Iceland has a deep-rooted and fascinating literary tradition, which has endured and evolved over centuries. Despite its small population of around 380,000, the nation has produced a remarkable array of writers and storytellers, often inspiring the observation that nearly every Icelander has at some point written a book. This legacy of literary excellence stretches back to the Middle Ages, intertwining oral traditions, unique historical circumstances, and cultural exchanges with the rest of Europe.

An often-cited theory is that Iceland’s isolated geography, coupled with its stark and challenging landscape, fostered a culture where storytelling became a vital source of entertainment and intellectual engagement. However, historical evidence challenges the simplistic notion of isolation. Icelanders were deeply interconnected with European culture during the medieval period, maintaining strong contacts with Britain, Germany, Denmark, and Norway. The vibrant intellectual exchanges of the time enriched Iceland’s cultural fabric, solidifying its role as a knowledge society long before modern conceptions of global connectivity emerged.

One of the most significant contributions of Icelandic literary tradition lies in the documentation of royal history. Icelanders have played a pivotal role in preserving knowledge about Norway’s early Viking-age rulers, including their lineage up to the death of King Magnus V Erlingsson in 1184. Skilled poets known as “skalds” often served Norwegian kings, composing intricate verses that celebrated their patrons’ deeds and preserved their legacies in collective memory. Eventually, these oral narratives were meticulously transcribed into written texts, many in Old Norse and Latin. Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson, for instance, became one of the foremost figures in compiling these royal sagas in the 13th century.

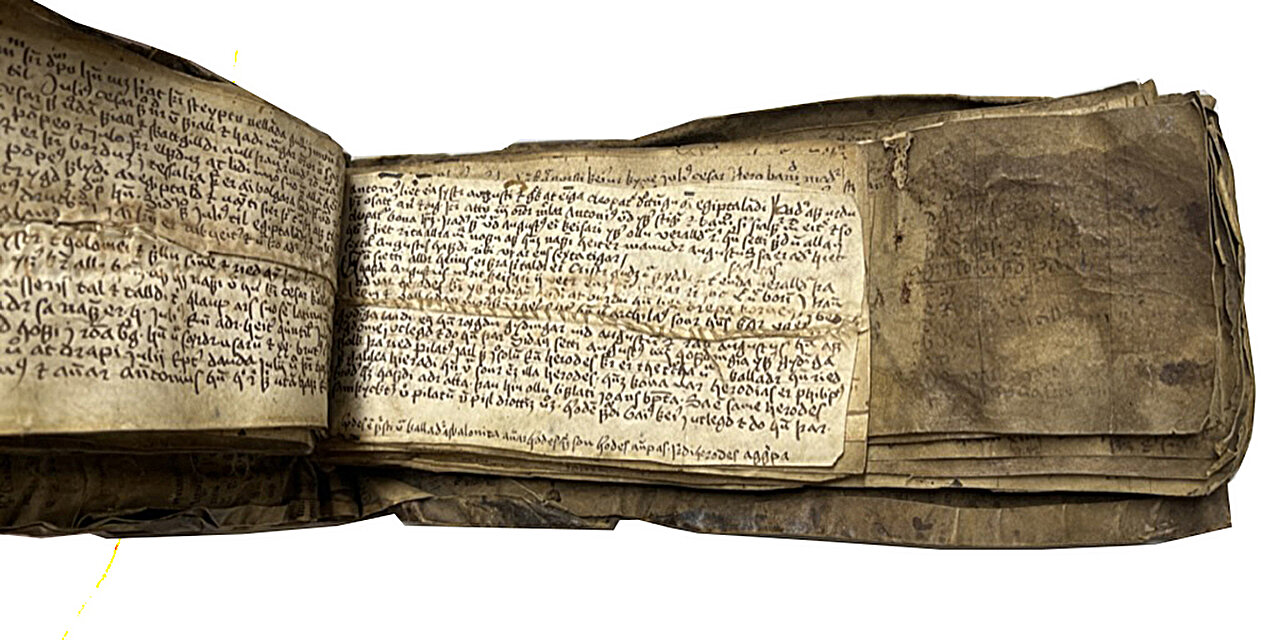

These written records were often inscribed on parchment, a durable material made from animal hides. In Iceland, calfskin was the preferred medium for creating this high-quality writing surface, known as vellum. However, vellum was expensive, requiring the skins of numerous calves to produce a single book. As a result, the material was valued immensely and repurposed when a text grew obsolete. One common method for recycling parchment involved creating “palimpsests”—pages where the original text was scraped or erased to make way for new writing. This method of conserving resources was widely practiced across Europe but became especially significant in Iceland, where materials were scarce, yet the demand for texts was high.

