A significant and intriguing discovery made by Dr. Balázs Tihanyi and his team, as detailed in their recent study published in PLOS ONE, sheds light on a fascinating aspect of the 10th-century Carpathian Basin in Hungary. For the first time, the remains of a female burial have been positively identified with weaponry, raising both new questions and opportunities for research regarding the roles of women in ancient warfare and society.

The discovery of female burials containing weapons has long intrigued scholars. For many years, these burials have been viewed with skepticism, leading to debates among archaeologists and historians. Finding weapons within a burial site does not necessarily indicate that the deceased woman was a warrior. Many previous studies have jumped to conclusions about such burials, often without the necessary scientific rigor to fully substantiate the findings. The challenge lies not only in identifying the sex of the individual but also in determining whether weapons in a grave mean the person had any association with warfare or combat.

One of the main complications with interpreting these findings arises from how archaeologists determine biological sex in burial remains. Traditional methods include morphological studies (looking at the physical traits of bones) and genetic analysis. However, these approaches come with their limitations. For example, skeletal remains, particularly in older burials, may be poorly preserved, making morphological analysis difficult. In some cases, contamination of ancient remains with modern human DNA can lead to inaccurate genetic conclusions. As a result, confirming biological sex through these tests can be unreliable. Moreover, just finding a weapon buried with a woman does not immediately classify her as a warrior. Many other factors must be taken into consideration.

The next challenge lies in interpreting whether an individual might have been a warrior. The criteria for warrior status include not only the physical evidence of weapons and trauma but also a deeper understanding of social roles and legal status. Warriors were part of a specific social class that may have had distinct duties, privileges, and ways of living, and these attributes can often remain hidden in the archaeological record. Evidence such as bones displaying certain signs of trauma (from violence or combat) or bone growth changes due to physical exertion (such as repetitive training or horse riding) are important markers, but these might also result from non-warrior activities.

