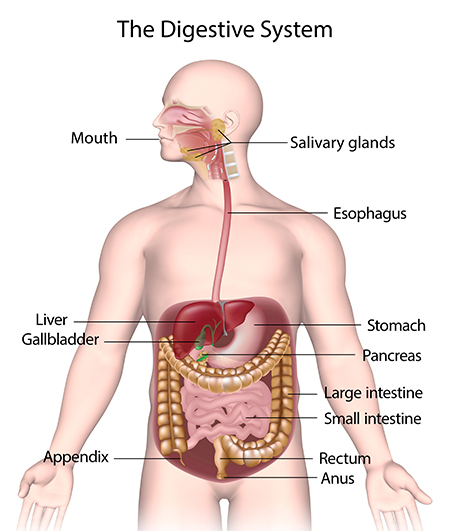

The digestive system is an intricate and remarkable series of organs and processes that transform the food we consume into the energy and nutrients our bodies need to function. While it’s easy to take the digestion process for granted, every bite we take sets off a complex chain reaction that spans multiple organs, systems, and processes. From the moment food enters our mouth to when the waste exits our body, the digestive system works tirelessly to extract essential nutrients, maintain our health, and ensure our survival.

It’s not just a simple act of swallowing and absorbing. The digestive system is a finely tuned machine, with each organ playing a specific role in breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and expelling waste. This system’s efficiency is nothing short of miraculous. But what exactly is the digestive system, and how does it work?

An Overview of the Digestive System

The digestive system includes everything from the mouth to the intestines. At its core, it consists of two main parts: the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and accessory organs like the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. Together, these organs are responsible for a range of tasks: mechanical digestion (physically breaking food down), chemical digestion (enzymatically breaking food down), absorption of nutrients, and the excretion of waste.

The entire process involves a series of steps that take food from the point of entry to the body’s exit. It’s a finely coordinated dance between muscular contractions, digestive enzymes, and specialized cells designed to break down food into molecules small enough to be absorbed and utilized by our cells.

The Mouth: The First Step in Digestion

Digestion begins in the mouth, where food is physically broken down by the teeth in a process known as mastication. This mechanical digestion is the first step in transforming solid food into something that can be easily processed by the stomach and intestines. The teeth chop and grind the food into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for enzymes to work.

But the mouth isn’t just about chewing; saliva plays a crucial role. Produced by salivary glands, saliva contains enzymes like amylase, which begin the breakdown of carbohydrates right in the mouth. This early chemical digestion prepares food for further breakdown in the stomach and intestines.

The tongue also helps move food around the mouth, positioning it for optimal chewing. Once the food is chewed and mixed with saliva, it forms a soft ball called a bolus, which is then swallowed and travels down the esophagus.

The Esophagus: The Passageway

The food bolus now enters the esophagus, a muscular tube that connects the mouth to the stomach. The esophagus’s primary role is to transport food from the mouth to the stomach through a series of wave-like muscle contractions called peristalsis. These rhythmic contractions push the food downward in a controlled manner, preventing it from backing up into the throat.

The process is swift, and within seconds, food is in the stomach, ready for further digestion. But before food enters the stomach, it must pass through the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a valve-like muscle that prevents stomach acid from flowing backward into the esophagus.

The Stomach: Where Food Meets Acid

Once food reaches the stomach, it encounters an environment quite different from the one it left behind. The stomach is a sac-like organ capable of holding about one liter of food at any given time. It has several layers of muscle that contract and churn the food into a semi-liquid substance called chyme.

At the same time, specialized cells lining the stomach secrete powerful digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid. Pepsin, an enzyme activated by the acidic environment, begins the process of breaking down proteins into smaller peptides. The acid also helps kill harmful bacteria and pathogens that may have come along for the ride in the food.

The stomach’s muscular contractions mix the food with these digestive fluids, ensuring it is adequately broken down before it moves into the small intestine. The stomach also acts as a storage area, slowly releasing food into the small intestine in small amounts to ensure that digestion can proceed efficiently.

