Quantum computers have long promised to revolutionize industries—from drug discovery to logistics optimization and secure communications. Leveraging the mind-bending principles of quantum mechanics, these futuristic machines process information in a fundamentally different way than classical computers. Unlike the binary bits in conventional systems that toggle between 0 and 1, quantum bits, or qubits, can exist in multiple states simultaneously thanks to quantum superposition. This capability allows quantum computers to tackle computational problems so complex that even today’s most powerful supercomputers are left in the dust.

But while the theoretical potential of quantum computers has captured imaginations across the globe, turning them into practical, large-scale machines is still a monumental engineering challenge. One major roadblock? Connecting the ultra-sensitive, cryogenically-cooled qubits inside quantum processors to external control systems—without compromising their fragile quantum states or turning the system into a miniature inferno.

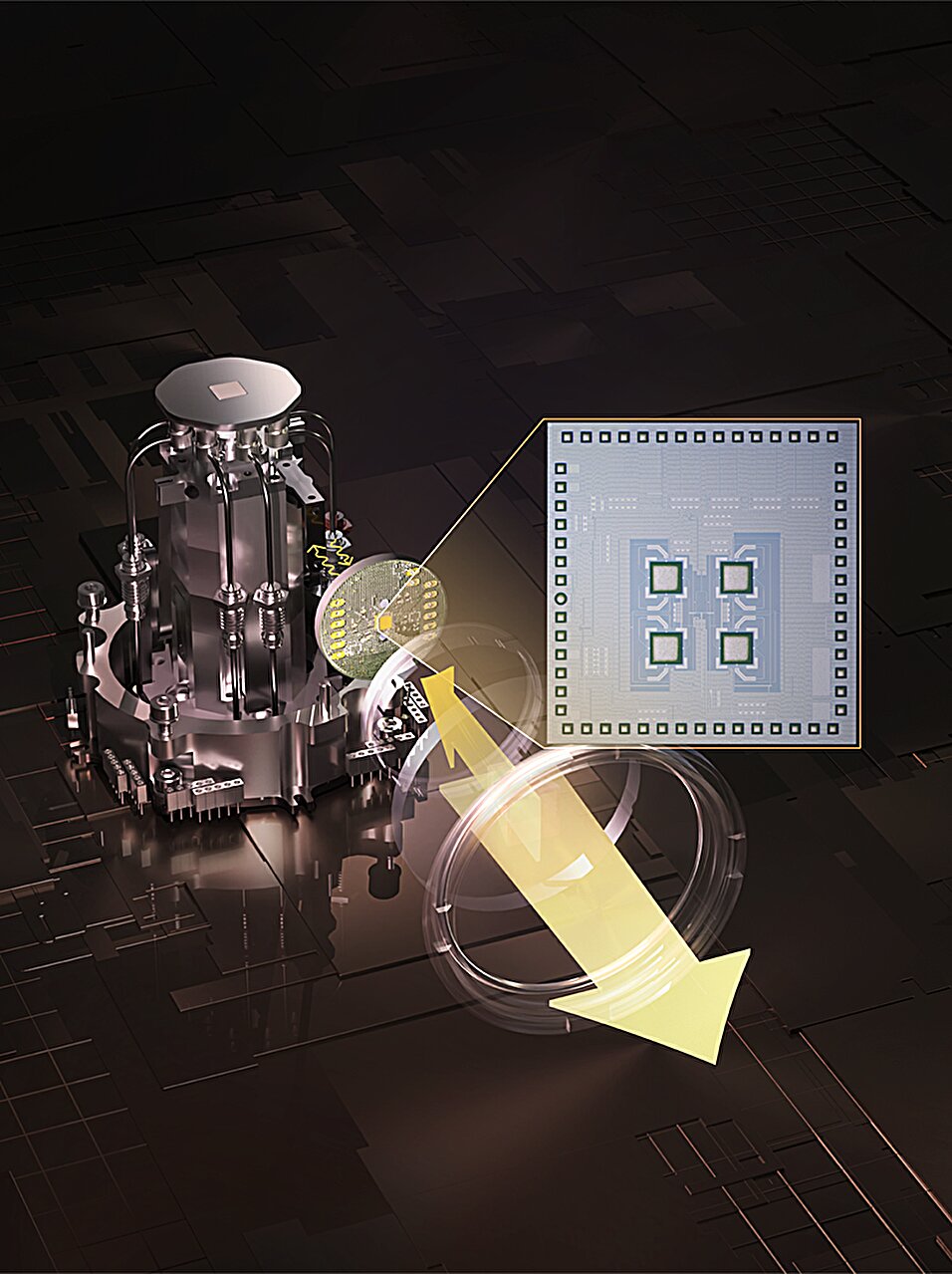

Now, a team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) may have cracked part of the code. They’ve developed a groundbreaking wireless terahertz (THz) cryogenic interconnect, using complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology. This tiny but powerful system promises to usher in a new era of scalable quantum computing—by eliminating the bulky, heat-generating cables that have plagued quantum designs until now.

Let’s break down why this is such a big deal.

