Every morning, like clockwork, it rises—brilliant, golden, and life-giving. We see it crest the horizon, feel its warmth on our skin, watch it cast long shadows, and ignite the sky with reds and oranges as it sinks again each evening. The Sun has been humanity’s companion since time began. Civilizations have worshipped it, charted their lives by it, and feared its disappearance during eclipses. But how well do we really know our star?

Despite being the most familiar celestial body in our sky, the Sun hides secrets beneath its blazing surface. Secrets that scientists have only recently begun to uncover. It is a seething ball of nuclear fire, a churning sea of plasma, a factory of elements, and a source of both life and destruction.

This is the story of our star—the Sun. A story of creation and cataclysm, of fiery tempests and invisible winds, of ancient myths and cutting-edge science. It’s a story still being written, by solar physicists, spacecraft, and observatories around the world. And it’s a story that affects every one of us, in ways both obvious and profound.

A Star is Born

Four and a half billion years ago, in a quiet corner of the Milky Way, a cloud of gas and dust hung in space. Cold, dark, and vast beyond imagining, this nebula floated aimlessly—until something stirred it.

Some scientists believe a nearby supernova exploded, sending shockwaves through the cloud. Others think gravitational instabilities began to tug and pull. Either way, the gas and dust began to collapse inward, slowly but inevitably. Gravity gathered the matter tighter and tighter, until the pressure at the heart of this collapsing cloud soared.

Temperatures climbed. At first, they were merely hot. Then they became unimaginably hot. Eventually, the core of this forming mass reached a critical point. Hydrogen atoms, under crushing pressure and heat, began to fuse.

This was the birth of our Sun. Nuclear fusion ignited. Hydrogen atoms slammed together with such force that they formed helium, releasing staggering amounts of energy in the process. That energy radiated outward as light and heat, pushing back against the crushing pull of gravity.

The Sun reached equilibrium. It was alive.

The Physics of Fire

At its core, the Sun is a massive nuclear reactor. But unlike the reactors on Earth, there are no steel walls or safety valves to contain it—only gravity, squeezing the star’s heart with relentless force.

The core, where fusion occurs, burns at a mind-melting 15 million degrees Celsius. Every second, it fuses about 600 million tons of hydrogen into helium. In the process, around 4 million tons of mass vanish, converted into energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E=mc². That energy takes the form of photons—particles of light—and begins a slow, arduous journey outward.

It’s an almost unimaginable journey. A photon produced in the Sun’s core takes, on average, 100,000 to a million years to reach the surface. Inside the Sun’s radiative zone, photons are constantly absorbed and re-emitted by atoms, zigzagging randomly in a maddeningly slow crawl toward freedom.

Eventually, they reach the convection zone—the outer 30% of the Sun’s interior. Here, the energy is transported by giant columns of hot plasma, which rise toward the surface, cool, and then sink again. It’s a boiling, churning chaos of movement, like an unimaginably vast pot of water on an equally unimaginable stove.

Finally, the energy reaches the photosphere—the visible “surface” of the Sun, though it’s not a solid surface at all, but a thin layer of gas about 500 kilometers thick. From here, light finally escapes into space, traveling at 300,000 kilometers per second.

It takes just over eight minutes for sunlight to reach Earth, after a journey that may have begun a million years ago in the heart of the Sun.

