Researchers at Penn State University have made groundbreaking strides in understanding how certain materials store information about their past deformations, a phenomenon they liken to a “material memory.” This concept is similar to the way wrinkles form in a once-crumpled piece of paper, capturing traces of the forces that acted on it. The team’s findings could provide fresh insights into new ways of storing and recalling information in mechanical systems, opening up possibilities for everything from combination locks to next-generation computing systems.

The study, which appeared in Science Advances, unveils a special mechanism in materials that challenges established mathematical principles. This mechanism, dubbed return-point memory, can encode and retrieve information based on sequences of deformations, even under conditions where traditional theories suggest such memory storage shouldn’t be possible.

The Basics of Return-Point Memory

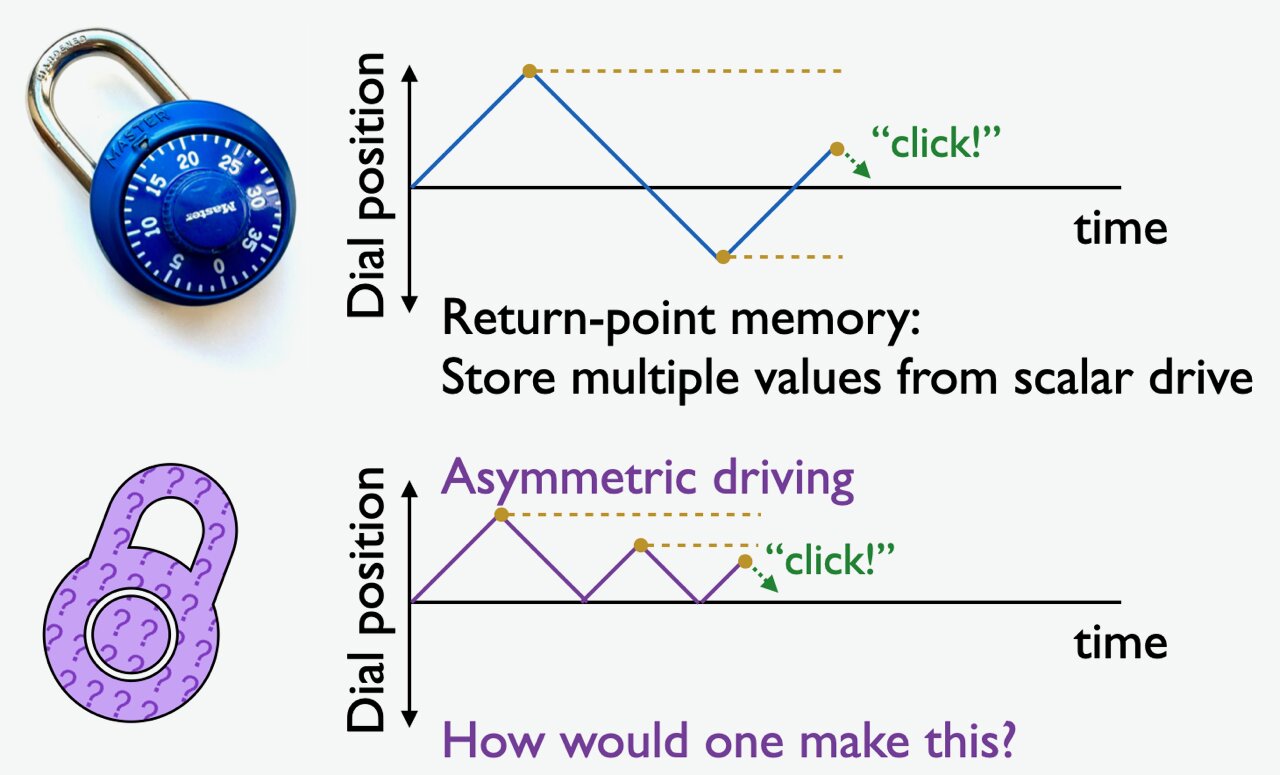

At its core, return-point memory operates in a way similar to a combination lock. In a typical lock, rotating the dial in a specific sequence—clockwise and counterclockwise—results in a final position that reflects the series of movements made. Similarly, in materials exhibiting return-point memory, the application of alternating forces (like pulling in opposite directions) can leave a “memory” of the sequence of deformations. The material will respond to these forces in such a way that its current state depends on the previous sequence of deformations, similar to how a combination lock’s dial reflects its prior positions.

