A groundbreaking study led by a research team from Harvard University has revealed alarming findings about the elevated levels of organofluorine compounds in municipal wastewater across the United States. The research, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that over 60% of the extractable organofluorine in these wastewater samples originates from commonly prescribed fluorinated pharmaceuticals. Shockingly, while six federally regulated perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) comprised less than 10% of the organofluorine load, they remain part of a larger concern regarding the persistence and contamination risks posed by such chemicals.

The study brings to light a critical issue regarding the environmental and public health risks posed by organofluorine compounds, particularly those found in the widespread use of PFAS. PFAS are synthetic chemicals that contain carbon-fluorine bonds, one of the strongest molecular bonds known to science, which makes these chemicals extraordinarily stable and resistant to degradation. The robustness of these bonds gives PFAS their widely recognized nonstick properties, making them useful for a wide range of applications, including cookware, food packaging linings, waterproofing materials, and stain-resistant fabrics.

The extremely durable nature of PFAS, which does not allow the chemicals to break down in the environment, has earned them the notorious title of “forever chemicals.” This ability to persist indefinitely in the environment has caused widespread contamination across the globe. Not only are PFAS present in soil and groundwater systems worldwide, but they have even been found high on the Tibetan plateau, a result of atmospheric deposition via rainfall.

The environmental ubiquity of PFAS and other organofluorine chemicals raises alarming questions about their impact on both the ecosystems and human populations that depend on affected water sources. Once PFAS enter the environment, they pose substantial difficulties for removal, as there are currently no safe or cost-effective strategies available to effectively eliminate them from contaminated sites or wastewater systems. The chemicals infiltrate water supplies that serve millions of people, making their removal and regulation a paramount issue.