In some instances, entire manuscripts became tools, garments, or the structural components of newer books. Iceland’s economy and society during the medieval period necessitated these practices, but it also meant that fragments of older texts were preserved, albeit obscured, within the fabric of later documents. Over time, advances in technology have allowed researchers to decipher the remnants of these older texts through techniques such as infrared imaging, revealing a rich tapestry of historical narratives, theological discourses, and cultural details.

Another fascinating aspect of Icelandic literary tradition is its transition from Latin to vernacular Icelandic. In the Middle Ages, as in much of Europe, the Catholic Church dictated that Latin be used for liturgical and scholarly writing. However, the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, spurred by figures like Martin Luther, marked a significant shift. When Iceland adopted Protestantism between 1537 and 1550, texts began to be written in Icelandic, reflecting the growing importance of making religious teachings accessible to the general population. Many medieval Latin texts were erased to accommodate this cultural and linguistic transformation, contributing further to the palimpsest tradition.

These textual layers—fragments of Latin prayers, hymns, and sermons underneath Icelandic narratives—offer historians unique glimpses into medieval Icelandic life and its place within the broader context of European culture. Researcher Tom Lorenz, affiliated with NTNU’s Department of Language and Literature, is dedicated to uncovering these hidden histories. By reconstructing these textual fragments, Lorenz aims to illuminate the connections between medieval Icelanders and the wider European intellectual sphere.

Iceland’s literary heritage also owes much to the painstaking efforts of archivists like Árni Magnússon, an Icelander employed by the Danish monarchy in the 17th century. Magnússon sought to preserve Icelandic manuscripts, particularly those written in Old Norse, during a period when texts in these languages were increasingly tied to national pride and identity. Though his focus was primarily on Old Norse literature, he preserved many parchment fragments from Latin texts—often inadvertently, by repurposing them as covers for the books he prioritized. Today, these overlooked fragments are being reexamined to reveal the forgotten Latin heritage of medieval Icelandic literature.

Magnússon’s collection, much of which is housed in Copenhagen and Reykjavík, forms part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, signifying its global cultural importance. Since the 20th century, some manuscripts have been returned to Iceland, where they continue to be a source of study and discovery. Scholars like Lorenz, traveling across archives in Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Iceland, have identified previously unknown Latin fragments that speak to the intellectual pursuits of medieval Icelanders. These include theological texts, church music, hagiographies, and sermons—an indication that Iceland was an active participant in the religious and intellectual currents of Europe.

The roots of Iceland’s rich literary culture can be traced even further back, to the Viking Age. The sagas and poems composed during this time served as both entertainment and historical record, often blending mythology, folklore, and factual events. The literary skills cultivated during the Viking Age laid the foundation for the achievements of later medieval Icelandic writers. By mastering storytelling, poetry, and textual preservation, Icelanders secured their legacy as one of the world’s most literarily prolific nations.

Lorenz himself illustrates the enduring appeal of this tradition. Hailing from Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, a region historically connected to Denmark-Norway, Lorenz developed an early fascination with Norse mythology and Viking sagas. His academic pursuits brought him to the Center for Medieval Studies at NTNU, where he continues to uncover forgotten fragments of Icelandic literary history. His work not only sheds light on Iceland’s medieval past but also underscores the ways in which literature connects disparate cultures and eras.

Ultimately, Iceland’s literary tradition embodies a profound interplay of creativity, resourcefulness, and cultural exchange. From the vellum manuscripts of the Middle Ages to the palimpsests revealing lost Latin texts, Icelanders have consistently found ways to adapt and preserve their cultural heritage. This resourcefulness reflects the enduring spirit of a nation where storytelling remains a cherished art and an essential expression of identity. Iceland’s literature serves as a bridge between its past and present, an ongoing dialogue that continues to inspire admiration and scholarly pursuit around the world.

Reference: Tom Lorenz, Endurvinnsla og endurnýting í íslenskum uppskafningum frá miðöldum og á árnýöld, Gripla (2024). DOI: 10.33112/gripla.35.1