Have you ever gazed up at pictures of Saturn, its gleaming rings stretching out like cosmic jewelry, and wondered, Why does Saturn get to wear the bling? What about the other planets? Why do some have rings, while others spin in space without so much as a halo of dust? Is it cosmic luck, gravity games, or something else entirely? Sit back, and let’s take an exciting journey through the solar system and beyond, to explore one of the most fascinating mysteries in planetary science.

The Dazzling Dance of the Rings

Let’s start with what we do know. Rings are made up of countless particles, from minuscule dust grains to massive chunks of rock and ice. These particles orbit around a planet in a flat, thin disk. While they might look solid from a distance, like Saturn’s elegant loops, up close they’re more like busy traffic on a multi-lane highway, with each piece moving independently in a carefully choreographed dance.

But here’s where things get curious: four of the gas giants—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—all have rings. Yet Earth? Mars? Mercury? Venus? Not a single ring in sight. Why? What makes ring systems so common for some planets and completely absent for others?

The Short Answer: Gravity, Moons, and Cosmic Collisions

If you want the quick, easy answer, it’s this: rings exist because of a planet’s gravity and its environment. The massive gravitational pull of giant planets like Saturn helps them capture and keep rings in place. Smaller planets just don’t have the muscle for it.

But that’s only scratching the surface. The real story involves ancient moons torn apart by tidal forces, cosmic debris that never became moons, and the delicate balance between formation and destruction in the planet’s gravitational grip.

The Roche Limit—Where Moons Go to Die (or Never Form at All)

The Roche limit sounds like a cool sci-fi concept, but it’s very real. Named after the French astronomer Édouard Roche, this is the invisible boundary around a planet where gravity gets… complicated. If a moon or a large object ventures inside this line, the tidal forces become so extreme that the object can be torn apart by the planet’s gravity. Imagine a world where gravity literally rips things to pieces. That’s the Roche limit in action.

Now picture an ancient moon, perhaps orbiting too close to its planet. Over millions of years, gravitational forces stretch and pull on it until—crack!—the moon shatters into countless fragments. What happens next? Those fragments spread out, forming a glittering ring system that can last for millions or even billions of years.