The Quantum Bottleneck: Connecting Qubits to the Outside World

Quantum computers are marvels of engineering, but they’re also incredibly delicate. The qubits that power these machines have to be kept at temperatures colder than outer space—just a fraction of a degree above absolute zero. Why? Because heat is the enemy of quantum coherence. Even the smallest disturbance can destroy the qubit’s superposition state, rendering its computational power useless.

The problem arises when you need to control these qubits and read out their results. This requires external electronic systems—controllers that operate at room temperature and send signals back and forth to the frigid core of the quantum processor. Right now, those connections are made using coaxial cables or optical interconnects.

And they work—sort of. The issue is that each of those cables acts like a heat highway, bringing unwanted warmth into the cryogenic environment. For every microwave cable you run from room temperature into the cryo-cooler, you introduce passive heat leakage—around 1 milliwatt per cable.

That doesn’t sound like much until you realize that today’s quantum systems, like Google’s 50-qubit Sycamore, need over 500 of these cables just to function. As quantum systems scale to thousands—or millions—of qubits, the problem quickly becomes insurmountable.

“If the system inside becomes too hot, it cannot remain cool even if millions of watts are expended outside,” explained Jinchen Wang, lead author of the MIT study published in Nature Electronics. This makes scaling today’s designs to a usable, commercially viable quantum computer essentially impossible with existing interconnect solutions.

The MIT Breakthrough: A Wireless Terahertz Lifeline for Qubits

Wang and his colleagues at MIT took a different approach: what if you could cut the cables altogether?

Their answer lies in wireless communication—specifically, in the terahertz frequency range. Operating between 200 and 300 gigahertz, these ultra-high-frequency signals can transmit vast amounts of data with minimal energy loss. But there’s a catch: generating THz signals is notoriously difficult, especially inside the cryogenic environment of a quantum computer.

“Technically, any wireless data transceiver can work,” said Wang. “However, antenna size is inversely proportional to frequency. To ensure the antenna is small enough to be placed in the cryogenic station, we need to increase the wireless frequency to 200–300 GHz.” But the higher the frequency, the harder it is to generate a stable, energy-efficient signal—particularly in the extreme cold.

The MIT team’s solution? Use backscatter communication.

Rather than creating power-hungry THz signals inside the cryogenic zone, the researchers generate them externally—where power isn’t an issue. They then beam these THz carrier waves into the quantum computer’s cryogenic chamber. Once inside, the waves are modulated with control signals or readout data from the quantum processor and reflected back to room-temperature detectors.

Think of it like a mirror reflecting light. The quantum processor doesn’t need to generate energy—it just bounces the signal back with its information embedded. That means no additional heat load inside the delicate cryogenic environment.

The MIT team took it further by incorporating cross-polarization technology, allowing the uplink and downlink signals to share the same antenna by using different polarizations. This minimizes space requirements—crucial in the confined real estate of a quantum computer. They also developed a cold-FET THz detector, a completely passive component with zero power consumption, to detect the returning signals. The result is a streamlined, energy-efficient wireless interface that minimizes both thermal and spatial footprints.

Why This Matters: A Path to Truly Scalable Quantum Computers

In early testing, the wireless THz interconnect performed impressively. It surpassed the energy efficiency of traditional commercial microwave cables with I/O drivers, delivering an astonishing energy efficiency of 34 femtojoules per bit (fJ/bit) on the downlink and 200 fJ/bit on the uplink. To put that in perspective, that’s orders of magnitude more efficient than today’s conventional approaches.

And because the system is based on standard CMOS technology, it’s not only practical but potentially low-cost and highly scalable. Existing semiconductor manufacturing processes could easily adapt to produce these wireless components at scale, accelerating the transition from laboratory prototypes to commercial quantum machines.

But this is just the beginning. Wang and his team are already looking ahead to the next generation of their design. They plan to replace the bulky THz horn antenna with a THz phased array, reducing radiative heat load even further and allowing for multi-channel communication. This means multiple wireless links could operate simultaneously, significantly increasing data bandwidth and enabling even larger quantum processors.

“We anticipate that our efforts will contribute to a real quantum computing system in four to eight years,” Wang said optimistically.

Peering into the Quantum Future

Quantum computers have already achieved remarkable feats, such as Google’s demonstration of “quantum supremacy” in 2019. But these were proof-of-concept systems, not practical, general-purpose quantum computers. The MIT team’s innovation brings us one step closer to that future.

By eliminating the heat bottleneck that’s throttling today’s quantum machines, their wireless terahertz link could finally make large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computers a reality. And with a design based on commercially viable CMOS technology, it’s not just a theoretical solution—it’s one that could be manufactured and deployed in the real world.

If successful, this technology could enable quantum computers to scale from dozens to thousands—or even millions—of qubits, unlocking their full potential for industries ranging from cryptography to pharmaceuticals to artificial intelligence.

And who knows? In the not-so-distant future, the next time someone tells you they “sent a signal into a quantum computer and got an answer back,” it might not be over a bulky cable—it could be riding the invisible waves of a terahertz beam.

Reference: Jinchen Wang et al, A wireless terahertz cryogenic interconnect that minimizes heat-to-information transfer, Nature Electronics (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41928-025-01355-9

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.