Step outside and look around. Whether you’re in the heart of a bustling city, the edge of a dense forest, or walking along a quiet beach, you’re standing in the midst of an ecosystem. It may be lush and green, dry and sparse, filled with the buzz of insects or the hum of machines. But the truth remains: ecosystems are everywhere, surrounding us, supporting us, shaping our existence in ways we rarely notice but deeply rely on.

An ecosystem isn’t just a forest full of trees or a pond with fish. It is a living, breathing network of interactions between organisms—plants, animals, fungi, bacteria—and their physical environment. This network is fueled by the flow of energy and nutrients, driven by sunlight and cycles of matter. Ecosystems are at once incredibly complex and elegantly balanced. They are the stage and the actors, the rules and the improvisation, the container of life and the force that shapes it.

A Definition Rooted in Interdependence

The term “ecosystem” was first coined by British ecologist Arthur Tansley in 1935. He sought a term that described not just the living organisms (what scientists call the “biotic” components) but also the non-living environment (“abiotic” factors) and how the two interact. His idea was revolutionary for its time—it broke down the barrier between life and environment, treating them as two halves of a single, dynamic system.

At its core, an ecosystem is defined as a community of living organisms interacting with one another and with their physical environment in a particular area. This definition, while simple, unlocks a universe of complexity. It means that every bird singing in a tree, every worm burrowing in the soil, every molecule of water evaporating under the sun—all are part of a tightly interwoven fabric of relationships that keep the whole system functioning.

A Web of Life and Energy

To truly understand what an ecosystem is, we must follow the flow of energy. All life depends on energy, and in most ecosystems, that energy begins with the sun. Plants, through photosynthesis, capture solar energy and convert it into sugars. These plants, known as primary producers, form the base of the food chain.

Herbivores—like deer, insects, or grazing animals—eat the plants. Carnivores eat the herbivores. Decomposers, like fungi and bacteria, break down dead organisms and return nutrients to the soil. This chain of consumption and recycling is not a straight line but a complex web, where everything is connected to everything else.

This flow of energy is what keeps an ecosystem alive. It powers the growth of trees, the migration of animals, the flowering of plants, the very processes of life itself. And crucially, it is not just about who eats whom—it’s about balance. Too many predators, and prey populations crash. Too few decomposers, and nutrients stop cycling. Ecosystems thrive on equilibrium.

Diversity: The Strength of an Ecosystem

If there’s one word that lies at the heart of ecosystem health, it is diversity. Biodiversity—the variety of species in a given area—acts as a kind of ecological insurance. With more species come more functions, more roles, more resilience. A forest with hundreds of tree species, for example, is more likely to survive disease outbreaks than one dominated by a single species.

But biodiversity isn’t just about the number of species; it’s also about the variety of roles they play. Some plants fix nitrogen from the air, enriching the soil. Certain animals disperse seeds. Others act as pollinators, predators, prey. The more diverse the players, the richer and more stable the performance.

Humans, often unknowingly, depend on this diversity. From the crops we grow to the air we breathe, the medicines we use to the climate that sustains us—biodiversity underpins it all. Every lost species is not just a tragedy for conservationists—it’s a blow to the intricate machinery of the ecosystem.

Ecosystems Aren’t Static—They Evolve

One of the most fascinating truths about ecosystems is that they are never truly still. They are in a constant state of flux, adapting to changes in climate, disturbances, species migration, and even evolution itself. Ecosystems grow, shrink, recover, collapse, and transform.

This process of change is often driven by what ecologists call succession. Imagine a bare patch of land—perhaps created by a volcanic eruption or a retreating glacier. Over time, pioneer species like lichens and mosses colonize it. These are followed by grasses, shrubs, and eventually trees. Animals arrive. Soil deepens. The system becomes more complex. Over decades or centuries, what started as a barren landscape becomes a rich, thriving ecosystem.

Even established ecosystems can undergo dramatic shifts. A forest fire may seem like destruction, but it often clears the way for renewal. Nutrients are returned to the soil, seeds germinate, species adapt. Ecosystems are not fragile—they are dynamic and, often, surprisingly resilient.

Types of Ecosystems: From Micro to Global

Ecosystems exist on every scale imaginable. A single rotting log can host an ecosystem of fungi, insects, and microbes. A pond teems with fish, algae, and aquatic plants, all bound together by their watery home. A desert, though seemingly barren, contains a finely tuned system of life adapted to harsh extremes.

On a larger scale, ecosystems blend into biomes—global-scale ecosystems like tundras, grasslands, rainforests, and oceans. Each biome contains many smaller ecosystems, shaped by local conditions: temperature, rainfall, altitude, latitude, and geography.

Even cities, often thought of as ecological deserts, are ecosystems. Urban ecology is a growing field of study that examines how humans, wildlife, vegetation, air, and infrastructure interact in urban environments. From the squirrels in parks to the microbes in sewers, cities are pulsing ecosystems in their own right.

Humans as Ecosystem Engineers

We often think of ourselves as separate from nature, but humans are deeply embedded in ecosystems—and increasingly, we shape them. Agriculture transformed wild ecosystems into farmland. Cities paved over wetlands and grasslands. Dams, highways, deforestation, pollution—all have ripple effects on ecosystems worldwide.

