An international team of researchers, led by the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP) and the Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals (MUCBO | MBCN), has made an extraordinary discovery in Mallorca. They have uncovered fossil remains of a creature that lived between 270 and 280 million years ago, making it the oldest known gorgonopsian—a lineage of saber-toothed predators that are part of the evolutionary trajectory leading to mammals. The findings have been published in Nature Communications and shed light on the ancient ecosystems and evolutionary pathways of the Permian period.

Gorgonopsians are an extinct group of synapsids, a clade of animals that includes modern mammals and their ancient relatives. These creatures thrived during the Permian, between 270 and 250 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs dominated the Earth. Unlike their mammalian descendants, gorgonopsians laid eggs, and their appearance combined reptilian and mammalian traits. Warm-blooded and carnivorous, they were among the first animals to develop the iconic saber teeth, which they likely used to subdue prey. Often occupying the top of the food chain, gorgonopsians would have resembled dogs in size and body shape, though they lacked external ears and fur.

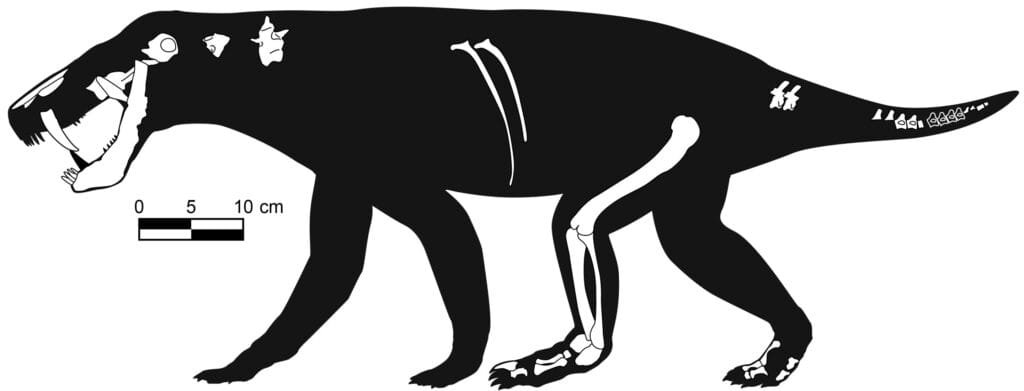

The newly discovered remains, found in Banyalbufar in the Serra de Tramuntana region of Mallorca, belong to a small-to-medium-sized individual, approximately one meter in length. This site yielded an unusually rich trove of fossils, including fragments of the skull, vertebrae, ribs, and a remarkably preserved femur. Excavations were conducted over three campaigns, resulting in an extensive collection of bones that provided a wealth of information about the animal’s anatomy, movement, and ecological role.

Rafel Matamales, curator at the Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals and lead author of the study, expressed the team’s surprise at the abundance of material recovered. “When we began the excavation, we never anticipated finding so many remains of a gorgonopsian, especially in Mallorca. The sheer number of bones—spanning various parts of the skeleton—gives us a detailed glimpse into its biology,” he remarked.

The discovery is remarkable not just because of its location but also its age. Before this, the known remains of gorgonopsians were primarily found at high latitudes, such as in Russia or South Africa. Finding such a specimen in Mallorca, which was part of the supercontinent Pangea during the Permian, expands the known geographical range of these ancient predators. Furthermore, this particular specimen predates other known gorgonopsians by several million years. Josep Fortuny, senior author and head of the Computational Biomechanics and Evolution of Life History group at ICP, highlighted the significance of this find, noting, “This is likely the oldest gorgonopsian ever discovered, at least 270 million years old, making it a pivotal piece in understanding the evolution of this lineage.”

Among the standout fossil discoveries was a nearly complete leg, which provided critical insights into the creature’s locomotion. Unlike reptiles, which typically have a sprawling gait, gorgonopsians had legs positioned more vertically beneath their bodies. This configuration represents an evolutionary step towards the more efficient movement patterns seen in mammals, allowing for better walking and running capabilities. This intermediate locomotion style underscores the evolutionary transition from reptilian ancestors to mammalian descendants.

The characteristic saber teeth found in the fossils confirm that this animal was a predator. Àngel Galobart, a researcher at ICP and director of the Museu de la Conca Dellà, explained the role of these teeth: “Saber teeth are a hallmark of large predators across ecosystems, and this gorgonopsian likely held a dominant position in its environment. Its diet would have included other animals from the ecosystem, some of which we’ve identified through fossil evidence.”

The Permian landscape of Mallorca was vastly different from the island we know today. During this period, approximately 270 million years ago, Mallorca was not an isolated island but a part of the supercontinent Pangea, situated near the equator where modern-day Congo or Guinea lie. The region experienced a monsoonal climate, alternating between wet and dry seasons. Fossil evidence suggests that the site where the gorgonopsian remains were found was a floodplain with ephemeral ponds. These ponds likely attracted a variety of animals, creating a rich ecosystem. Other species identified in this environment include moradisaurine captorhinids, ancient herbivorous reptiles like Tramuntanasaurus tiai, which may have been prey for the gorgonopsians.

The discovery of this ancient predator is a testament to the Balearic Islands’ rich paleontological heritage. Despite their small geographical size, these islands have yielded an impressive array of fossils, particularly from the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. However, fossils from earlier geological periods, such as the Permian, remain less studied. This new find adds to a growing list of remarkable discoveries, which include the world’s oldest mosquito, nearly a thousand species of ammonoids, ancestors of horses and hippos, giant sharks, and ancient coral reefs.

The implications of this discovery extend beyond understanding gorgonopsians themselves. It offers a window into a pivotal period in Earth’s history when the planet’s ecosystems were undergoing significant transformations. The Permian period was marked by the assembly of Pangea, dramatic climatic shifts, and the diversification of terrestrial life. The emergence of advanced predators like gorgonopsians highlights the evolutionary pressures and ecological dynamics of the time.

The fossils from Banyalbufar provide critical data for reconstructing the life and environment of early terrestrial ecosystems. They also serve as a reminder of the interconnectedness of life’s evolutionary history, bridging the gap between primitive synapsids and the mammals that would later dominate the Earth. This discovery, along with ongoing research, continues to deepen our understanding of life’s intricate history and the forces that have shaped it over hundreds of millions of years.

Reference: Matamales-Andreu, R., et al. Early–middle Permian Mediterranean gorgonopsian suggests an equatorial origin of therapsids. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-54425-5