This phenomenon has been observed in a range of materials and systems, from magnetic hard drives to damage in solid rock. However, previous mathematical theorems about memory formation suggest that asymmetrical forces—those that act in only one direction—should not result in sequence storage. To put it simply, just as a combination lock’s dial can’t go past zero when turned counterclockwise, a material shouldn’t be able to form a memory of a sequence if forces only act in one direction.

Yet, the Penn State team discovered a special case where this rule doesn’t hold, offering a new avenue for exploring how materials can “remember” previous deformations.

Unlocking the Mystery: Computer Simulations and Hysterons

The research team, led by Nathan Keim, associate professor of physics at the Eberly College of Science, used advanced computer simulations to investigate how materials could form and store such memories. They manipulated several factors, including the magnitude and orientation of the external forces applied to the material, as well as how the forces were generated, to explore how these variables affect memory formation. By breaking down these systems into simplified elements known as hysterons, the researchers could model how different materials respond to deformations.

Hysterons are abstract components that represent the response of a system to external forces. These elements do not immediately react to changes in external conditions and can “remember” their previous states, much like a dial on a combination lock. In the model, each hysteron has two possible states and can interact with others in two distinct ways: cooperative or non-cooperative (frustrated).

Cooperative and Frustrated Hysterons: The Key to Asymmetric Memory

Cooperative hysterons interact in such a way that a change in one element encourages a change in the other. This interaction would require symmetrical driving forces (forces alternating between positive and negative directions) to encode a sequence of deformations.

On the other hand, frustrated hysterons behave differently. These hysterons are “at odds” with each other, meaning that a change in one discourages change in the other. The researchers found that it’s this frustration between hysterons that could allow materials to store a sequence of deformations, even under asymmetric driving—forces acting in only one direction.

An analogy to this frustration is the operation of a bendy straw. When you apply a slight pull to one end of the straw, the bellows inside the straw may collapse or pop open. The key is that when one part of the system changes, it relieves stress in the other parts. In a frustrated system, such interactions prevent the system from behaving symmetrically and allow it to “remember” the sequence of events.

This finding is highly significant because it demonstrates that frustrated hysterons are the key to forming a sequence of deformations in materials subjected to asymmetrical driving forces. While it is rare to observe this behavior in real-world materials, the team’s research suggests that identifying systems with frustrated hysterons could open up new avenues for creating materials with “memory.”

Implications for Real-World Applications

Keim and his team are optimistic that their work could pave the way for designing artificial systems that store sequences of information in materials, akin to a combination lock but with far more potential applications. For instance, this could lead to innovations in mechanical systems capable of storing diagnostic or forensic information about their past, or even systems that respond to environmental conditions without the need for electricity.

One of the most promising aspects of this research is that it could lead to materials with the unique ability to store both the largest deformation and the most recent deformation in the memory sequence. This would allow the system to store and verify a series of events in a manner that could have practical applications in a range of industries, including mechanical engineering, security systems, and sensing technologies.

A Step Toward Memory in Mechanical Systems

This research also holds promise for future work in mechanical computing systems—systems that operate without electricity and could sense and respond to environmental conditions, perform computations, and adapt based on previous experiences. Keim points out that as our understanding of memory in materials deepens, the potential for mechanical systems to “think” and “remember” without traditional electronic computing methods becomes more feasible.

“One of the exciting possibilities,” Keim says, “is that we could develop systems that not only sense their environments but also compute and adapt without requiring electrical power. Understanding how to store and erase information in mechanical systems opens up new potential for technology that works outside the realm of traditional electronic-based systems.”

The researchers acknowledge that while finding frustrated hysterons in natural materials has proven challenging, their discovery gives scientists a new framework for searching for and studying materials with this rare but valuable property.

Conclusion

The recent research by the Penn State physicists highlights the power of asymmetric driving and frustrated hysterons in encoding sequences of memory in materials. This discovery challenges traditional thinking in material science and offers a glimpse into the future of mechanical information storage. As we move forward, this work could lead to a broad range of applications—from next-generation combination locks to biologically inspired mechanical systems that adapt and respond to the world around them without relying on electricity. The potential for harnessing these findings could reshape our approach to materials, information storage, and mechanical computation, offering new tools for both engineering and technology.

Reference: Chloe Lindeman et al, Generalizing multiple memories from a single drive: The hysteron latch, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr5933

Loved this? Help us spread the word and support independent science! Share now.