The discovery of over 3,000 human bones and bone fragments at Charterhouse Warren, a site dating back to the Early Bronze Age in England, has provided archaeologists with an incredibly rare and chilling glimpse into the violent history of prehistoric Britain. After careful examination, experts concluded that the bones belonged to individuals who were massacred, butchered, and likely partially consumed. This form of violence not only involved the taking of human lives but also served a psychological and cultural purpose: dehumanizing the victims.

While hundreds of human remains from the Early Bronze Age in Britain have been discovered, direct evidence of violent conflict is scarce. The skeletal findings at Charterhouse Warren, however, are distinct. Professor Rick Schulting, the lead author of a study published in Antiquity, explains that the site stands out dramatically in the context of prehistoric violence. “We actually find more evidence for injuries to skeletons dating to the Neolithic period in Britain than the Early Bronze Age,” he states. “So Charterhouse Warren stands out as something very unusual.”

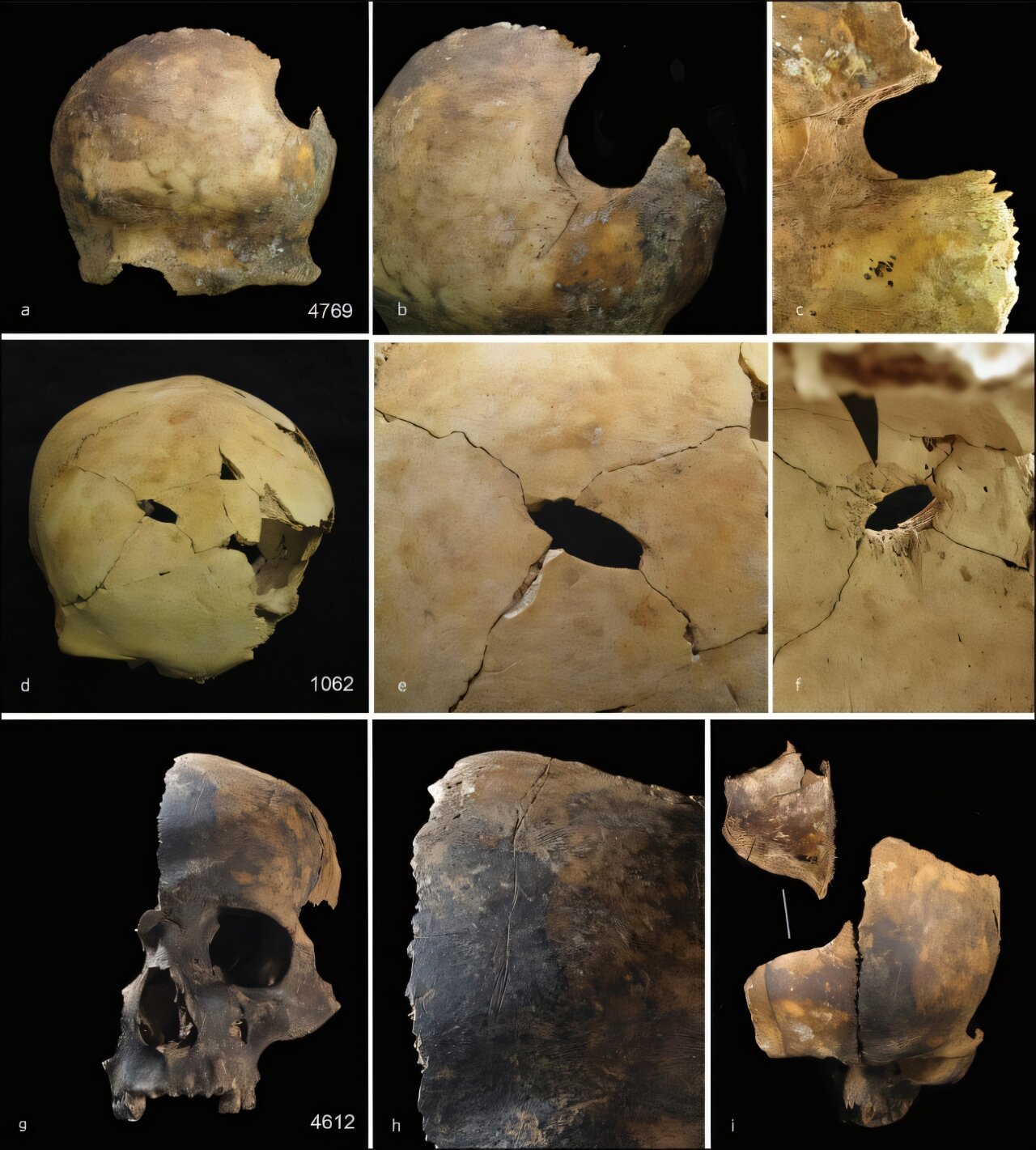

The bones, initially discovered in the 1970s, were scattered within a 15-meter-deep shaft at Charterhouse Warren, located in Somerset. In total, at least 37 individuals—men, women, and children—were identified. These remains were not typical burial relics; instead, they suggested violent death, and the circumstances indicated that they were massacred in a sudden attack. The evidence for blunt force trauma on the skulls indicated that many of the individuals were bludgeoned before being discarded in the shaft.

