the universe?

Water is unique. It’s often called the “universal solvent,” because it can dissolve more substances than any other liquid. This ability makes it a perfect medium for the complex chemistry of life. Molecules necessary for life can float freely in water, bouncing and interacting in ways that give rise to biology. Water also has a remarkable range of temperatures where it remains liquid—a sweet spot where chemical reactions necessary for life can occur.

Moreover, water’s properties help regulate temperature. It heats and cools slowly, creating stable environments. It can exist as a gas, liquid, or solid within a range of temperatures common on planets, meaning it’s more likely to be found in some form. Ice can float on water’s surface, insulating the liquid beneath and providing shelter for life.

If we find water, we find the possibility of life. It may not be life as we know it, but water is the best place to start.

Our First Clues—Water in the Solar System

Our search for cosmic water began close to home. In the early 20th century, astronomers pointed telescopes at the planets in our solar system. Mars, in particular, fired the imagination. Ancient Martian “canals,” imagined by astronomers like Percival Lowell, were thought to be evidence of intelligent life. Though we later learned those canals were optical illusions, the thirst for discovery remained.

Mars: The Red Planet’s Watery Past

Today, we know that Mars once had water. A lot of it. Robotic rovers like Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance have shown us dried riverbeds, ancient lakebeds, and minerals that can only form in the presence of water.

Billions of years ago, Mars was warmer and wetter. Oceans may have stretched across its northern hemisphere. But something changed. The planet’s atmosphere thinned, and the water vanished—some evaporating into space, some freezing underground.

Even now, traces of water persist. There are polar ice caps made of frozen water and carbon dioxide. Radar data hints at underground lakes of salty water. Seasonal dark streaks on Martian slopes may be evidence of briny water flows, though the jury is still out. If life ever existed on Mars, water was likely its cradle.

Europa: The Ice-Covered Ocean World

Farther out, beyond the asteroid belt, circles Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. From the outside, Europa looks like a frozen world. Its surface is a smooth shell of ice, etched with cracks that suggest movement beneath. But in 1995, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft discovered something astounding: Europa has an ocean beneath its icy crust.

This ocean may contain twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined. It stays liquid thanks to tidal heating, as Europa is constantly squeezed and stretched by Jupiter’s gravity. Hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor could provide energy for life, much like they do in Earth’s deep oceans.

Plumes of water vapor have even been spotted jetting into space from cracks in Europa’s surface. NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission, scheduled for the 2030s, will investigate further. Will we find life swimming in Europa’s alien sea?

Enceladus: Geysers in the Darkness

Saturn’s small moon Enceladus is another ocean world. In 2005, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft flew by and saw something unexpected: towering geysers of water vapor and ice crystals blasting from its south pole. These geysers come from an ocean beneath Enceladus’s frozen crust.

Cassini flew through these plumes and detected water, salts, and organic molecules—the building blocks of life. Enceladus may be one of the most promising places in the solar system to find life. Its ocean is in contact with rock, providing the ingredients for hydrothermal vents—potential underwater oases for alien microbes.

Titan: Lakes of Methane, Rivers of Rain

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, tells a different story. While its surface is too cold for liquid water, Titan has lakes and rivers of liquid methane and ethane. It even rains methane from thick orange clouds. Beneath Titan’s frozen crust, though, scientists believe there is a vast ocean of liquid water mixed with ammonia.

If life exists on Titan, it might not need water in the same way life does on Earth. Some scientists speculate about exotic life forms that could survive in liquid methane. But Titan’s buried water ocean makes it another intriguing world in our search.

The Exoplanet Revolution

For most of human history, the stars were fixed points of light, too distant for us to imagine them as anything else. But everything changed in 1992, when astronomers discovered the first exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars.