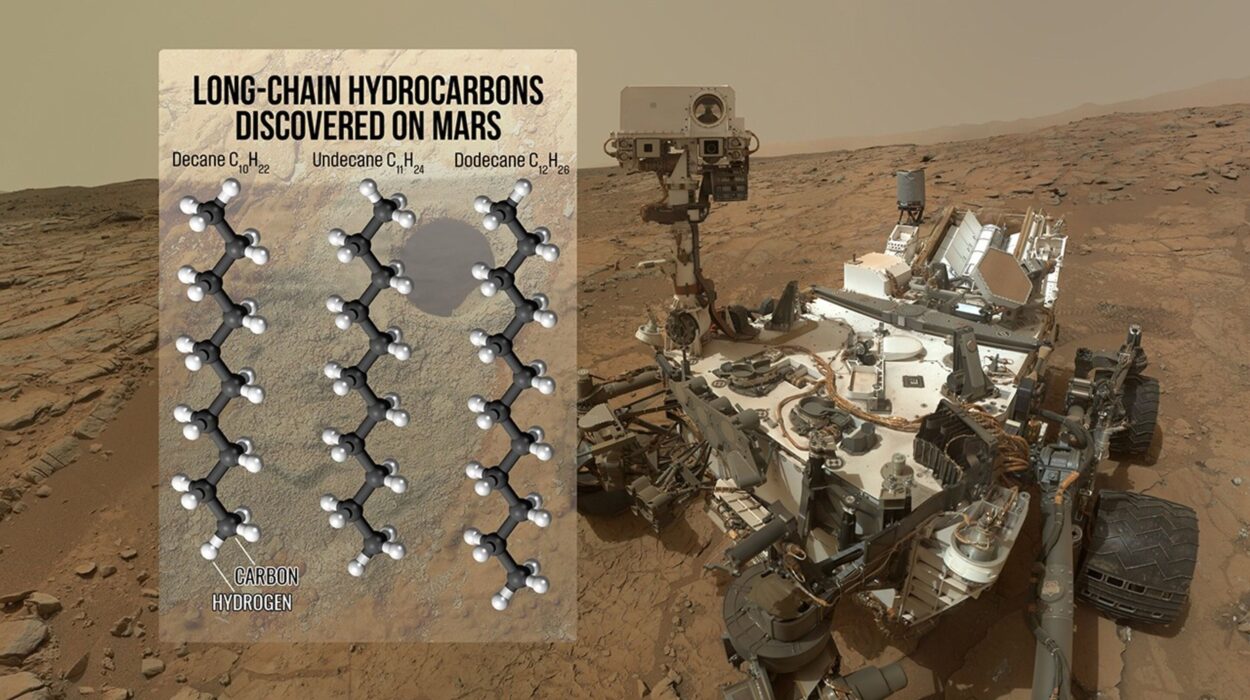

This is one theory for how Saturn’s rings might have formed. Some scientists believe an ancient moon strayed too close and was ripped apart. Others suggest a massive comet or asteroid smashed into a moon, breaking it apart and creating the icy rings we see today.

Big Planets, Big Gravity, Big Rings

Size matters in space. Especially when it comes to holding onto rings. The four giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—are massive. Their gravitational pull is strong enough to keep ring particles in place, preventing them from either crashing into the planet or escaping into space.

Smaller planets, like Earth or Mars, just don’t have the gravitational power to do that. If Earth had a ring system, our gravity would either pull the material down to the surface, where it would burn up in the atmosphere, or the debris would drift away.

But it’s not just about holding onto rings. It’s about how these massive planets got the rings in the first place. Early in the solar system’s history, the giant planets were like cosmic vacuum cleaners, sweeping up enormous amounts of gas, dust, and debris. Some of that debris became moons. Some of it formed rings.

Rings Aren’t Forever (Even Saturn’s Will Disappear Someday)

One of the most mind-blowing facts about planetary rings is that they don’t last forever. Rings are temporary features in the grand timeline of a planet’s life. Even Saturn, the poster child for spectacular rings, is slowly losing them. NASA’s Cassini mission revealed that Saturn’s rings are “raining” onto the planet—tiny particles of ice and dust are being pulled down by gravity and magnetic forces. At the current rate, Saturn’s rings could be gone in about 100 million years. (Don’t worry, that’s still a long time from now!)

So, why don’t rocky planets have rings? One reason might be that they did, once upon a time. But those rings didn’t last. Without a giant planet’s strong gravity and protection from the solar wind, any ancient rings around Mars or Earth could have been pulled down or blown away billions of years ago.

Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune—The Other Ring Bearers

Saturn gets all the fame, but it’s not the only ringed planet. Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune all have rings, too. They’re just harder to see. Saturn’s rings are bright because they’re mostly made of ice, which reflects sunlight brilliantly. The other rings are darker, thinner, and made of dust and rock, which absorb more light and make them practically invisible without powerful telescopes or spacecraft flybys.

Jupiter’s rings, for example, are made mostly of dust kicked up by meteoroids slamming into its small inner moons. They’re faint, thin, and barely there. Uranus has dark, narrow rings made of radiation-darkened particles. Neptune’s rings are incomplete arcs in places, shaped by gravitational interactions with nearby moons.

Moons—The Guardians and Troublemakers of the Rings

Moons play a huge role in the lives of rings. Some moons are responsible for creating rings by shedding material or being broken apart. Others act as shepherds, using their gravity to keep ring particles in neat, narrow lanes.

For example, Saturn’s moon Enceladus constantly spews icy particles into space through geysers at its south pole. Those particles replenish Saturn’s E-ring. Meanwhile, small moons like Prometheus and Pandora act as “shepherds,” keeping Saturn’s F-ring narrow and well-defined.