Yet humans are not merely destroyers. We are also stewards, capable of nurturing and restoring ecosystems. Indigenous peoples have long managed ecosystems sustainably, understanding the subtle interplay of species and seasons. Today, conservationists and ecologists work to replant forests, restore wetlands, protect coral reefs, and bring species back from the brink of extinction.

We are ecosystem engineers—whether intentionally or not. The question is not whether we will impact ecosystems, but how.

Ecosystem Services: Nature’s Gift to Humanity

Perhaps the most compelling reason to care about ecosystems is what they give us. Ecosystem services are the benefits that humans derive from healthy ecosystems. These services are often invisible but essential. They include:

- Provisioning services like food, water, timber, and medicines.

- Regulating services like climate regulation, flood control, and disease suppression.

- Supporting services like nutrient cycling, soil formation, and photosynthesis.

- Cultural services like recreation, spiritual inspiration, and aesthetic value.

Without healthy ecosystems, human civilization would unravel. Imagine a world without pollinators—our food system would collapse. Without forests, carbon would overwhelm the atmosphere. Without wetlands, floods would devastate cities. We are, in every sense, dependent on ecosystems.

The Fragility of the Balance

While ecosystems are resilient, they are not invincible. Human activity—especially in the past two centuries—has put enormous pressure on natural systems. Deforestation, overfishing, pollution, invasive species, habitat destruction, and climate change have pushed many ecosystems to the edge.

Coral reefs are bleaching due to rising temperatures. Rainforests are being cleared at alarming rates. Biodiversity is plummeting. Ecosystems that once thrived are becoming ghostlands—stripped of life, function, and balance.

The consequences of this degradation are not distant or abstract. They are felt in collapsing fisheries, extreme weather events, rising food insecurity, and the spread of zoonotic diseases. The Earth’s warning signs are clear: when ecosystems fail, so do we.

The Hope of Restoration

Despite the damage, there is hope. Ecosystems can recover—sometimes remarkably quickly—if given the chance. Abandoned farmlands can rewild. Rivers can run clean again. Species can return. The science of restoration ecology is dedicated to this mission: bringing ecosystems back to health.

Reforestation projects in the Amazon, coral gardening in the Great Barrier Reef, prairie restorations in North America—these are just a few examples of how humans are working to heal the planet. Every ecosystem restored is a step toward a more resilient, livable future.

Crucially, restoration isn’t just about nature—it’s about people too. Healthy ecosystems support livelihoods, strengthen communities, and offer hope in the face of environmental despair.

The Role of Education and Awareness

Understanding ecosystems is not just for scientists. It is for everyone. The more we understand the interconnectedness of life, the more we are likely to protect it. Education plays a vital role in this process. Children who learn about ecosystems grow up with a sense of wonder and responsibility. Adults who understand ecosystem services are more likely to support conservation.

This awareness can drive policy, inspire activism, and shift consumer behavior. It can turn abstract environmental issues into urgent, personal ones. Because in the end, protecting ecosystems is not about saving nature for its own sake—it’s about preserving the foundation of human life.

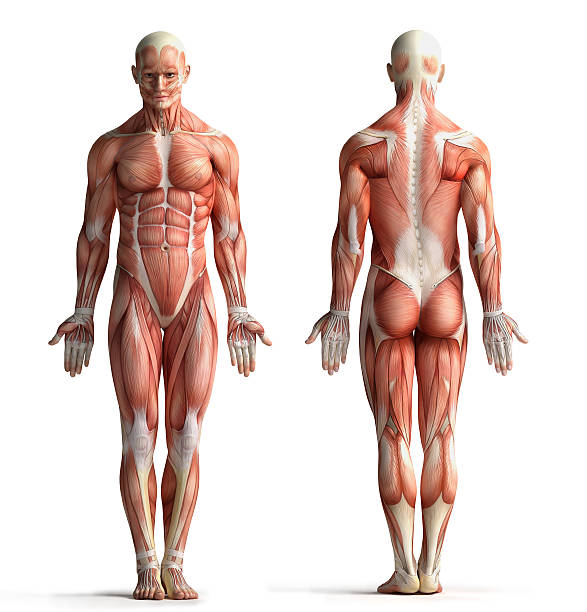

The Ecosystem Within: The Human Body as a Microbiome

To truly grasp the omnipresence of ecosystems, look inward. Your body hosts trillions of microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi—that live in your gut, on your skin, in your mouth. This is your microbiome, a microscopic ecosystem that plays a crucial role in digestion, immunity, and even mental health.

Just like a rainforest or coral reef, your internal ecosystem relies on balance. Disruption—through poor diet, antibiotics, or stress—can lead to disease. Understanding the microbiome reminds us that ecosystems aren’t just “out there.” They are within us. We are, quite literally, walking ecosystems.

Ecosystems and the Future of the Planet

As we look toward the future, the importance of ecosystems becomes ever more urgent. The climate crisis is not just about rising temperatures—it’s about the disruption of ecosystems. The extinction crisis is not just about animals—it’s about the collapse of the systems that support life.

Solutions to our biggest challenges—climate resilience, food security, water availability—are rooted in ecosystem health. Protecting wetlands can buffer against floods. Restoring mangroves can shield coasts from storms. Rewilding landscapes can absorb carbon.

If humanity is to thrive in the coming decades, we must align our societies, economies, and technologies with the rhythms and needs of ecosystems. We must learn not to dominate nature, but to partner with it.