Researchers from Xi’an Jiaotong University, along with collaborating institutions in China, have uncovered new insights into how sexually dimorphic dopamine circuits in the brain influence the sociosexual preferences of mice. In a groundbreaking study, they revealed that these preferences can be reversed under stress, showing how survival-related challenges alter social behavior. The paper, titled “Sexually Dimorphic Dopaminergic Circuits Determine Sex Preference,” was published in Science and provides a novel understanding of how the brain adapts socially under duress, highlighting the complex interplay between brain circuits and sociosexual choices.

Understanding Social Decision-Making in Animals

Social decision-making plays a crucial role in survival and reproduction. Animals, particularly social species like mice, must quickly assess their environment and make decisions based on interactions with others. These decisions are influenced by factors such as sex, age, and the individual’s role within the group. These choices guide social behavior—essential for cooperation, reproduction, and maintaining group dynamics.

For mammals, including humans, these decisions are also often sex-based. Interactions with individuals of the opposite sex are vital for mating and reproduction, while same-sex interactions provide essential social support, facilitating group cohesion, and sometimes even cooperation in tasks that contribute to survival. Sex-based social preferences, therefore, have an evolutionary significance, as they influence reproductive success and the cohesion of social groups.

The Role of Sexually Dimorphic Circuits

Earlier research has suggested that some instinctive behaviors in animals may rely on sexually dimorphic structures in the brain—meaning structures that differ in males and females of the same species. These neural structures often act on shared circuits, giving rise to sex-specific behaviors. While some progress has been made in understanding these mechanisms, the exact processes underlying how sex-based preferences change under stress remained unclear.

Stress is a powerful modulator of behavior, and researchers have long suspected that the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system—an important region for regulating motivation and reward—could play a central role. Dopamine circuits are well-known for regulating how animals experience and respond to pleasurable stimuli, including social interactions. However, the specific dynamics that drive shifts in social preferences under stress were previously unknown. That is, how do sex-based preferences shift, and what role does dopamine play in this process? This was the gap that the current study sought to address.

Investigating the Dopaminergic Circuitry in Mice

The team of scientists from Xi’an Jiaotong University used an innovative approach to probe the neural mechanisms involved in social preference shifts. They employed dual-color fiber photometry calcium recordings to track neuron activity, along with projection-specific chemogenetic and optogenetic manipulations to monitor and control dopaminergic neurons in the brain. Their focus was the ventral tegmental area (VTA), which plays a critical role in dopamine regulation, particularly in rewarding and social behaviors.

They examined the social preferences of male and female mice under both normal, stress-free conditions and after exposing the animals to various stressors. These stressors included chemical cues like trimethylthiazoline (TMT, which is related to predator scent), contextual fear conditioning (a method that associates specific environments with an aversive stimulus like mild shock), and auditory cues related to threat. Their hypothesis was that such stress would lead to changes in social preferences, with both male and female mice potentially shifting their preference toward interactions with same-sex individuals in response to threats.

The Effects of Stress on Social Preferences

The results were both surprising and illuminating. Under normal conditions, the mice preferred interacting with the opposite sex, with both male and female mice favoring female company. However, when the animals were exposed to stressors, their social preferences began to shift toward males. Specifically, under stress, both male and female mice spent more time interacting with males, even though, in a relaxed state, their natural preference was for females.

In males, for example, their time spent interacting with other males increased from about 34% to 56% under stress, indicating a significant preference shift. Similarly, female mice exhibited the same tendency to gravitate toward males when exposed to stress. These findings revealed that sex-based social preferences in mice are indeed flexible and can be influenced by survival stressors.