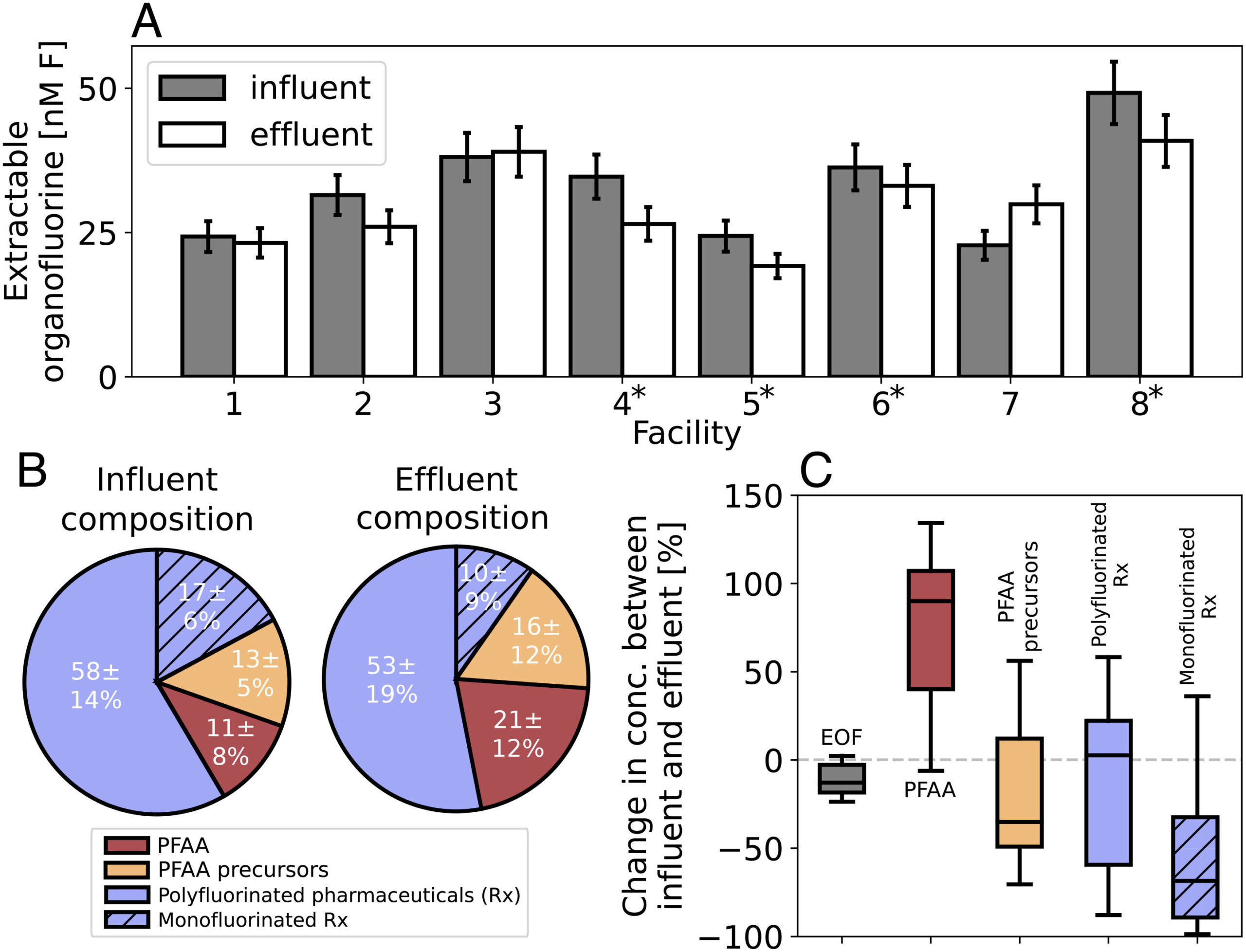

Municipal wastewater treatment facilities, which serve much of the U.S. population, have limited success in removing these harmful compounds, with fewer than 25% of measured organofluorine chemicals being extracted even through advanced treatment methods. This inadequacy is highlighted by the study’s findings, which showed that more than 60% of the organofluorine compounds in wastewater were attributed to the presence of fluorinated pharmaceuticals, while PFAS accounted for a significantly smaller portion of the detected organofluorine load, between 6% and 10%. This statistic raises an important point: though PFAS are a major concern in terms of regulation and public awareness, other sources, such as fluorinated drugs, may be contributing just as significantly, if not more, to the growing contamination issue.

The research team sampled wastewater from eight large treatment facilities across the United States, choosing facilities that had comparable design capacities to examine how organofluorine compounds varied across different regions. The results were consistent: organofluorine levels were elevated, and advanced wastewater treatment processes failed to effectively remove a significant portion of these chemicals, with removal rates not exceeding 24% in any facility. This finding is sobering because it reveals how limited our ability is to combat the persistence of these compounds once they have entered the system.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching. The researchers used a national wastewater dilution model to simulate the flow of treated wastewater as it re-enters and mixes with drinking water sources under both typical and low-flow conditions. This analysis revealed that more than 20 million Americans rely on drinking water supplies that are at risk of being contaminated with organofluorine chemicals derived from treated wastewater. For these populations, drinking water could exceed acceptable regulatory thresholds for PFAS contamination, particularly when the cumulative effects of wastewater discharges are considered.

Even though this research addresses treated wastewater, not the water consumed directly from household taps, the results highlight a larger issue: the inevitable mixing and reuse of treated water. In many communities, water sources are used multiple times in a continuous cycle, and wastewater treatment plants discharge treated water back into rivers, lakes, or groundwater supplies, from which it is later retrieved for purification and consumption. Over time, this cycle increases the risk that trace amounts of harmful chemicals, such as PFAS and other organofluorine compounds, will continue to accumulate in water systems.

For example, consider a situation in which a city taps into a river to provide drinking water. The water is purified at a treatment facility, used by the population, and the resulting wastewater is returned to the river. The water undergoes further purification, is used again, and the process repeats, with multiple municipalities or industries drawing on this same water supply. Even if the treatment processes remove some contaminants, the continuous cycle of reuse means that chemicals that are not easily removed—like PFAS—can remain present and accumulate over time. By the time water reaches a large coastal city, for instance, it may have been purified and reused countless times by upstream towns and cities, only to be treated again before being redistributed as drinking water.

The Mississippi River, which serves as a vital water source for millions of Americans across multiple states, exemplifies the complexity of this system. The river flows through over 10 states and its watershed encompasses 21 others, all reliant on the river’s water for domestic and industrial uses. Within this watershed, there are more than 4,500 publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) that manage wastewater. The sheer scale of water recycling in such systems means that the long-term effects of chemicals in the water, including PFAS and other fluorinated substances, may be far more pervasive than we realize.

These findings underscore the urgent need for more effective measures to prevent the contamination of drinking water by harmful chemicals, such as PFAS. The study calls attention to a significant environmental challenge: without advancements in water treatment technology or regulatory changes, the presence of “forever chemicals” in our water supply will continue to pose a public health threat, impacting millions of Americans’ daily lives. The persistence of PFAS and other organofluorine substances in the environment demands immediate and significant action.

Researchers stress the importance of developing better water treatment solutions that can target these persistent chemicals and more rigorously regulate the widespread use of organofluorine substances. Additionally, efforts must be made to better understand the full scope of contamination, including the role of pharmaceuticals, and to establish strategies that can effectively mitigate the environmental and public health risks associated with their accumulation in wastewater.

Reference: Bridger J. Ruyle et al, High organofluorine concentrations in municipal wastewater affect downstream drinking water supplies for millions of Americans, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2417156122

Think this is important? Spread the knowledge! Share now.