In an exciting new study, a biological anthropologist at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, John Charles Willman, has proposed a fascinating theory to explain the mysterious flat patches found on the sides of teeth in ancient Europeans. These unusual dental markings, found in remains from the Paleolithic era, have long baffled archaeologists. However, Willman’s hypothesis, published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, suggests that the flat patches may have been caused by the use of labrets—a type of facial piercing—and offers new insight into the practices of ancient humans.

What are Labrets?

Labrets are a form of facial piercing that have been practiced by various cultures for thousands of years. The procedure involves creating a hole in the cheek, near the mouth, and then inserting an object into the hole. In modern times, labrets are typically made of materials like stainless steel or plastic. However, in the distant past, particularly during the Paleolithic era, they would likely have been made of organic materials such as wood, bone, leather, or stone—materials that, due to their natural composition, could easily decay over time, making direct evidence hard to come by.

Although many modern cultures use labrets for aesthetic or social reasons, their practice in ancient times was not widely understood. The existence of flat patches on ancient teeth, especially in the Pavlovian people—who lived in Central Europe between 25,000 and 29,000 years ago—has perplexed researchers for years. Willman’s study aims to solve this riddle by proposing that the wear patterns on these teeth were the result of labrets being inserted into the mouths of these ancient humans.

The Discovery of Flat Patches on Teeth

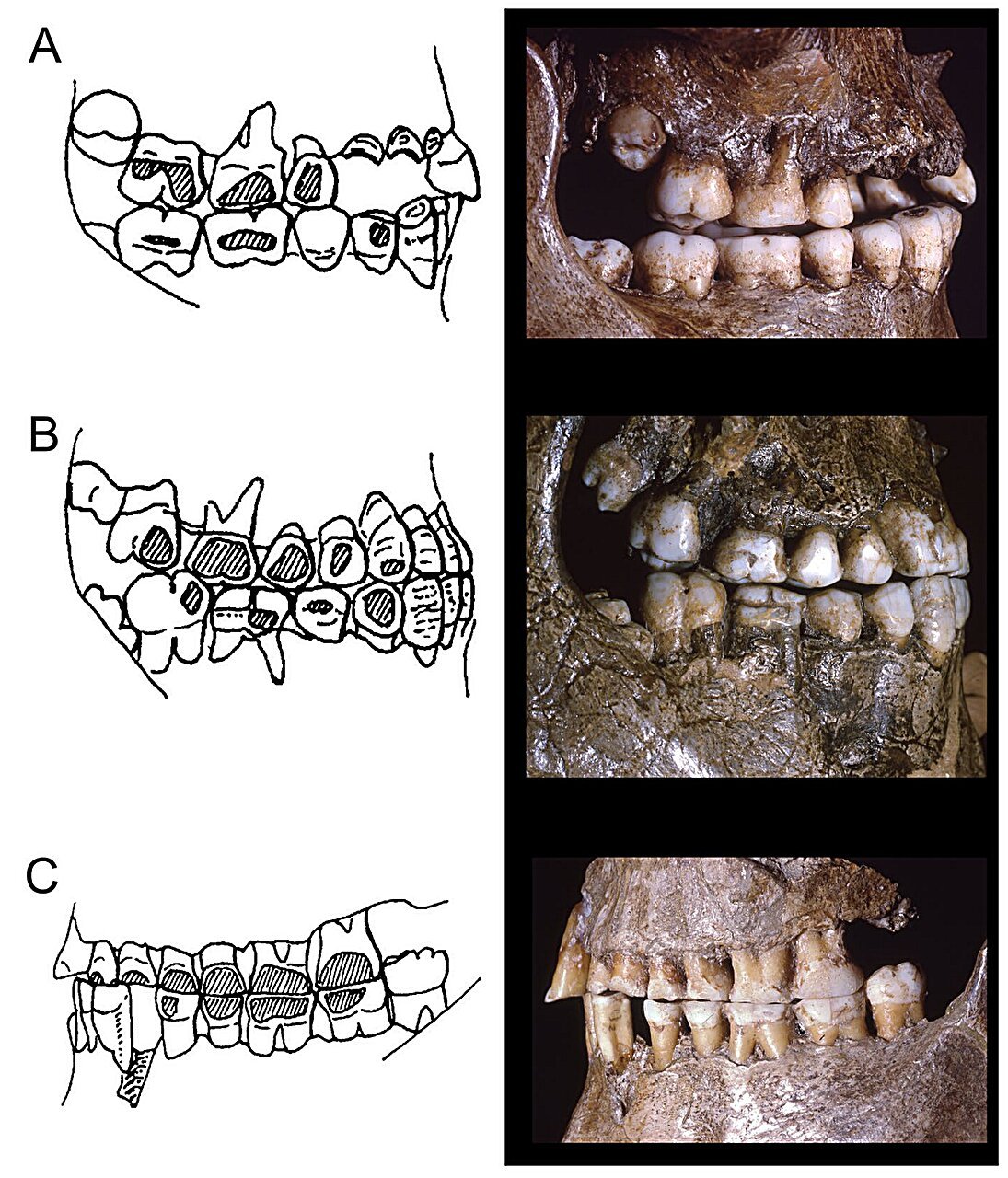

The discovery of flat patches on the teeth of ancient Europeans, particularly among the Pavlovian people, has been a longstanding mystery in archaeology. These flat, polished areas appear on the outer sides of teeth, typically on the molars and premolars, and are most noticeable on the sides facing the cheek rather than the tops or chewing surfaces. This was a significant clue for Willman, as it raised an important question: why would wear occur on the sides of the teeth, rather than in the more typical areas associated with chewing or grinding food?