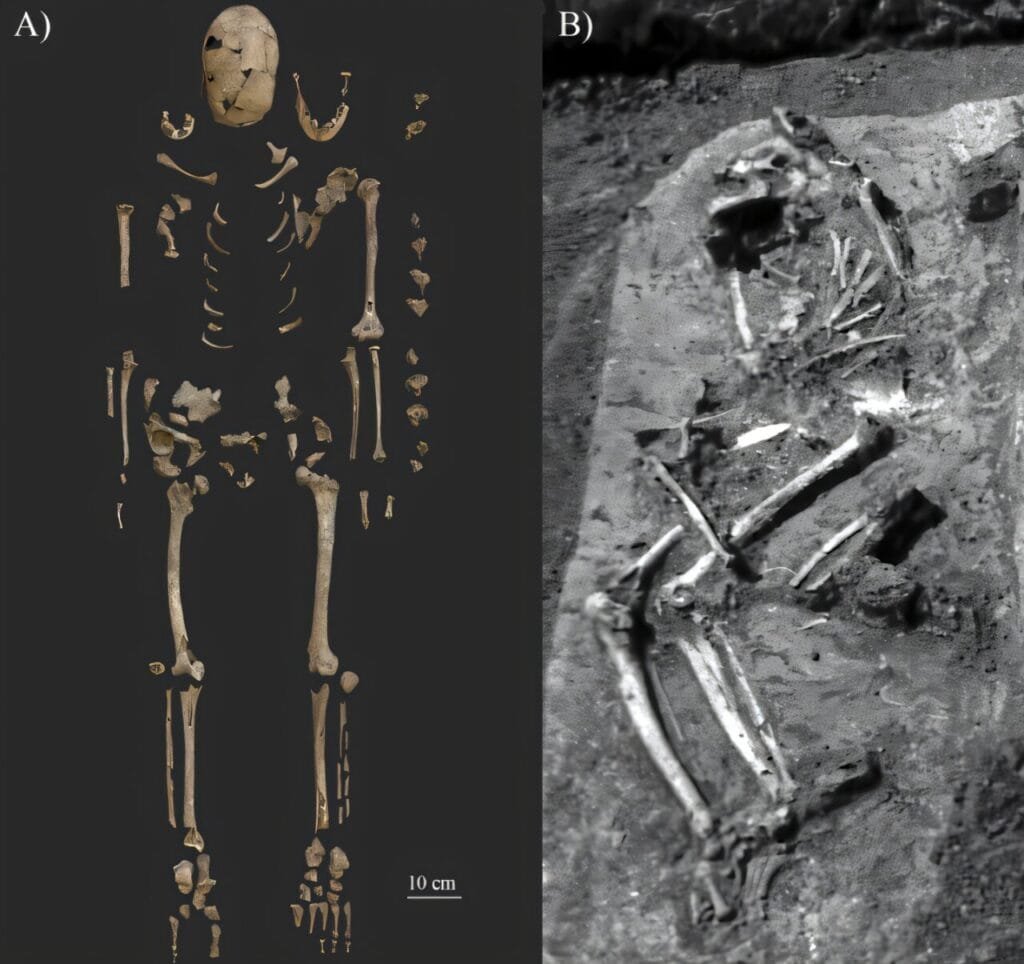

In the case of SH-63, the burial in question, these complexities were at play. The Sárrétudvari–Hízóföld cemetery, where the burial was found, is the largest of its kind from the 10th century CE in Hungary. The site, dating back to the time of the Hungarian Conquest, includes numerous graves with weapons and horse-related artifacts. It is known for hosting the remains of mounted archers, a group that likely played a major role in battles across the Carpathian Basin and Europe. The cemetery contains various burials, but most of them are male, and their grave goods tend to include typical warrior-related items, such as weapons, archery equipment, and sometimes horse-riding tools or horse bones.

