An exciting new discovery by an international team of researchers offers fascinating insights into the early development of Ecdysozoa, a diverse and significant group of animals that includes roundworms, velvet worms, insects, and crustaceans. The discovery consists of fossilized embryos dating back approximately 535 million years, making them some of the oldest and best-preserved embryonic specimens of this group. These fossils were uncovered in the early Cambrian Kuanchuanpu biota of southern Shaanxi Province, China, a region renowned for its rich fossil record.

The research, which was led by Professor Zhang Huaqiao from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, was published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. This groundbreaking study adds significant detail to our understanding of the evolutionary developmental biology of Ecdysozoa, a lineage that includes some of the most ecologically and economically important organisms on Earth. While fossils of invertebrate embryos are rare, when they are preserved, they provide invaluable clues about the development of extinct species and the early evolutionary stages of major animal groups.

Fossilized embryos of early animals are exceptionally rare, and most of the specimens found so far belong to cnidarians or Markuelia, a taxon of scalidophoran. These groups, though vital to the history of life on Earth, do not provide the same depth of understanding about Ecdysozoa, which have become dominant members of the animal kingdom. The Kuanchuanpu biota, an exceptional site for understanding early Cambrian life, is known for its abundant and diverse cnidarian embryos and their developmental stages, but until now, fossilized embryos of Ecdysozoa had not been identified in this area. This gap in the fossil record has now been filled by the discovery of seven well-preserved embryos that exhibit characteristics that are distinctively ecdysozoan.