The Small Intestine: The Powerhouse of Absorption

Next, the partially digested food (chyme) moves into the small intestine, the longest part of the digestive tract, measuring about 20 feet in length. It is here that the majority of digestion and nutrient absorption occurs.

The small intestine is divided into three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. As food enters the duodenum, it is mixed with bile from the liver and digestive enzymes from the pancreas, which help break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates into smaller molecules. Bile is stored in the gallbladder and released into the duodenum when needed. Its primary function is to emulsify fats, breaking them into smaller droplets that enzymes can more easily digest.

The pancreas also plays a critical role by secreting enzymes like lipase (for fats), amylase (for carbohydrates), and proteases (for proteins). These enzymes work to further break down food into its most basic components: amino acids, fatty acids, and simple sugars.

The villi and microvilli, tiny finger-like projections lining the walls of the small intestine, increase the surface area for absorption. These structures are covered in cells that allow nutrients to pass from the digestive tract into the bloodstream. The absorbed nutrients are then transported to various parts of the body where they’re used for energy, growth, and repair.

The Large Intestine: Absorbing Water and Excreting Waste

After the majority of the nutrients have been absorbed, the remaining undigested food and waste products move into the large intestine, also known as the colon. Here, the primary role is to absorb water, electrolytes, and certain vitamins (like vitamin K, which is produced by gut bacteria).

As water is reabsorbed, the remaining material begins to solidify and form stool. The colon is also home to trillions of beneficial bacteria that help break down fiber and other substances that the body cannot digest. These bacteria play a vital role in maintaining a healthy gut microbiome, which is essential for overall health.

Once the waste material reaches the rectum, it is stored until it’s ready to be excreted through the anus. This process is controlled by sphincter muscles that allow for the voluntary release of stool.

The Accessory Organs: Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder

While the digestive tract is responsible for most of the digestion and absorption, several accessory organs work in tandem with the GI tract to facilitate the process.

The Liver: Detoxification and Nutrient Processing

The liver is the body’s largest internal organ and is involved in several key functions, including the production of bile. As food is broken down in the small intestine, the liver processes absorbed nutrients and stores excess nutrients like glucose as glycogen for later use. It also detoxifies harmful substances and helps regulate blood sugar levels.

The liver’s ability to process nutrients is essential for overall health. Without it, the body would struggle to manage the energy it receives from food.

The Gallbladder: Bile Storage and Release

The gallbladder is a small, pear-shaped organ located beneath the liver. It stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver and releases it into the duodenum when needed. Bile plays a crucial role in the digestion of fats by breaking them down into smaller particles that can be absorbed in the small intestine.

The Pancreas: Enzyme Production and Insulin Regulation

The pancreas is another key accessory organ, with dual functions in both digestion and endocrine regulation. It produces digestive enzymes (lipase, amylase, and proteases) that are secreted into the duodenum to assist in food breakdown. It also produces insulin and glucagon, hormones that help regulate blood sugar levels.

The Importance of the Digestive System for Overall Health

The digestive system is not only responsible for the breakdown of food, but it also plays a pivotal role in overall health. When the digestive system is in balance, the body receives all the nutrients, energy, and hydration it needs to function optimally. However, when something goes wrong—whether it’s poor digestion, malabsorption, or a disorder like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or celiac disease—the effects can be far-reaching.

A healthy digestive system supports the immune system, helps detoxify the body, and even influences mood and mental health through the gut-brain axis. The gut microbiome—composed of trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms—also plays an essential role in digestion, immunity, and mental well-being.

Conclusion: A Lifelong Journey of Digestion

The digestive system is one of the most complex and essential systems in the human body. From the moment we take a bite of food to the moment waste exits our body, the digestive system works tirelessly to ensure we get the nutrients we need and rid ourselves of waste. It is a marvel of biological engineering, intricately designed to support our health, energy, and longevity.

Understanding how the digestive system works not only helps us appreciate the complexities of life but also guides us toward making healthier choices. After all, the food we eat, the way we digest it, and the health of our digestive system all play a significant role in how we feel, how we perform, and how we live.