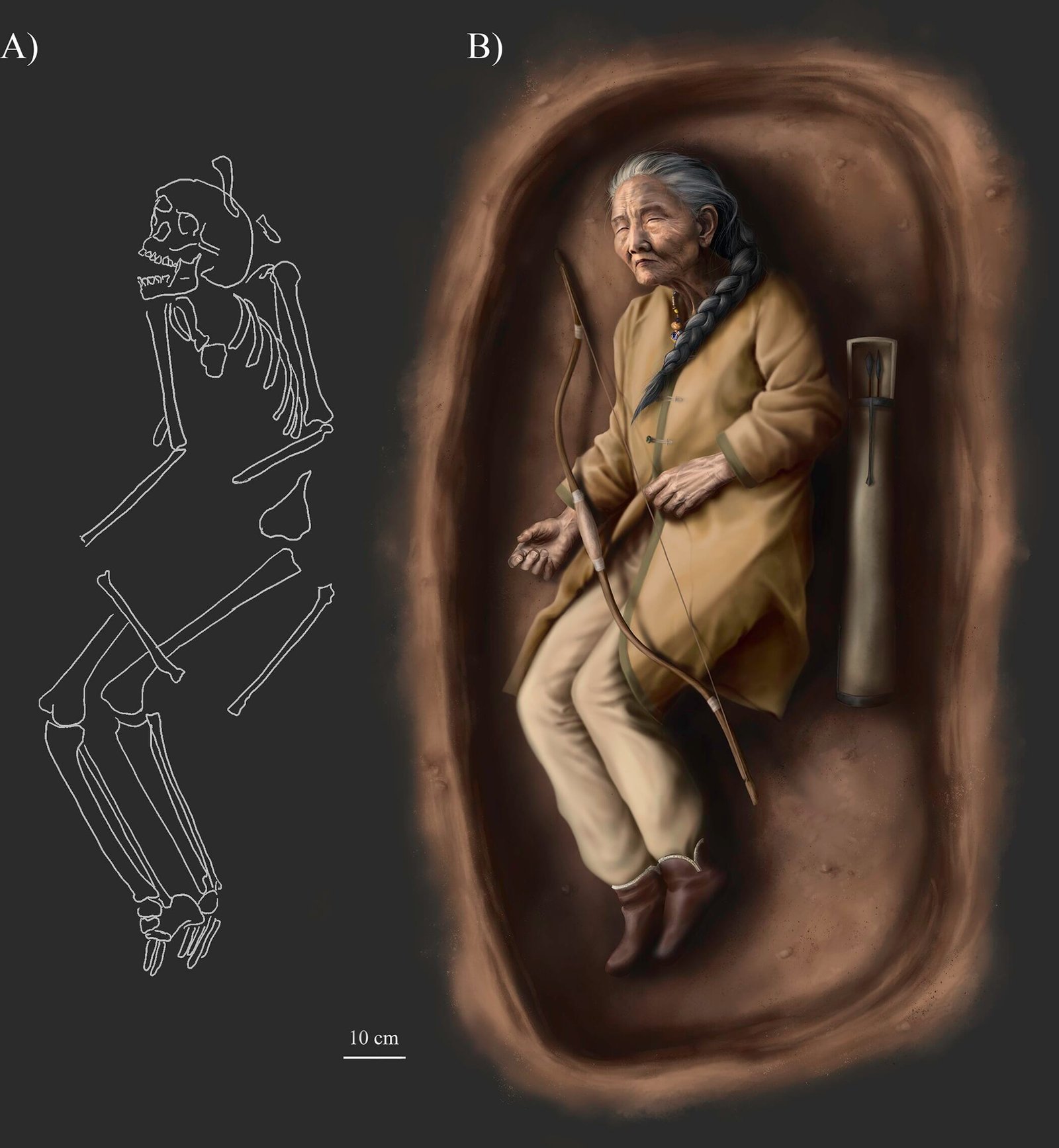

In contrast to the typical male warrior graves, the SH-63 burial contained a combination of items that suggested something unique. While this burial lacked particularly lavish grave goods—common in elite burials—it did feature a mix of characteristics typically associated with women’s graves, including jewelry and clothing fittings, such as a silver penannular hair ring, a string of glass and stone beads, and bell buttons. The real intrigue came from the presence of more martial items: an “armor-piercing” arrowhead, iron parts of a quiver, and an antler bow plate. While the findings were telling, they didn’t conclusively point to SH-63 being a warrior. To make these determinations, the team applied both morphological and genetic analyses.

Genetic testing provided clear support that the individual in question was indeed female, making her the first-known female burial with weaponry in the region. However, additional challenges arose during the morphological assessment of the bones. The preservation of the remains was poor, meaning that critical information regarding age, health, and stature could not be definitively determined. The bones had suffered from significant degradation, making it impossible to evaluate the degree of trauma and whether any activity-related skeletal changes suggested a lifestyle of combat training.

Despite these limitations, the research team was able to discern some crucial health markers, such as signs of osteoporosis, which affects both men and women but is notably more prevalent among older women. This suggests that SH-63 was likely an older individual by the time of death, which in turn suggests that any physical activity would have been more difficult and her bones more fragile in her later years. Trauma-related evidence was also found on her upper limb bones, specifically signs of three major injuries possibly linked to a fall onto the arm or shoulder. These injuries never healed completely, indicating they were sustained at some point in the person’s life and remained with her.

In terms of lifestyle indicators, researchers found significant changes in the joint and ethereal areas of SH-63’s bones. Similar changes had been observed in other graves that also contained weaponry or horse-riding artifacts, indicating that these individuals might have shared similar physical activities. For SH-63, these changes are notable because they suggest she may have participated in strenuous physical activities that resulted in repeated stresses on her body. However, while this may suggest a lifestyle more associated with physical labor, horseback riding, or archery, the evidence was not conclusive enough to definitively label her as a warrior.

Ultimately, the team, led by Dr. Tihanyi, has made an important contribution to our understanding of 10th-century Hungarian burial practices and the role of women in society at the time. While SH-63 may not be definitively categorized as a warrior, her burial is significant in the context of the broader archaeological picture. The presence of weapons in her grave is certainly noteworthy, and further research may help contextualize her social status.

Given the complex and multifaceted nature of burial interpretation, Dr. Tihanyi and his colleagues emphasize that additional comparative studies of other graves from the same cemetery may shed more light on the role women played during the Hungarian Conquest era. These investigations will help illuminate broader cultural patterns and practices. As more evidence emerges, it will be increasingly clear that the everyday lives of 10th-century Hungarians, including women, were far more intricate and varied than previously assumed. SH-63’s unique burial contributes to the growing body of knowledge about social roles, class distinctions, and the physical activities people engaged in at the time.

Moreover, these findings could spark broader discussions about gender and social status in ancient societies, particularly concerning the perceived limitations of women in historical narratives about warriors and fighters. While the traditional image of a warrior has been male-dominated, this study offers a glimpse into the complexity and potential variance of gender roles in ancient warfare and society, suggesting that our understanding of past civilizations is far from complete. As new methods and technologies continue to evolve, we will undoubtedly uncover even more fascinating insights into the hidden stories of those who lived long before us.

Reference: Balázs Tihanyi et al, ‘But no living man am I’: Bioarchaeological evaluation of the first-known female burial with weapon from the 10th-century-CE Carpathian Basin, PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313963