By the time the sun had climbed high over the Guatemalan jungle, the quiet pulse of ancient stone had already begun to speak. Just beyond the heart of Tikal—a towering Maya metropolis known for its majestic pyramids and expansive plazas—a team of archaeologists knelt in the earth. Brushes in hand, they revealed something astonishing: a hidden altar, veiled for over 1,600 years beneath layers of soil, silence, and time.

What they uncovered was more than a stunning artifact. It was a portal—a painted altar so vivid, so distinctly foreign, that it cracked open a mystery scholars have long wrestled with: what happened at Tikal in the late fourth century A.D., during one of the most turbulent chapters in Maya history?

This is the tale of how a carved stone, the bones of a child, and the artistic echo of a distant empire have reshaped our understanding of ancient power, cultural collision, and the human stories caught in the middle.

Tikal: Jewel of the Rainforest, Seed of a Dynasty

Founded around 850 B.C., Tikal began modestly. For centuries, it was a sleepy outpost in the Maya lowlands, its inhabitants farming maize and constructing simple ceremonial sites. But sometime after 100 A.D., it began to blossom. With the birth of a ruling dynasty and the rise of powerful monarchs, Tikal expanded into a city of stone and ambition.

By the time of its golden age, Tikal was a city-state of towering temples, sacred causeways, and sophisticated astronomical knowledge. At its peak, the city may have housed more than 60,000 people, with influence stretching across what is now Guatemala, Belize, and southern Mexico.

Yet even in its glory, Tikal was not isolated. It was part of a vibrant, interconnected world—a world that would one day draw the gaze of a distant, powerful empire to the west: Teotihuacan.

The City of the Gods

Teotihuacan, founded centuries before the rise of Rome, was a marvel of the ancient world. Located outside modern-day Mexico City, it was unlike anything else in Mesoamerica: an urban grid of broad avenues, pyramids as large as Egyptian monuments, and neighborhoods teeming with artisans, priests, warriors, and merchants.

Its name, given centuries later by the Aztecs, means “The Place Where Gods Were Born.” At its height, around 375 A.D., it was the largest city in the Western Hemisphere—home to over 100,000 people.

What made Teotihuacan so enigmatic was its influence. While its rulers left few decipherable inscriptions, its shadow stretches across ancient Mesoamerica. Its obsidian blades, architecture, and deities show up in far-off places. Its warriors, it turns out, may have done the same.

