Over the past two decades, large floods have been linked to a significant increase in mortality rates from various health conditions across the United States. In fact, a recent study published in Nature Medicine reveals that deaths related to major causes of mortality were up to 24.9% higher in the period following large floods, compared to normal conditions. These findings demonstrate the widespread, hidden effects of floods, especially those unrelated to hurricanes, such as those caused by heavy rainfall, rapid snowmelt, or ice jams.

Researchers at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, along with experts from Arizona State University, Harvard University, and the University of Arizona, led the study, marking an important step in understanding how flooding impacts public health. This study aims to close a significant gap in knowledge regarding cause-specific flood mortality risks in the U.S. over time and identifies how these risks vary across different population groups.

With population growth alone projected to increase the number of people exposed to floods by 72% annually by 2050, the situation will only worsen when accounting for the additional risks posed by climate change. More frequent riverine, coastal, and flash floods are expected as storms become more severe, snowpacks melt faster, and sea levels rise. According to the researchers, flooding has already become an urgent public health issue, and it is vital to understand how its impacts affect long-term health outcomes.

“Our findings highlight that floods are associated with an increase in death rates for a range of causes, including rain-related and snow-related floods. These floods often don’t receive the same level of rapid emergency response as hurricanes do but still result in a significant rise in mortality,” explains Dr. Victoria Lynch, the first author of the study and a post-doctoral research fellow at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

For years, flooding was seen as a largely immediate threat—damaging infrastructure and forcing evacuations during or shortly after an event. However, this study, which followed over 35 million death records collected between 2001 and 2018, reveals that the effects of large floods can extend far beyond the initial disaster period, increasing mortality rates for months afterward. Using a sophisticated statistical model, the researchers compared death rates in the three months following large flood events to similar periods in non-flood years. This provided insights into how various flood-related deaths fluctuated over time.

