In 2015, an archaeological excavation at the former Animal Husbandry Center of Nescot College in Ewell, Surrey, uncovered a remarkable and perplexing discovery. Beneath the ground lay an ancient Roman quarry pit, its layers holding a fascinating story of ritual, sacrifice, and cultural traditions in Roman Britain. Among the most striking findings was an astonishing number of dog remains—5,436 bones belonging to at least 140 individual dogs—making it one of the largest dog assemblages ever discovered in Roman Britain.

This discovery, analyzed by Dr. Ellen Green and published in the International Journal of Paleopathology, raises intriguing questions about the role of dogs in Roman and Romano-British religious practices. Were these animals beloved companions, ritual offerings, or symbols of deeper spiritual significance?

The Role of Dogs in Roman and Romano-British Society

Dogs occupied an essential place in the daily life of Romans and their British counterparts. In practical terms, they were hunters, herders, guardians, and companions. Roman Britain, in particular, was famous for its hunting dogs, which were so highly valued that even Greek geographer Strabo noted them as a chief export of Britannia.

However, beyond their functional roles, dogs held significant symbolic and religious meaning. In Roman mythology, dogs were associated with various deities and spiritual concepts, particularly in their connection to the underworld, fertility, healing, and protection.

For instance, Pluto (the god of the underworld) was often depicted alongside a guardian dog, while Hecate, the goddess of magic and the moon, was frequently associated with spectral hounds. The belief that dogs could serve as protectors of souls or guides to the afterlife may explain their presence in ritual contexts.

The Nescot Ritual Shaft: A Unique Archaeological Find

The excavation of the Nescot site revealed a 4-meter-deep oval shaft, dating to the late first and early second centuries CE. This feature, originally a Roman quarry pit, had been repurposed into a deposit filled with faunal remains, human remains, coins, pottery, metal artifacts, and even gaming tokens.

Archaeologists identified three distinct phases of the shaft’s use:

- The first two phases contained the majority of the faunal remains, including an overwhelming number of dog bones.

- The third phase saw a significant decrease in ritual deposits, transitioning into what appeared to be a more mundane refuse pit.

The sheer volume of dog remains in the earlier phases is unusual. Despite the common presence of dogs at Romano-British sites, they typically account for only 2–4% of animal remains. The Nescot shaft, however, was composed of 10,747 animal bones, with more than half belonging to dogs—an unprecedented proportion.