Previous research had shown that certain behaviors—such as tooth grinding, or the use of objects like pipe stems, could result in flat spots on teeth. These behaviors, though, tended to create wear on the tops of the teeth. The flat patches on the Pavlovian teeth, however, were located on the sides, a feature that couldn’t be easily explained by simple eating habits or tooth-grinding alone.

The Role of Labrets in Ancient Cultures

To explain this unique pattern of wear, Willman turned his attention to the labret practice. Labrets have a long history of use in various parts of the world, including among many indigenous groups in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Historical records suggest that humans have been using labrets for body modification, social signaling, and cultural identity for thousands of years. Willman points out that the cultural use of labrets dates back to the Paleolithic period, and evidence from other ancient human cultures suggests that such practices were not uncommon.

The primary idea behind Willman’s theory is that the constant contact between the labret and the side of the teeth over time caused wear on the enamel, producing the flat patches found in the remains of the Pavlovian people. When the labret was inserted into the cheek, it would likely have rubbed against the teeth, especially during speech, eating, or even gesturing. This repetitive action would naturally result in the abrasion of the teeth’s outer surfaces.

Evidence and Supporting Data

In his paper, Willman focused on Pavlovian skulls that had been unearthed over many years, with intact teeth providing him a unique opportunity to study the wear patterns. He analyzed dozens of skulls, closely examining the teeth for signs of wear. Through this analysis, Willman observed that the flat spots were remarkably consistent across multiple individuals, providing solid evidence that this was a common trait among the Pavlovian people.

Moreover, Willman pointed out a particularly telling detail: the flat patches appeared on the teeth of children as young as ten years old. This suggested that the use of labrets may have been introduced at a young age, perhaps as part of a rite of passage or cultural practice that denoted an individual’s inclusion into a group or age bracket. It’s possible that children were given labrets as a sign of growing maturity, with the flat patches growing larger over time as the individual aged and moved into different social roles.

This idea is supported by the fact that the flat patches seemed to increase in size as the person grew older, suggesting that the wear caused by the labret continued to intensify with age, marking progression through various stages of life and perhaps indicating a deeper cultural significance attached to the practice.

A Possible Social and Ritualistic Function

Willman suggests that labrets could have served not only as a form of individual identity but also as a marker of social status or rites of passage. In many ancient societies, body modifications like piercings or tattoos were used to denote important social milestones, such as puberty, marriage, or leadership roles. The fact that flat patches appeared in children’s teeth might indicate that the placement of labrets was a form of social inclusion, a practice reserved for certain age groups or individuals who had achieved specific milestones within their community.

This hypothesis also leads Willman to propose that archaeologists should start looking for more direct evidence of labrets in future archaeological digs. While the direct physical evidence of ancient labrets is rare, the dental wear caused by these objects could be a more readily identifiable marker, suggesting that the practice was widespread in ancient European cultures.

The Challenge of Confirming the Hypothesis

Although Willman’s hypothesis is compelling, confirming it remains a challenge. The materials used to make labrets in the Paleolithic, such as wood, bone, or leather, would have likely decomposed over time, leaving no physical trace behind. Moreover, labrets would have been worn inside the cheek, which makes them more difficult to identify in the archaeological record compared to more visible body modifications, such as tattoos or facial piercings.

To verify his theory, Willman suggests that further excavations and studies of Paleolithic remains could provide more evidence of the practice. He advocates for closer examination of teeth from other archaeological sites, especially those in areas where labret use has been documented in later historical periods. If labrets were indeed a widespread cultural practice, there may be other signs, such as wear patterns or possible remnants of the materials used for the piercings, that could help corroborate his hypothesis.

Implications for Understanding Ancient Cultures

If Willman’s theory is proven correct, it would provide significant insight into the social structure and cultural practices of ancient European communities. It would suggest that these people engaged in intricate, ritualistic practices of body modification, and that the labret had a role in marking important life stages, social affiliation, and possibly even identity. The idea that young people might have received their labrets as a rite of passage or a sign of belonging is a fascinating cultural insight into their world.

More broadly, Willman’s research highlights the importance of studying tooth wear and dental modifications in archaeological anthropology. The examination of ancient teeth, once thought to be merely a record of diet and oral health, is now revealing itself as a window into the personal and social lives of prehistoric humans.

Conclusion

John Charles Willman’s hypothesis regarding the labret-induced dental wear in the Pavlovian people opens up new avenues for understanding the cultural practices of ancient Europeans. His suggestion that the flat patches on teeth were caused by the placement of labrets challenges traditional views of ancient body modification and offers new insights into the ritualistic and social functions of facial piercings. Although further research and excavation will be required to confirm this theory, Willman’s work invites a reexamination of the role that body modification played in the social dynamics and rituals of our prehistoric ancestors. The study of ancient dental wear is proving to be a rich and revealing field, one that promises to deepen our understanding of the lives of those who came long before us.

Reference: John Charles Willman, Probable Use of Labrets Among the Mid Upper Paleolithic Pavlovian Peoples of Central Europe, Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s41982-024-00204-z