Dopaminergic Circuits and the Switch in Social Preferences

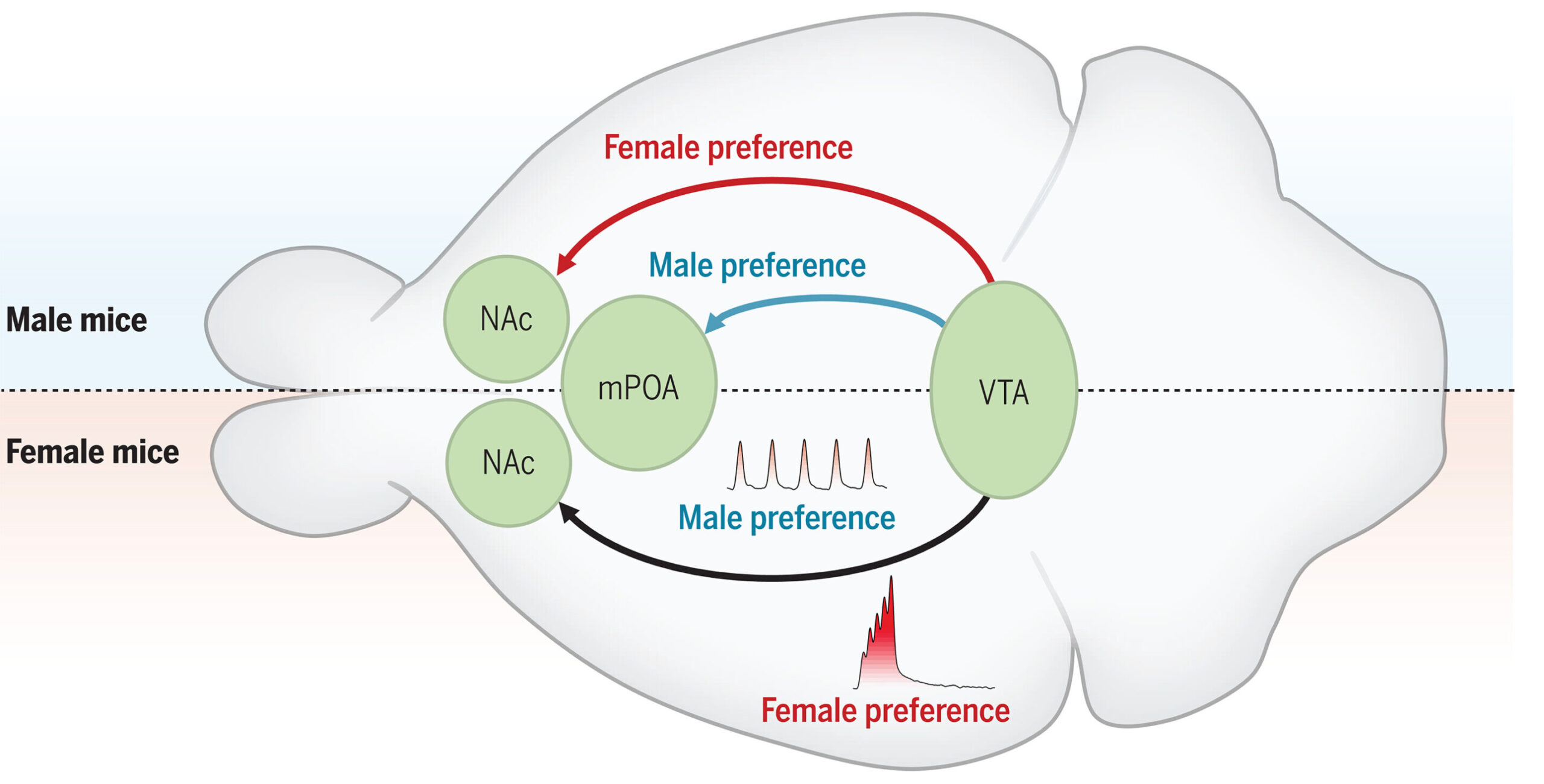

Central to the study’s findings were the altered dynamics in the brain’s dopaminergic circuits, which regulate preference behaviors. In the VTA, which projects dopamine signals to different parts of the brain, researchers identified sex-specific pathways that promoted either male or female preference under normal and stress conditions.

Two main regions of the brain were implicated in these shifts: the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the medial preoptic area (mPOA). In the absence of stress, male mice showed a strong dopamine projection to the NAc, which supported their preference for females. Female mice, similarly, relied on the NAc for female preference. However, under survival stress, activity within the mPOA, which is known for its involvement in male sexual behaviors, increased in both male and female mice. This heightened activity in the mPOA region played a major role in shifting their preference toward males.

Circuit-Specific Manipulations and Their Effects on Social Preferences

To further validate the role of these dopaminergic circuits, the scientists manipulated the activity of these pathways using chemogenetic and optogenetic techniques. By selectively activating or inhibiting VTA dopamine neurons, they were able to influence social preference behaviors.

In males, the researchers discovered that activating VTA DA neurons led to an enhanced preference for other males, a shift toward the same-sex preference that closely mirrored the effect of survival stress. Conversely, inhibiting VTA DA neurons blocked the stress-induced shift in social preference, indicating that the activation of this dopaminergic circuit was critical for the preference change.

For females, optogenetic stimulation of the VTA projections to the NAc had a fascinating effect. Rapid, burst-like activation of these neurons reinforced their preference for females. On the other hand, slower, steady patterns of stimulation increased their preference for males. This contrast demonstrated that not only the dopamine pathways but also their specific firing patterns were key to determining the direction of social preferences. Increased activity of dopamine circuits in the NAc (via D1 receptors) generally encouraged female preference, while signaling through D2 receptors in the mPOA encouraged male preference during survival stress.

Implications for the Study of Neurobiology and Social Behavior

This study underscores the profound effects of dopamine on social decision-making, demonstrating how dopaminergic circuits in the brain dynamically adjust in response to environmental stress. The findings represent a novel understanding of the brain’s flexible wiring: one that balances innate behaviors with survival-related needs. This research also highlights the complex interplay between biological predispositions (in this case, sex-based preferences) and the brain’s adaptive responses to environmental stimuli.

In addition to advancing our knowledge of social behavior and neurobiology, these insights could have far-reaching implications for the study of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. For example, conditions that disrupt normal dopaminergic function—such as schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, and mood disorders—might show atypical social decision-making behaviors in response to stress. Understanding the brain mechanisms involved in these responses may offer valuable insights into how social behaviors are altered in these conditions.

Conclusion

The study from Xi’an Jiaotong University reveals the sophisticated way in which sexually dimorphic dopamine circuits in the brain regulate social preferences in response to survival stress. Their findings reveal not only the complexity of social decision-making processes but also the remarkable adaptability of the brain’s reward systems under varying environmental pressures. By shedding light on how these neural circuits function and can be influenced under stress, the study opens up new avenues for exploring how social behavior is shaped by both intrinsic factors (such as sex differences) and extrinsic factors (like stress), with important implications for both evolutionary biology and medical research.

Reference: Anqi Wei et al, Sexually dimorphic dopaminergic circuits determine sex preference, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq7001

Bitna Joo et al, Stress drives a switch in sex preference, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu7946