A Painted Altar and a Mysterious Visitor

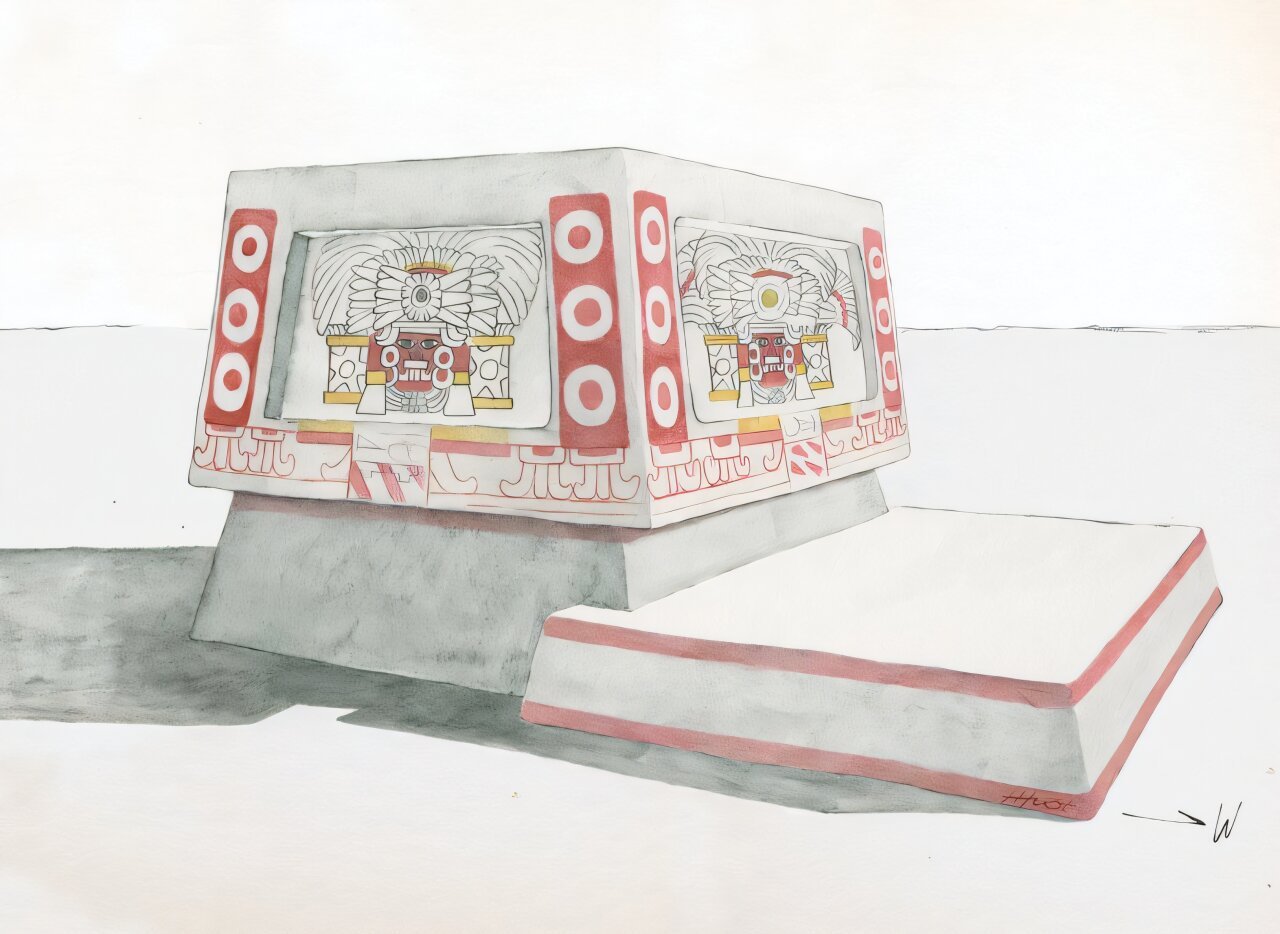

Back in Tikal, archaeologists led by Stephen Houston and Andrew Scherer of Brown University uncovered something that didn’t belong: an altar, dating to the late 300s A.D., carved and painted in vivid reds, blacks, and yellows. The central figure wears a feathered headdress, his almond-shaped eyes peering out beneath heavy lids. He’s flanked by shields, surrounded by sacred symbols.

But this was no Maya ruler.

“The style is unmistakable,” said Houston. “The face, the earspools, the regalia—it’s straight out of Teotihuacan.”

To the trained eye, this altar was not Maya at all, but rather the work of an artist trained in the aesthetics of central Mexico. Somehow, over 600 miles away from the Avenue of the Dead, the visual language of Teotihuacan had appeared in the heart of the Maya world. And it wasn’t alone.

Inside the altar, archaeologists discovered the skeleton of a child, buried in a seated position—a practice common in Teotihuacan but rare in Maya burials. Alongside the child was a green obsidian dart point, a weapon distinct to the central Mexican arsenal. Together, these clues suggested a troubling theory: Tikal wasn’t just trading with Teotihuacan. It was being transformed by it.

From Trade to Takeover

For decades, scholars knew that Teotihuacan and Tikal had contact. Ceramics, obsidian, and cultural motifs flowed between them. But something changed around 378 A.D.—and dramatically.

“It’s almost like Tikal poked the beast,” said Houston, “and got too much attention.”