Surface Drama—Sunspots, Flares, and Filaments

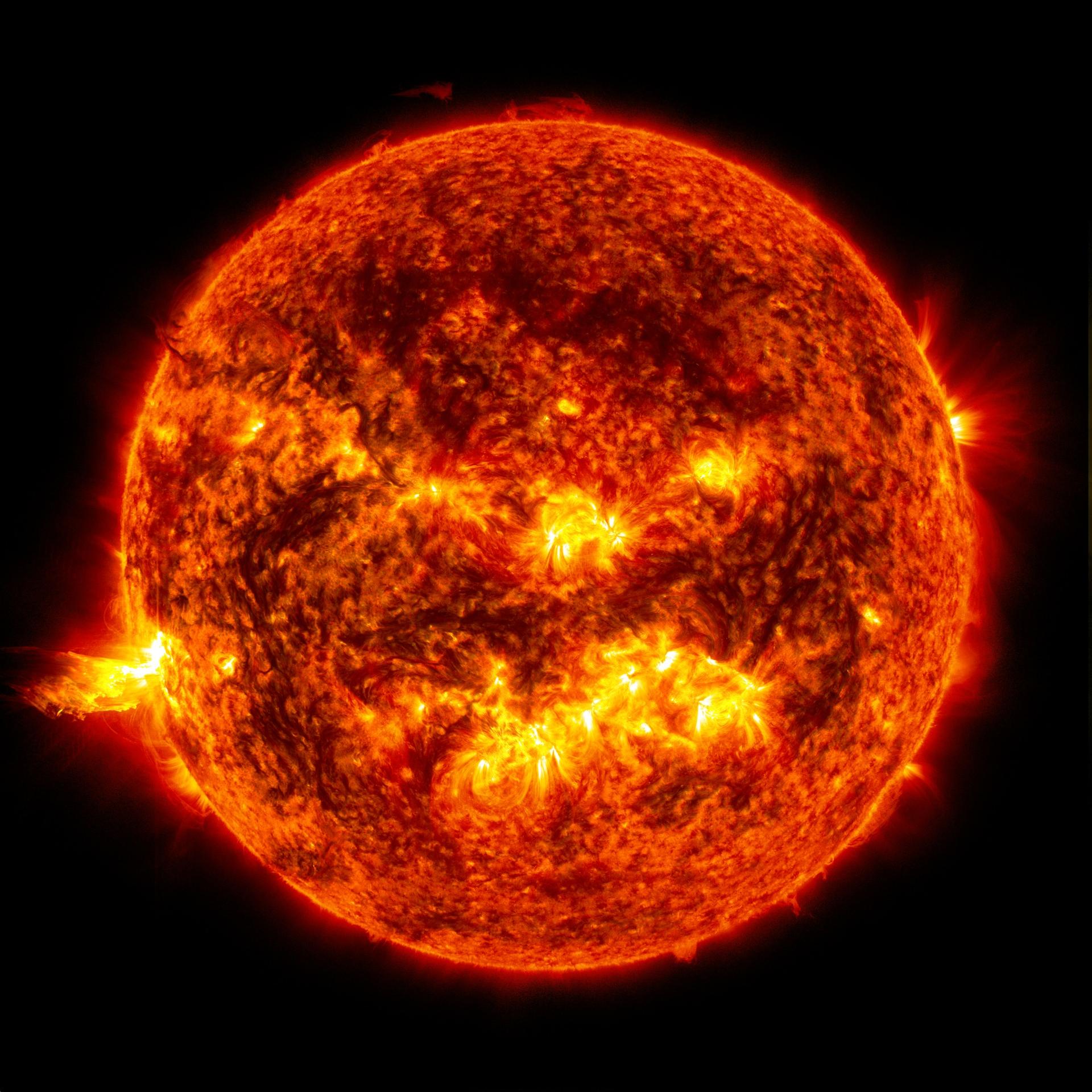

The Sun’s surface may look smooth and uniform from Earth, but it’s anything but. Zoom in, and you’ll see a restless landscape of bright granules and dark patches. These granules are convection cells—huge bubbles of rising hot plasma about 1,000 kilometers across, each lasting about 10 minutes before disappearing.

But the most dramatic features on the surface are sunspots—dark, cooler regions often larger than Earth itself. Sunspots form where the Sun’s magnetic field twists and coils, bursting through the photosphere in tangled knots. These magnetic fields suppress convection, lowering the temperature in these regions by a few thousand degrees.

Sunspots often appear in pairs or groups, and they’re the source of some of the Sun’s most explosive behavior. Alongside sunspots, vast arcs of plasma called prominences stretch thousands of kilometers above the surface. Some of these prominences are stable, lasting for weeks. Others erupt violently.

Then there are solar flares—sudden, intense releases of energy caused by the snapping and reconnecting of magnetic field lines. Flares release bursts of radiation that can be detected across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays.

The most violent outbursts are coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—gigantic bubbles of solar plasma and magnetic fields hurled into space. A CME aimed at Earth can trigger geomagnetic storms, disrupting satellites, damaging power grids, and lighting up the night sky with breathtaking auroras.

The Sun is not a calm star. It’s a stormy, seething engine of magnetic fury.

The Solar Atmosphere—Layers of Mystery

Above the photosphere lies the chromosphere, a thin layer of the Sun’s atmosphere only visible during solar eclipses or with special instruments. The chromosphere is where the temperature begins to climb again, defying expectations. Instead of cooling as you move away from the Sun’s surface, it heats up.

And above the chromosphere lies the corona—a halo of plasma that extends millions of kilometers into space. The corona is ethereal and faint, but during a total solar eclipse, it shines like a ghostly crown around the blackened disk of the Moon.

Here lies one of the Sun’s greatest mysteries: the coronal heating problem. The corona is hotter than the Sun’s surface—millions of degrees hotter. Scientists have proposed various mechanisms for this inexplicable heating, including magnetic reconnection and waves of energy called Alfvén waves, but the answer remains elusive.

The corona is also the birthplace of the solar wind—a constant stream of charged particles that flows outward from the Sun at speeds of up to 800 kilometers per second. The solar wind shapes the heliosphere, a vast bubble that extends beyond the orbit of Pluto, enveloping the entire solar system.

Earth’s magnetic field shields us from the solar wind’s worst effects, but the wind interacts with our magnetosphere to create the auroras—dancing lights in the polar skies, as solar particles slam into atoms in our atmosphere, causing them to glow.

Space Weather—The Sun’s Influence on Earth

The Sun may be 150 million kilometers away, but its influence is felt intimately on Earth. We live within its extended atmosphere, and when the Sun gets feisty, so does our planet.

