A groundbreaking study led by researchers from the Indiana University School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, and other research institutions has brought to light significant neuroanatomical differences in the brains of children associated with the early initiation of substance use. The study’s findings shed light on the ongoing debate concerning the causal relationship between brain structure variations and substance use behaviors.

Substance use in youth has long been associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders (SUDs) and other adverse outcomes, including academic struggles, mental health issues, and social challenges. Early initiation of substances such as alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and others can pave the way for these complications and profoundly influence brain development. Given that the adolescent brain undergoes significant growth and maturation during this period, substance use can create alterations in brain structure and function. These neuroanatomical changes are considered significant markers of substance exposure, but questions remain about whether the observed brain differences are directly caused by substance use or whether certain neuroanatomical traits predispose individuals to early substance use initiation in the first place.

In their study, titled “Neuroanatomical Variability and Substance Use Initiation in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence,” published in JAMA Network Open, the research team tackled these questions through a longitudinal study design that tracked behavioral development alongside biological growth in children as they progressed from middle childhood into young adulthood. The study aimed to track substance use behaviors while simultaneously examining the changes occurring within their developing brains during this critical period of life.

The study involved 11,875 children aged between 8.9 and 11 years at baseline, who were recruited from 22 research sites across the United States as part of the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which represents one of the largest and most comprehensive studies of adolescent brain development. By using advanced neuroimaging technology, researchers analyzed the brain structure of these participants to look for correlations between early substance use initiation and specific neuroanatomical changes.

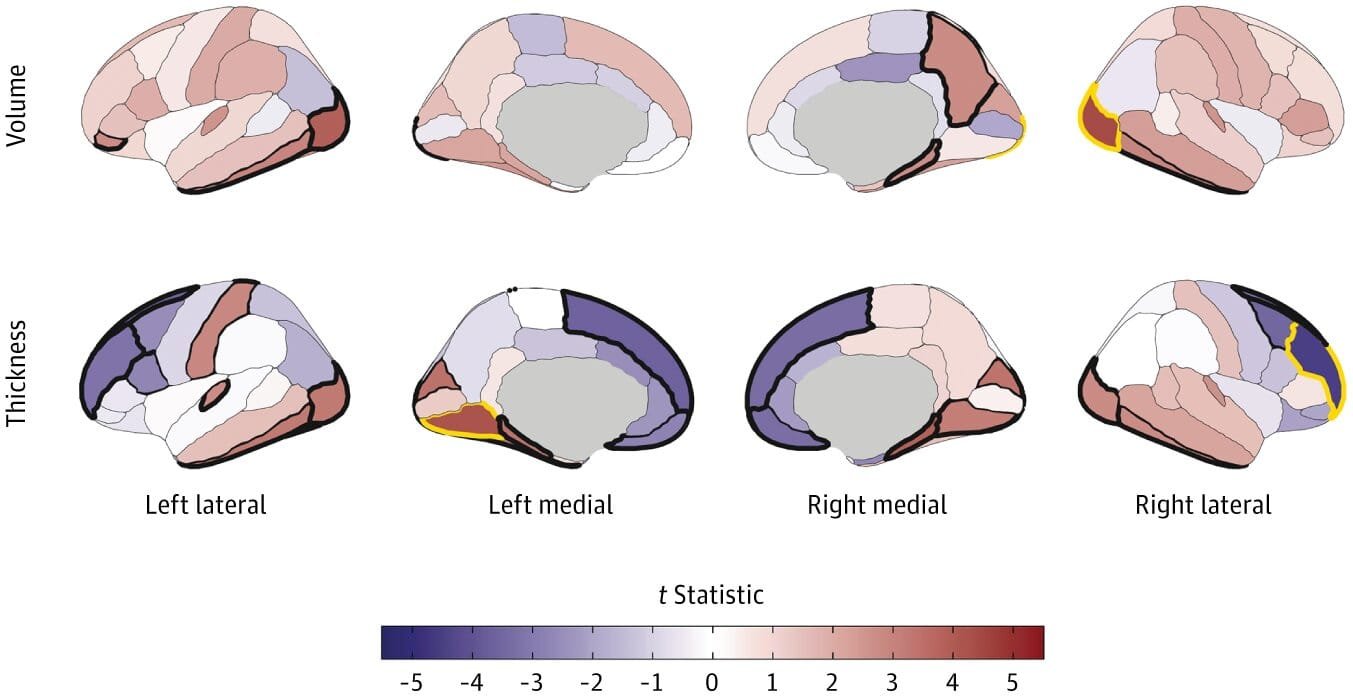

Participants’ substance use habits were tracked, with self-reports detailing the initiation of substances such as alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and other drugs. Each child underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to evaluate their brain structures. Using these images, researchers analyzed 297 distinct brain-related factors, including the overall volume of the brain, cortical and subcortical volumes, thickness of the cortex, surface area, and sulcal depth—all of which help paint a picture of the brain’s anatomy. Numerous factors were considered in the study, including age, sex, pubertal status, family influences, prenatal exposure to substances, and the specific MRI scanners used during the study.