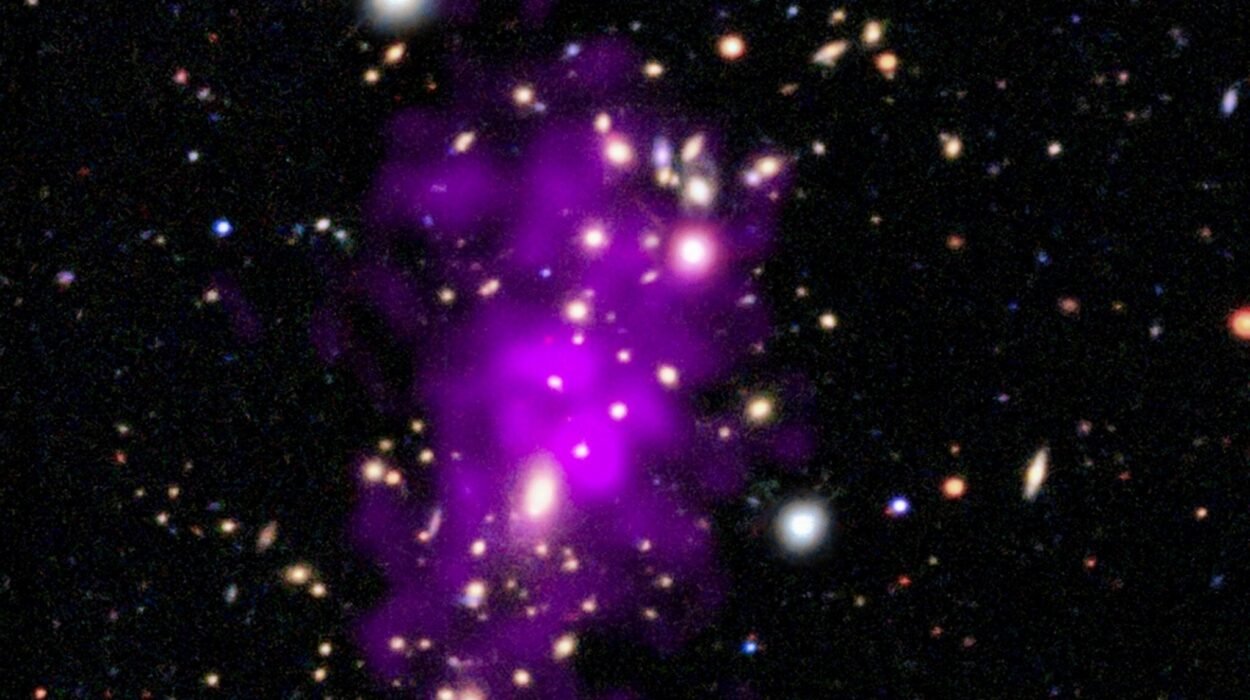

Since then, we’ve found more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets, with new ones added every month. Some are gas giants larger than Jupiter. Others are rocky Earth-sized worlds. They orbit stars like our sun and stars wildly different.

Many of these exoplanets lie in their stars’ habitable zones, where temperatures could allow liquid water on their surfaces. These “Goldilocks” zones are not too hot, not too cold, but just right. So where are we looking, and what have we found?

Kepler and TESS: Planet-Hunting Machines

NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope was a game-changer. Launched in 2009, it stared at a patch of sky, watching thousands of stars for tiny dips in brightness—signs of planets passing in front. Kepler found thousands of candidates, revealing that planets are common, and Earth-sized worlds are plentiful.

Its successor, TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), launched in 2018, surveys nearly the entire sky. TESS focuses on nearby stars, giving us planets we might one day study up close.

TRAPPIST-1: Seven Earth-Sized Worlds

One of the most exciting discoveries came in 2017: the TRAPPIST-1 system. This small, cool star has seven rocky planets, three of them in the habitable zone. These worlds are close enough to us—just 40 light-years away—that future telescopes might study their atmospheres.

Could they have water? Could they host life? TRAPPIST-1 has become a prime target for the next generation of space observatories.

How Do We Find Water on Distant Worlds?

It’s one thing to find a planet. It’s another to know what’s happening on its surface or in its atmosphere. So how do we detect water across the vast emptiness of space?

Spectroscopy: Reading the Cosmic Fingerprint

When a planet passes in front of its star, starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere. Different molecules absorb different wavelengths of light, leaving fingerprints we can detect. Water vapor has a distinct signature in infrared light.

By studying these spectra, we can tell whether a planet’s atmosphere contains water, methane, oxygen, or carbon dioxide—molecules that, together, might suggest life.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

Launched in 2021, JWST is the most powerful telescope ever sent to space. One of its main missions is to study the atmospheres of exoplanets. Already, JWST has detected water vapor in the atmospheres of gas giants and is set to examine rocky planets like those in TRAPPIST-1.

JWST can analyze light with incredible sensitivity, looking for the chemical signs of habitability—or even life.