Solar flares and CMEs can trigger space weather events that disrupt modern technology. In 1859, a massive solar storm known as the Carrington Event produced auroras visible as far south as the Caribbean and caused telegraph systems to spark and fail. If such an event occurred today, it could knock out power grids, cripple satellites, and wreak havoc on global communications.

Modern satellites monitor the Sun constantly, giving us early warning of potential space weather threats. Agencies like NASA and the European Space Agency have spacecraft like SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory), STEREO (Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory), and the Parker Solar Probe watching the Sun’s every move.

But space weather isn’t all doom and gloom. It’s also a source of scientific wonder. By studying how the solar wind interacts with planetary magnetic fields, we learn about the protective shields of other worlds—and what happens when they’re absent, as on Mars, where the atmosphere was stripped away by the solar wind.

Exploring the Sun—Probes, Observatories, and Missions

For centuries, astronomers studied the Sun with nothing more than telescopes and careful observation. Galileo was the first to observe sunspots systematically, and he paid a price for his curiosity—he damaged his eyesight.

Today, our tools are far more sophisticated. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) captures high-resolution images of the Sun in multiple wavelengths, revealing its complex magnetic dance. The Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, is humanity’s boldest attempt to touch the Sun. It dives closer to the Sun than any spacecraft before, braving temperatures of over 1,300 degrees Celsius and gathering data on the solar wind and corona.

Then there’s the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter, which gives us unprecedented views of the Sun’s poles—regions critical to understanding the solar magnetic cycle.

Ground-based observatories like the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii capture details as small as 30 kilometers across on the solar surface, revealing the Sun’s granules and magnetic fields with breathtaking clarity.

These missions and instruments are unlocking the Sun’s secrets, answering old questions and raising new ones. Why does the Sun’s magnetic field flip every 11 years? What drives the solar cycle? How does the solar wind accelerate to such incredible speeds?

The Solar Cycle—A Pulsing Heartbeat

The Sun is not static. It goes through an 11-year cycle of activity, swinging between solar minimum and solar maximum. During solar maximum, sunspots, flares, and CMEs are frequent. During solar minimum, the Sun’s surface may go weeks without a single spot.

This cycle is driven by the Sun’s magnetic field, which becomes twisted and tangled over time. Eventually, the magnetic field flips—north becomes south, and south becomes north. This flipping drives the waxing and waning of solar activity.

The solar cycle affects everything from satellite operations to climate patterns on Earth. During periods of high solar activity, the Sun’s increased ultraviolet radiation heats Earth’s upper atmosphere, expanding it and increasing drag on satellites. Radio communications are affected, GPS signals can be disrupted, and the increased solar wind can enhance auroras.

Understanding the solar cycle helps us prepare for space weather events—and also gives us insight into the behavior of other stars. Our Sun’s cycles may be relatively mild; other stars experience “superflares” that dwarf anything we’ve observed from our own star.

The Sun and Life on Earth

Without the Sun, life on Earth would be impossible. Its light fuels photosynthesis, driving the food chain. Its warmth keeps our oceans liquid and our climate stable. The Sun’s energy even played a role in shaping Earth’s atmosphere.

But the Sun is also a source of danger. Its ultraviolet radiation can damage DNA, causing sunburn and increasing the risk of skin cancer. Thankfully, Earth’s ozone layer absorbs much of this radiation, acting as a shield.

Over geological time, variations in the Sun’s energy output have influenced Earth’s climate. Periods of low solar activity, such as the Maunder Minimum in the 17th century, coincided with the Little Ice Age, a time of cooler global temperatures. Scientists continue to study how solar variability affects Earth’s climate today.

The Sun’s life-giving energy is a delicate balance. Too much or too little, and life as we know it could not survive.

The Future of the Sun

The Sun has been shining for about 4.6 billion years. It’s about halfway through its life as a main-sequence star. For another 5 billion years, it will continue fusing hydrogen into helium in its core, maintaining its balance between gravity and radiation.

But eventually, the hydrogen will run out. The core will contract, heating up and igniting a new phase of fusion—helium into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen. The outer layers of the Sun will expand, engulfing Mercury and Venus, and perhaps even Earth. The Sun will become a red giant.

In its final act, the Sun will shed its outer layers into space, creating a glowing shell called a planetary nebula. The core that remains will cool and shrink into a white dwarf—a dense, Earth-sized ember that will slowly fade over trillions of years.

This is the destiny of our Sun—a gentle end, compared to the violent deaths of more massive stars that explode as supernovae.

Epilogue: Our Place in the Sun

We are children of the Sun. Every atom of our bodies—every molecule of water, every breath we take—is connected to our star. The Sun forged the energy that powers life, and stars like it created the heavier elements that make up the Earth itself.

Understanding the Sun is not just an exercise in science. It’s a journey to understand our origins and our future. As we gaze up at the sky, we are reminded that we orbit a star—a fiery, dynamic, and magnificent star. A star whose secrets we are only beginning to uncover.

And as we continue to study the Sun, we gain not only knowledge but also a profound sense of wonder. The Sun is more than a glowing orb in the sky. It is our star. And it still has many stories left to tell.

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.