The researchers specifically sought to identify whether preexisting neuroanatomical differences were visible in participants who initiated substance use before the age of 15 and compared these participants with their peers who remained substance-naive until after that age. Post hoc analyses were conducted to exclude children who reported substance use at the baseline in order to focus on the changes in brain structure before any use could have occurred. With a careful approach to statistics and multiple testing corrections, the researchers ensured the reliability of their findings.

What the researchers found was both fascinating and insightful. The study revealed that certain structural brain differences, which were apparent even before the children had started using substances, could be considered potential risk factors for early initiation. These brain differences included larger overall brain volumes, thinner regions of the prefrontal cortex, and greater volumes in specific brain areas, such as the hippocampus and globus pallidus. These differences were particularly noticeable in regions known to be involved in decision-making, impulse control, and reward processing—areas that are directly relevant to the likelihood of making risky decisions like experimenting with drugs or alcohol.

Specifically, the study found significant associations between substance use initiation and cortical thinning in the prefrontal cortex, particularly in the rostral middle frontal gyrus. Interestingly, regions associated with sensory processing, including areas in the occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes, displayed an increase in cortical thickness among children who later went on to use substances. Larger volumes were noted in the hippocampus and globus pallidus in children who would eventually engage in substance use, although cannabis use was particularly linked to reduced right caudate volume.

These neuroanatomical findings were notable in children who had yet to initiate substance use, suggesting that the structural brain differences they exhibited might not be a direct consequence of using substances. Instead, these changes appeared to reflect a preexisting condition, highlighting neuroanatomical variation as potentially inherent traits that predispose some children to experiment with drugs or alcohol earlier than others.

In total, 3,460 participants (about 35.3% of the sample) reported initiating substance use before the age of 15. Among this group, alcohol was by far the most commonly used substance, with nearly 90% of those who began using substances early reporting alcohol as their first choice.

One of the most interesting insights from the study, which was bolstered by further analyses of children who had never used substances at baseline, is that these brain differences were not merely a consequence of the substances but could have preceded and potentially even contributed to the initiation of substance use. This challenges earlier assumptions about the directionality of the relationship between brain changes and early drug use—do the drugs change the brain, or do pre-existing brain differences make certain individuals more prone to using substances?

To complement the study, an invited commentary by experts Felix Pichardo and Sylia Wilson from the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota provided further insight into the study’s broader implications. They underscored the value of the large sample size and longitudinal nature of the ABCD Study, which included genetically informative components. Such detailed and diverse data sources allowed for stronger causal inferences, which could challenge the traditional models of addiction and brain diseases. Their commentary highlighted that this kind of research opens the door to rethinking our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying addiction and how addiction should be conceptualized as part of a broader health and developmental issue.

The implications of this study are far-reaching, especially in terms of how scientists think about addiction risk and the identification of at-risk populations. Early substance use intervention strategies could be improved by considering the neuroanatomical predispositions of certain individuals. It also offers compelling evidence for preventive measures targeting youth, particularly those with brain differences in areas connected to risk-taking behavior.

The results of this study also align with those from other recent studies in the field of adolescent brain development. In one study mentioned by the researchers, psychotic symptoms were found to precede cannabis use, echoing the idea that certain mental health conditions may overlap with or even contribute to risky substance use behaviors.

Ultimately, this research highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted factors that influence adolescent development, including biological, environmental, and social components. As scientists continue to investigate the neural underpinnings of behavior, they may uncover pathways that allow for earlier intervention, reduced risk, and more personalized approaches to supporting healthy adolescent development.

References: Alex P. Miller et al, Neuroanatomical Variability and Substance Use Initiation in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence, JAMA Network Open (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.52027

Felix Pichardo et al, The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study and How We Think About Addiction, JAMA Network Open (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.51997