The archaeological team from several European institutions embarked on an analysis of the remains, examining fractures and cut marks on the bones to gain a clearer understanding of how these individuals met their tragic end. The researchers found a high number of perimortem fractures—breaks occurring around the time of death—on the bones, with many exhibiting cut marks that suggested the bodies were intentionally butchered. The presence of these cut marks on the skulls further raised the question: why would these people have been subjected to such violence, and what led to such brutality?

Unlike previous instances of prehistoric cannibalism, such as the funerary practices seen at the nearby Paleolithic site of Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, where the act was likely ritualistic, the situation at Charterhouse Warren tells a different story. At Charterhouse Warren, there is no evidence of an organized conflict or ritualistic killing, such as a fight that escalated into violence. Instead, the violence was sudden and unprovoked, suggesting that the individuals who were butchered and consumed were massacred unexpectedly by their enemies.

Cannibalism is an incredibly rare and difficult-to-understand practice in the archaeological record, and while it may seem plausible that it was a response to a lack of food, the evidence suggests otherwise. The researchers found that the remains of cattle and other animals were mixed in with the human bones, implying that there was an abundance of food sources available to the people at Charterhouse Warren. Thus, the consumption of human flesh likely had a cultural or symbolic role rather than being born of a necessity for nutrition.

It is likely that cannibalism at Charterhouse Warren served a deeper social function—one that helped further dehumanize the victims. The researchers suggest that by eating the flesh of their fallen enemies and mixing their bones with those of animals, the perpetrators of the massacre were trying to “other” the dead. In a sense, the act of consuming their victims was an attempt to remove their humanity and degrade them to the status of animals. This practice was likely a form of psychological warfare designed to remove any connection between the killers and their victims, to justify their actions, and to reinforce their perceived dominance.

The reasons behind such violence are not entirely clear. Scholars have speculated that social tension, rather than resource competition or ethnic conflict, may have been the primary cause. Evidence suggests that there was no significant impact from resource scarcity or changing climates in Britain during this time. While the idea of ethnic conflict has often been linked with such violence in the ancient world, genetic analysis has shown no evidence of diverse communities living in close proximity, making ethnic or tribal divisions unlikely causes of this conflict.

Instead, social dynamics may have played a central role. Prehistoric societies, especially those from the Early Bronze Age, were likely structured with complex power hierarchies, and personal disputes may have turned deadly. Minor thefts, slights, or insults could have rapidly escalated in the absence of formal legal systems or social protocols. It’s also worth considering the possibility that certain behaviors, perceived insults, or a system of vendetta and revenge could have contributed to an environment in which violence was seen as an acceptable solution to problems.

Moreover, evidence from the study of the bones suggests that disease—specifically, evidence of the plague—may have contributed to the tensions within this society. For instance, scientists discovered traces of the plague in the teeth of two children from the site. While it is still unclear how or whether the disease was connected to the violence at Charterhouse Warren, the presence of such an infectious disease could have heightened fear and mistrust among different groups, exacerbating existing conflicts.

In some ways, this gruesome finding reminds us that acts of extreme violence, including massacres, are not confined to modern times or even more recent historical periods. The violence at Charterhouse Warren serves as an unsettling reminder that societies in prehistory, much like their modern counterparts, could fall prey to cycles of violence rooted in personal disputes, fears, and misunderstandings. The analysis of the Charterhouse Warren site paints a much darker picture of Early Bronze Age Britain than previously imagined and underscores how severe conflict might have occurred even in pre-agricultural and early urban communities.

The study of Charterhouse Warren challenges the conventional narrative of prehistoric Britain as a relatively peaceful society. The idea that the people of the Early Bronze Age could have engaged in massacres and other acts of barbarism—and even practiced cannibalism as part of those acts—adds a dimension to our understanding of the violence that was likely present but less visible in the archaeological record. Charterhouse Warren does not just represent a moment of brutal conflict; it is an insight into the darker aspects of human behavior, where cycles of revenge and retaliation could spiral out of control, leaving behind a legacy of tragedy for the victims and those who would later uncover their remains.

This tragic discovery is an important one for archaeologists and historians, as it deepens our understanding of human prehistory. The fact that it is unlikely to have been a one-off event makes it even more vital to remember its story. For all we understand about early civilizations and prehistory, this unearths a hidden truth: the capacity for cruelty, rooted not just in power struggles but in personal grievances, exists in all cultures throughout time. Understanding the root causes of these conflicts—whether economic, social, or disease-related—allows us to better understand the human condition, not just in the distant past, but also in the context of contemporary global issues.

Reference: ‘The darker angels of our nature’: assemblage of butchered Early Bronze Age human remains from Charterhouse. Antiquity. DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.180

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.