Moons can also destabilize rings. If a moon’s orbit changes, or it gets too close, it can disrupt ring material, flinging it away or pulling it into the planet. Rings and moons are constantly engaged in a delicate cosmic dance, with gravity as the choreographer.

Why Don’t Earth, Mars, Venus, and Mercury Have Rings?

Now that we know all this, let’s turn our gaze back toward the inner planets—our rocky neighbors. Why no rings?

- Lack of Gravity Muscle: Earth, Mars, Venus, and Mercury are tiny compared to gas giants. Their gravity isn’t strong enough to maintain a stable ring system for long. Any debris close enough to form a ring would likely spiral into the planet or drift away over time.

- The Roche Limit is Closer: Rocky planets have smaller Roche limits. A moon would need to be very close to get ripped apart and form a ring. But being that close often means it was already pulled into the planet or survived intact as a moon.

- Atmospheres and Solar Winds: Inner planets are closer to the Sun, where solar radiation and solar winds are stronger. Any ring particles made of dust or ice would be gradually blown away or pulled into the planet’s atmosphere and burned up.

- Fewer Moons, Fewer Collisions: The inner planets have fewer moons, which means fewer chances for moons to be torn apart or smashed to pieces in collisions. Without those catastrophic events, there’s less raw material to form rings.

Could Earth Get a Ring?

This is where science starts to sound like science fiction—but in the best way. Could Earth one day have a ring system?

In theory, yes. A massive asteroid impact could blast enough debris into orbit to create a temporary ring. Some scientists even believe this might have happened in the past. The giant impact hypothesis suggests a Mars-sized body slammed into early Earth, ejecting material that eventually formed the Moon. Could a similar impact create rings today? Maybe. But the debris would either clump together into a new moon or rain back down to Earth fairly quickly on a cosmic scale.

One wilder idea is artificial rings. Some have proposed that future space projects or asteroid mining operations could lead to debris collecting in orbit around Earth, potentially forming an artificial ring. Of course, the reality of space junk is already a concern, but it’s unlikely we’ll see majestic Saturn-like rings encircling Earth anytime soon.

Ring Systems Beyond Our Solar System

Our solar system’s rings are spectacular, but they’re not unique. Astronomers have discovered evidence of massive ring systems around exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars. One example is the planet J1407b, nicknamed “Super Saturn.” It appears to have a ring system 200 times larger than Saturn’s, stretching tens of millions of kilometers into space.

These giant rings hint at just how varied and dynamic ring systems can be. Studying them helps scientists understand how planets and moons form and evolve—not just here at home, but across the galaxy.

The Cosmic Beauty of Rings—And What They Teach Us

Planetary rings are more than just pretty adornments. They tell stories of destruction and rebirth, of cosmic collisions and gravitational forces at work over billions of years. They remind us of the delicate balance that governs the movements of moons, planets, and stars.

So, why do some planets have rings while others don’t? It’s a combination of mass, gravity, location, history, and sheer cosmic luck. Some planets were in the right place at the right time to capture or create rings. Others missed their chance, or never had the conditions to hold onto them.

But the more we explore, the more we realize: rings are part of the grand, ever-changing story of the universe. And in that story, every planet—whether it wears rings or not—plays a vital role.

Conclusion: Rings Are the Universe’s Way of Showing Off

The next time you look at a picture of Saturn’s rings, or imagine a distant exoplanet with rings large enough to eclipse its star, remember: these structures are temporary, fragile, and absolutely awe-inspiring. They’re evidence of a universe in motion, where gravity sculpts beauty out of chaos.

And maybe—just maybe—one day we’ll find more ringed worlds, or even see Earth wearing rings of its own, however briefly. Until then, we can marvel at the cosmic jewelry that adorns our solar system’s giants, and dream about the unseen wonders waiting out there among the stars.