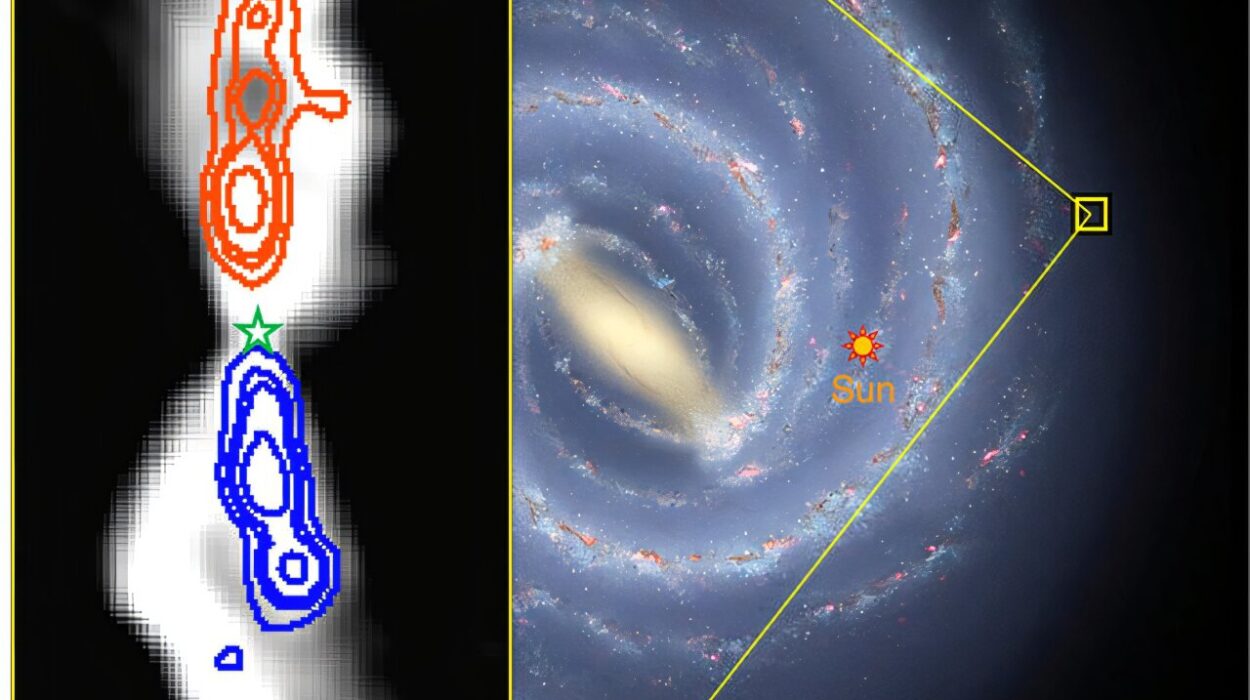

Oceans Without Stars—The Hidden Water Worlds

Not all water worlds orbit stars. Some may wander alone through the galaxy—rogue planets flung from their home systems. Without sunlight, could they still have oceans?

Surprisingly, yes. If these rogue planets have thick atmospheres rich in hydrogen, they could trap heat. Some might have geothermal warmth from radioactive decay in their cores, keeping subsurface oceans liquid.

In our own solar system, Europa and Enceladus are warmed not by sunlight, but by tidal forces. Similar mechanisms could keep rogue ocean worlds warm and wet, even in the darkness between stars.

These hidden water worlds may outnumber the planets we find around stars. The galaxy could be teeming with life in places we never expected.

What If We Find Life?

The discovery of water is thrilling. But what happens if we find life—alien life? Would it be microbes, swimming in subsurface oceans, or something more complex? Would it be DNA-based, like life on Earth, or something utterly foreign?

Finding life elsewhere would answer one of humanity’s greatest questions. It would tell us we are not alone. It would also raise ethical and philosophical questions: Do we have the right to explore or even colonize worlds where life already exists?

If we found evidence of life, it would change everything. Our religions, our philosophies, our sense of place in the universe would be transformed.

The Future of the Search

The search for water on distant worlds is just beginning. Over the next few decades, new missions will expand our reach.

Europa Clipper and Dragonfly

NASA’s Europa Clipper, launching in the 2030s, will fly by Europa dozens of times, mapping its surface and analyzing its plumes. It will search for signs of life beneath the ice.

Dragonfly, a drone mission to Titan, will arrive in the 2030s. It will fly through Titan’s thick atmosphere, studying its chemistry and searching for prebiotic compounds.

LUVOIR and HabEx

Future space telescopes like LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor) and HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Observatory) are being planned. They could directly image Earth-like planets and analyze their atmospheres in detail, searching for water—and life.

Human Exploration

One day, humans may walk on Mars, drill through Europa’s ice, or sail on Titan’s methane seas. The search for water may lead us to new homes beyond Earth.

Conclusion: A Thirst That Drives Us Forward

Water is more than a molecule. It’s a symbol of life, a sign of hope, and a reason to explore. As we search the stars for water, we are searching for ourselves—our origins, our place in the cosmos, and our future.

The universe is vast, and water is plentiful. Oceans may stretch beneath icy shells, rivers may flow beneath alien suns, and clouds may drift above distant worlds.

The search for water is the search for life. And the search for life is the search for connection.

We are not just looking outward. We are listening for an answer to a question that has echoed since the first human looked up at the stars and wondered: Are we alone?

The End (or the Beginning…)