What the Bones Reveal: Health and Care of the Nescot Dogs

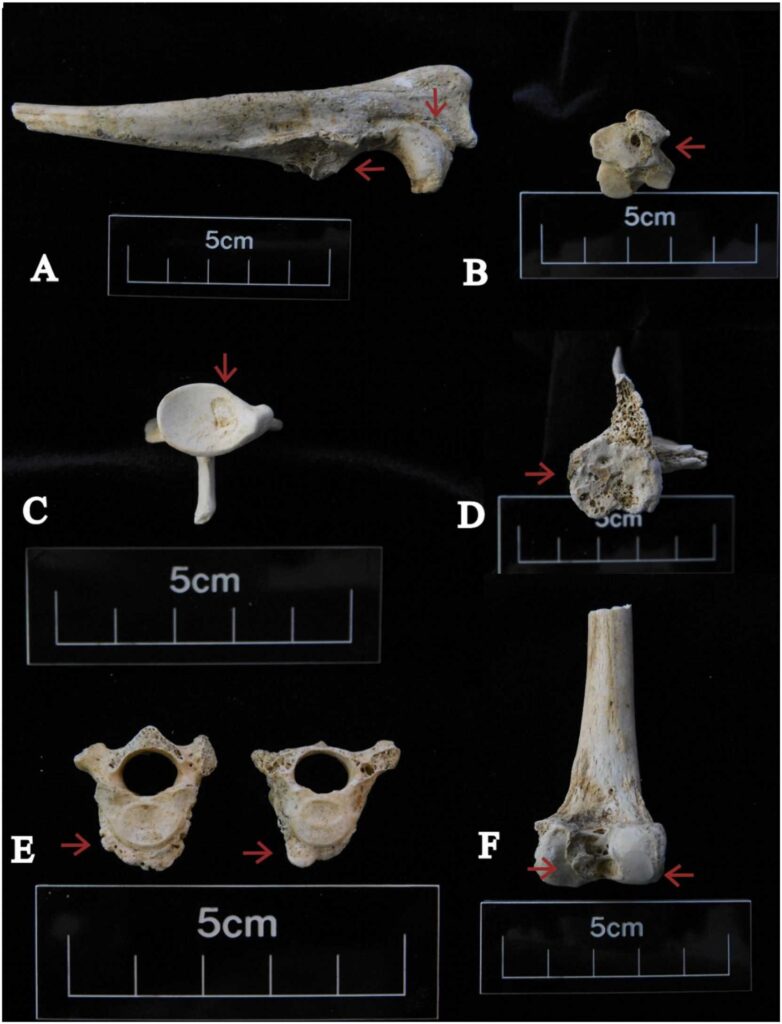

Dr. Green’s analysis provided valuable insights into the lives of the dogs before their deposition. The assemblage represented a diverse range of dogs, though the majority were small breeds. Some displayed chondrodysplasia, a genetic condition causing disproportionately short limbs relative to body size—similar to modern corgis. Additionally, historical records indicate that Romans kept dogs resembling the modern Maltese, which aligns with the smaller dogs found at Nescot.

Interestingly, these dogs showed signs of care and longevity. Many had age-related conditions such as:

- Spondylosis deformans – a degenerative spinal disease.

- Ossified costal cartilage – a condition where rib cartilage turns to bone with age.

- Fibula-tibia fusion – a sign of advanced age in some specimens.

The presence of older dogs, alongside the relative lack of trauma or butchery marks, suggests they were not killed for food or fur. However, some specimens did exhibit scapular lesions, which are often linked to excessive exercise, malnutrition, or genetic factors. Given their small size, strenuous physical labor is unlikely, leading researchers to consider inbreeding as a potential cause.

Were the Dogs Ritual Offerings?

The presence of human remains, combined with comparisons to similar ritual shafts in Roman Britain, suggests that the Nescot dogs were not simply discarded pets but were part of a ceremonial or sacrificial practice.

Dr. Green hypothesizes that cultural selection played a role in their inclusion. “The Romans had specific rules about what types, colors, ages, and sexes of animals were appropriate for sacrifice to different gods,” she explains. “It’s likely that these dogs were chosen based on such cultural criteria.”

This interpretation is reinforced by comparisons with other sites:

- At urban settlements, sacrificed dogs were often stray or mixed-breed animals.

- At ritual-specialized sites, offerings tended to be healthier, well-cared-for individuals—like the Nescot dogs.

The Transition from Ritual to Rubbish

As time progressed, the shaft’s use changed. In the third phase, the number of faunal remains dramatically decreased, and the few that were present bore clear signs of butchery, such as chop marks and fresh breaks—indicating they were used for food rather than ritual purposes.

By the early second century CE, all deposits—ritual or otherwise—into the shaft ceased entirely. This transition suggests that the site, once considered sacred, gradually lost its religious significance and was eventually abandoned as a place of deposition.

The Broader Implications of the Nescot Discovery

The Nescot ritual shaft challenges our understanding of Roman and Romano-British religious practices. It raises important questions:

- Were the dogs sacrificed in a specific ritual, and if so, which deity was being honored?

- Why were small, well-cared-for dogs preferred for this practice?

- Did the presence of human remains indicate a more complex ritual involving both human and animal sacrifice?

While definitive answers remain elusive, the evidence strongly suggests that these dogs played a meaningful role in religious or spiritual practices. The find also underscores the blending of Roman and native British traditions, as the burial of dogs in ritual contexts has deep roots in pre-Roman Iron Age Britain.

Conclusion

The Nescot ritual shaft stands as one of the most significant and enigmatic archaeological discoveries of Roman Britain. The thousands of dog bones recovered from the site provide a glimpse into the complex interplay of religion, ritual, and human-animal relationships in the ancient world.

Though we may never fully understand the precise motivations behind these deposits, the research by Dr. Ellen Green offers a compelling narrative: these dogs were not merely discarded, but carefully selected, revered, and ritually deposited in a practice that blended Roman and indigenous spiritual traditions.

Their presence in the shaft serves as a haunting yet fascinating testament to how deeply intertwined animals were with the sacred and the supernatural in ancient societies. The mystery of the Nescot dogs continues to captivate archaeologists and historians alike, reminding us that the past holds secrets waiting to be uncovered—bone by bone.

Reference: Ellen Green, The pathology of sacrifice: Dogs from an early Roman ‘ritual’ shaft in southern England, International Journal of Paleopathology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpp.2025.02.005