That attention came in the form of a political takeover. Ancient inscriptions—first discovered in the 1960s—tell of a sudden shift in power. On January 16, 378 A.D., a foreign general known as “Siyaj K’ak’” (“Fire is Born”) arrived in Tikal. That same day, the reigning king died. Within twenty-four hours, a new ruler was installed: Yax Nuun Ahiin I, the son of a foreign king from Teotihuacan.

Whether the original king was assassinated or deposed peacefully is unclear. What is clear is that the old dynasty ended—and the new one bore unmistakable foreign fingerprints.

A Citadel in the Jungle

In 2018, using LiDAR scanning—an airborne laser technology capable of piercing the thick jungle canopy—Houston’s team made another discovery: a sprawling complex near Tikal that was buried under what had long been thought natural hills.

When digitally flattened, the “hills” revealed a stunning truth: they formed a citadel. And not just any citadel, but a scaled-down replica of the central compound in Teotihuacan. Complete with courtyards and symmetrical platforms, this hidden city-within-a-city suggested not only cultural exchange, but direct presence.

“It’s surveillance. It’s a garrison. Maybe even a colony,” said Houston.

The implications were enormous: Teotihuacan may not have just influenced Tikal. It may have occupied it.

Ghosts Beneath the Stone

The newly unearthed altar seems to have been constructed during this very period of upheaval—perhaps as part of the effort to legitimize the new regime or honor the foreign gods. But what makes the site truly eerie is what happened after.

Rather than continuing to use this altar, or build upon it as the Maya often did, they buried it. Not just the altar, but the surrounding buildings too. And then… they left it alone.

To Scherer, this speaks volumes.

“This was prime real estate,” he said. “But they didn’t reuse it. They treated it like a radioactive zone. That suggests deep trauma. A kind of cultural scar.”

It’s a reminder that even in antiquity, memory is powerful. The Maya may have accepted their new rulers, but they did not forget what had been lost—and what it had cost.

Tikal’s Rise from the Ashes

Ironically, Teotihuacan’s intervention may have paved the way for Tikal’s greatest era. In the centuries following the 378 coup, Tikal surged in power. Its rulers—now blending Maya and Teotihuacan heritage—launched military campaigns, expanded trade networks, and constructed some of the city’s most iconic monuments.

By 600 A.D., Tikal stood as one of the most dominant powers in the Maya world. The foreign blood in its royal line had been transformed from liability to legacy.

“There’s almost a nostalgia in the later monuments,” said Houston. “A wistfulness for that moment when they were touched by the great power to the west.”

But nostalgia, as always, is complicated. Beneath the grandeur lay the buried stories: of children offered in sacrifice, of kings overthrown, of cities remade by ambition.

Echoes of Empire

The story of Tikal and Teotihuacan isn’t just about two ancient cities. It’s about the recurring rhythms of history. A powerful empire sees a distant land rich in resources—feathers, jade, chocolate—and moves in, cloaked first in trade, then in might.

It’s a pattern we know well.

“Everyone remembers what happened to the Aztecs when the Spanish arrived,” said Houston. “But our findings show this story is far older. These empires have always reached out to dominate, to remake, to profit.”

And always, the people left behind have had to find ways to remember, to rebuild, and sometimes, to bury.

Conclusion: Stones That Still Speak

More than sixteen centuries after it was sealed, the altar near Tikal still whispers its truths. In its colors, we see art carried across hundreds of miles. In its bones, we find the cost of conquest. In its burial, we sense the mourning of a civilization—grieving, resisting, remembering.

The Maya of Tikal rose again, of course. Their stone cities would gleam for centuries more before time and jungle reclaimed them. But now, thanks to LiDAR, to paintbrushes, and to the persistence of scholars, those stories are resurfacing.

Beneath every stone, a voice. Beneath every altar, a memory. And in the spaces between—our chance to listen.

Reference: Edwin Román Ramírez et al, A Teotihuacan altar at Tikal, Guatemala: central Mexican ritual and elite interaction in the Maya Lowlands, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.3