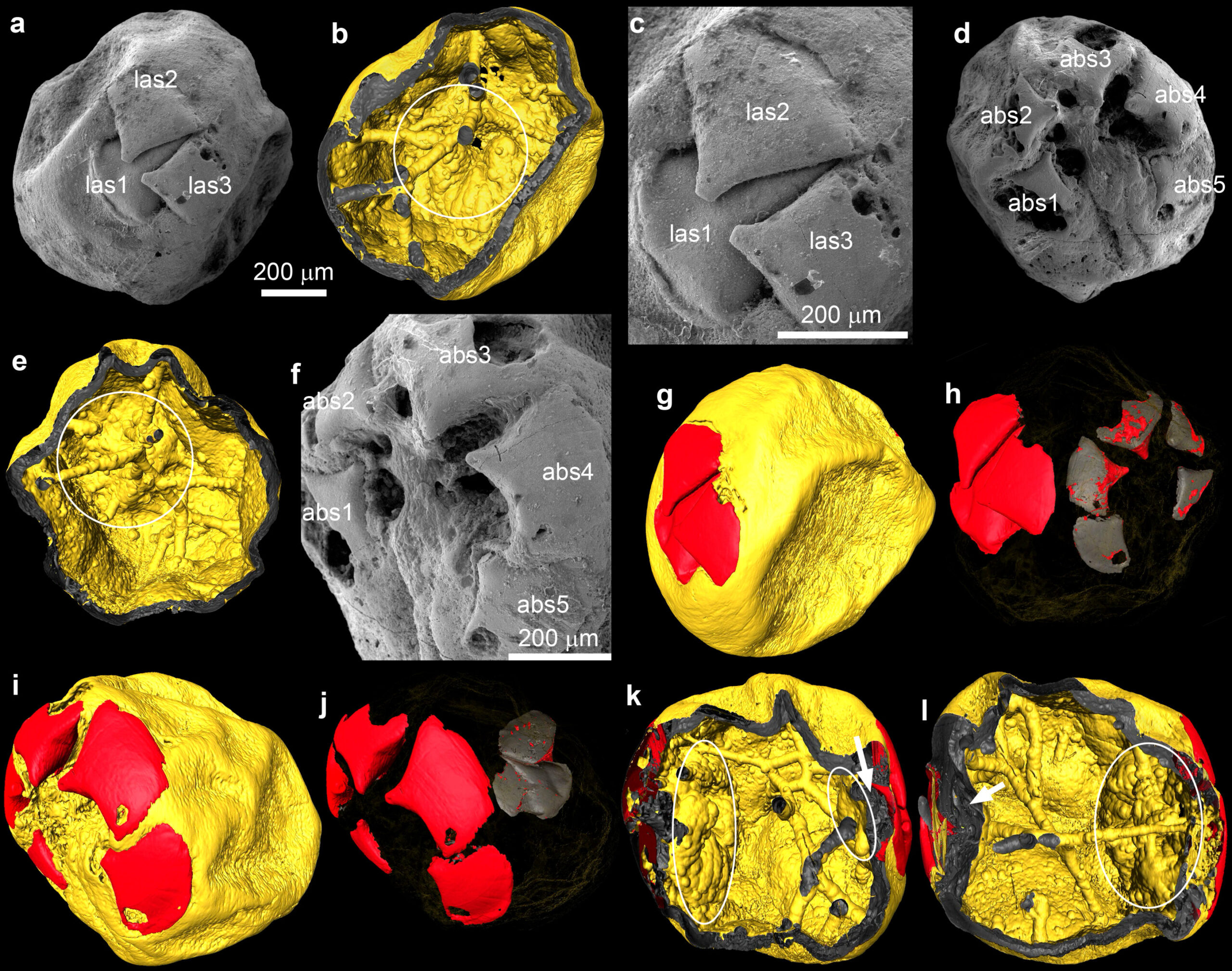

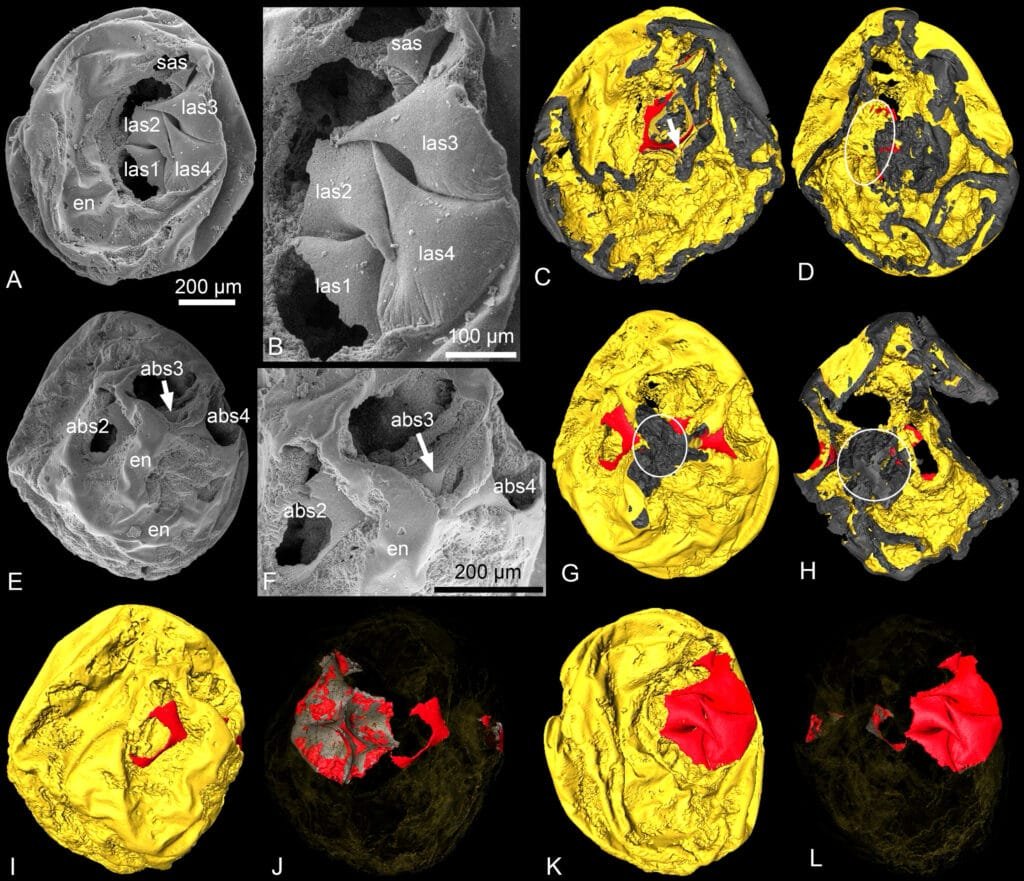

The embryos were found in the early Fortunian stage of the early Cambrian, within the Kuanchuanpu Formation, specifically in the Zhangjiagou section in Xixiang County, Hanzhong City, Shaanxi Province. These embryos were preserved as three-dimensional phosphatized specimens, which is an exceptional form of preservation that allows for detailed study of their morphology. The study employed advanced imaging techniques, including micro-CT scanning, to explore the embryos’ internal structures. The results revealed that the embryos were hollow, with no preserved soft internal anatomy, a feature that is not uncommon in fossilized specimens due to the fragile nature of soft tissues.