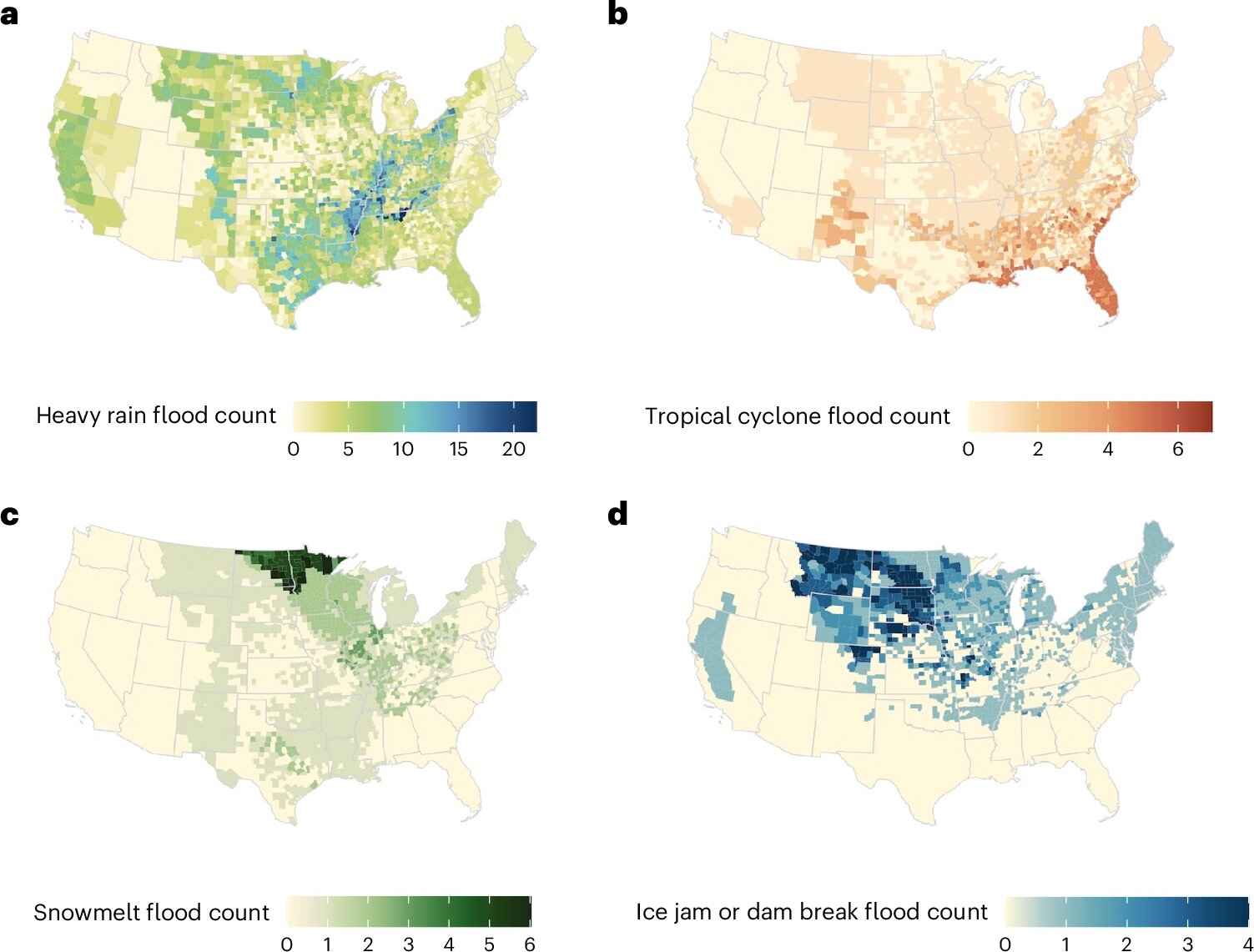

The study found that heavy rain caused the majority of flood events, with snowmelt and tropical cyclones following as other common causes in specific regions like the Midwest and Southeast United States. The analysis highlighted that injury death rates rose the most during tropical storm and hurricane-related flooding, with elderly individuals (24.9%) and females (21.2%) most at risk. When it comes to floods caused by heavy rain, the increases in mortality rates were associated with infectious diseases (3.2%) and cardiovascular diseases (2.1%). Meanwhile, snowmelt-related flooding was found to elevate death rates from respiratory diseases (22.3%), neuropsychiatric conditions (15.9%), and cardiovascular diseases (8.9%).

The study offers a unique look into how different causes of flooding have varying consequences for human health. For example, the increase in infectious disease-related deaths is likely tied to disruptions in water and sewage infrastructure, which often occurs during floods, fostering the transmission of waterborne diseases. In the case of cardiovascular and respiratory issues, such as those associated with snowmelt flooding, it is believed that stress, poor air quality, and limited access to medical care play a role. Moreover, neuropsychiatric conditions following floods might stem from the long-lasting anxiety caused by recovery efforts and long-term disruptions to daily life.

In addition to physical health issues, socioeconomic factors play an important role in determining the severity of these health risks. Communities that are more vulnerable—often those with fewer resources to evacuate, prepare for or recover from a disaster—are disproportionately affected. These groups face difficulties in managing their health during both the aftermath of flooding and subsequent recovery periods. Vulnerability, therefore, compounds mortality rates, further exacerbating the public health consequences of floods.

“While the majority of public awareness has focused on devastating events like Hurricane Katrina or Hurricane Harvey, floods caused by less obvious forces like heavy rain or snowmelt still result in long-term mortality increases,” said Jonathan Sullivan, an assistant professor of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona, and a co-author of the study. “Our study is one of the first to quantify how the impact of these floods extends over time, showing that death rates remain elevated for months after the initial flood event. This finding has critical implications for how we can prepare for future climate-related floods and adjust our public health responses.”

Previous studies focused largely on major hurricane events, and while this is valuable in understanding the broad reach of climate-related disasters, this research is novel in its approach to smaller floods, which, though less dramatic, still pose significant threats to health. The study provides valuable data showing that floods from a variety of causes lead to continued rises in mortality well after the floodwaters have receded. It underscores the importance of creating long-term public health strategies that target flood-related health risks throughout the aftermath of these events.

Flood-related diseases and death are particularly acute in the United States’ vulnerable communities. People living in socially disadvantaged groups, particularly communities of color, already experience higher rates of poor health outcomes. These same groups are more exposed to natural disasters and bear a higher burden when a flood occurs. Historical inequalities in access to health care and emergency resources contribute to these outcomes.

Further studies published by this research team have demonstrated that tropical cyclones are not only associated with higher mortality rates but also with a marked increase in the spread of waterborne diseases, which often spike in the wake of extreme weather events. These findings reinforce the need for policymakers and emergency responders to consider long-term interventions aimed at reducing health risks during and after flooding events.

This groundbreaking research emphasizes that flooding is far more than a short-term natural disaster. It has long-lasting consequences on public health that persist even months after an event. With climate change accelerating the frequency of floods and other severe weather events, understanding these persistent health risks is crucial. The study provides essential information for public health agencies, enabling them to better allocate resources, plan for future flood events, and prepare for the indirect impacts on population health.

Looking ahead, this data can help inform disaster preparedness and resilience-building efforts. The study outlines the importance of ensuring better access to clean water, reinforcing the health infrastructure to mitigate flood-related disease outbreaks, and creating plans for community-based health responses that extend well beyond the emergency phase of a disaster. More research is needed, of course, but these initial findings demonstrate the long-term and far-reaching impacts of floods on human mortality.

The research team, which includes experts from multiple institutions such as Aaron Flores (Arizona State University), Sarika Aggarwal and Rachel C. Nethery (Harvard Chan School of Public Health), and others from Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, is committed to advancing knowledge on the impacts of climate change, natural disasters, and public health, ensuring that the results of their work help societies cope with and adapt to an increasingly volatile climate. As climate change accelerates and flood events become more frequent, it is more important than ever to understand the link between floods and mortality, and to be equipped with effective strategies to protect public health.

Reference: Victoria D. Lynch et al, Large floods drive changes in cause-specific mortality in the United States, Nature Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03358-z