Despite the lack of internal preservation, the embryos exhibited several distinguishing features that were crucial for classification. Based on the arrangement and number of sclerites (hard, often cuticularized body parts) at the anterior and posterior ends, the researchers identified the embryos as belonging to two new taxa: Saccus xixiangensis and Saccus necopinus. These new taxa add to the growing body of knowledge about the early stages of Ecdysozoan evolution, revealing important clues about their development and potential evolutionary relationships.

The embryos themselves are characterized by a thin, smooth outer envelope, with diameters ranging from 730 μm to 1 mm, indicating that they were relatively large for embryos of this age. The size of the embryos suggests they were yolk-rich, which implies a lecithotrophic mode of development. Lecithotrophic embryos rely on yolk as an energy source, meaning they do not need to feed externally until they hatch or reach later developmental stages. This is a significant finding, as it suggests that these early Ecdysozoans, like modern-day members of this group, likely developed through a similar energy-efficient strategy, enabling them to survive in the challenging conditions of early Cambrian environments.

The embryos display a bag-shaped body, devoid of introverted or paired limbs, and their integument (outer covering) is non-ciliated, which is an important distinguishing feature for classifying them as Ecdysozoans. The anterior sclerites are arranged in a radial pattern, while the posterior sclerites exhibit bilateral symmetry, indicating that the embryos belonged to bilaterally symmetrical organisms. This is a critical observation, as bilateral symmetry is one of the defining characteristics of Bilateria, the group that includes most animals, including humans. These embryos, therefore, represent early bilaterians, and their study helps bridge the gap between simple, radially symmetrical animals and more complex bilaterians that evolved later in the Cambrian.

One of the most intriguing aspects of these embryos is the presence of cuticularized sclerites. These structures are thought to be hardened body parts that provide protection and structural support to the developing embryo. The cuticularization of these sclerites is a hallmark of Ecdysozoa, a group that is defined by the presence of an external cuticle, which is shed during growth through a process called ecdysis or molting. This finding strengthens the hypothesis that these embryos belong to the Ecdysozoa, a group that includes arthropods, nematodes, and several other phyla.

Despite the wealth of information provided by these embryos, several aspects of their development remain unclear. For instance, the exact mode of development of the Saccus embryos is still uncertain. While the embryos were found in a late-stage developmental state, it is unclear whether they hatched as lecithotrophic larvae that would undergo metamorphosis into their adult forms, or if they underwent direct development, emerging as juvenile forms that resembled miniature adults. The lack of hatched specimens leaves open the possibility that the embryos underwent indirect development, in which they would hatch and develop through a series of larval stages before transforming into their adult form. Alternatively, direct development would imply that the embryos hatched as juveniles that were already capable of feeding and growing into adults without a distinct larval stage.

Regardless of the developmental strategy, these embryos likely represent an important phase in the evolution of body shapes within Ecdysozoa. The bag-shaped body of the Saccus embryos is similar to that of other early Cambrian fossils, such as Saccorhytus, which also exhibited a bag-like body plan. If Saccus and Saccorhytus belong to the stem group of Ecdysozoa, it suggests that this body plan may have been a primitive trait for early Ecdysozoans, while more complex body shapes, such as the vermiform (worm-like) bodies seen in modern Ecdysozoans, evolved later.

The discovery of these fossil embryos provides an exciting glimpse into the early developmental stages of Ecdysozoa and offers critical insights into their evolutionary history. By identifying and studying these well-preserved specimens, researchers have gained new perspectives on the early diversity of life and the complex developmental processes that laid the foundation for modern animal groups. The finding also underscores the importance of the early Cambrian period as a time of rapid evolutionary experimentation, when many of the major body plans and developmental strategies seen in modern animals first emerged. As further research is conducted on these fossils, it is likely that even more detailed information will emerge, helping to refine our understanding of the origins of Ecdysozoa and the evolutionary pathways that led to the vast diversity of life we see today.

Reference: Mingjin Liu et al, New ecdysozoan fossil embryos from the basal Cambrian of China, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112635

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.