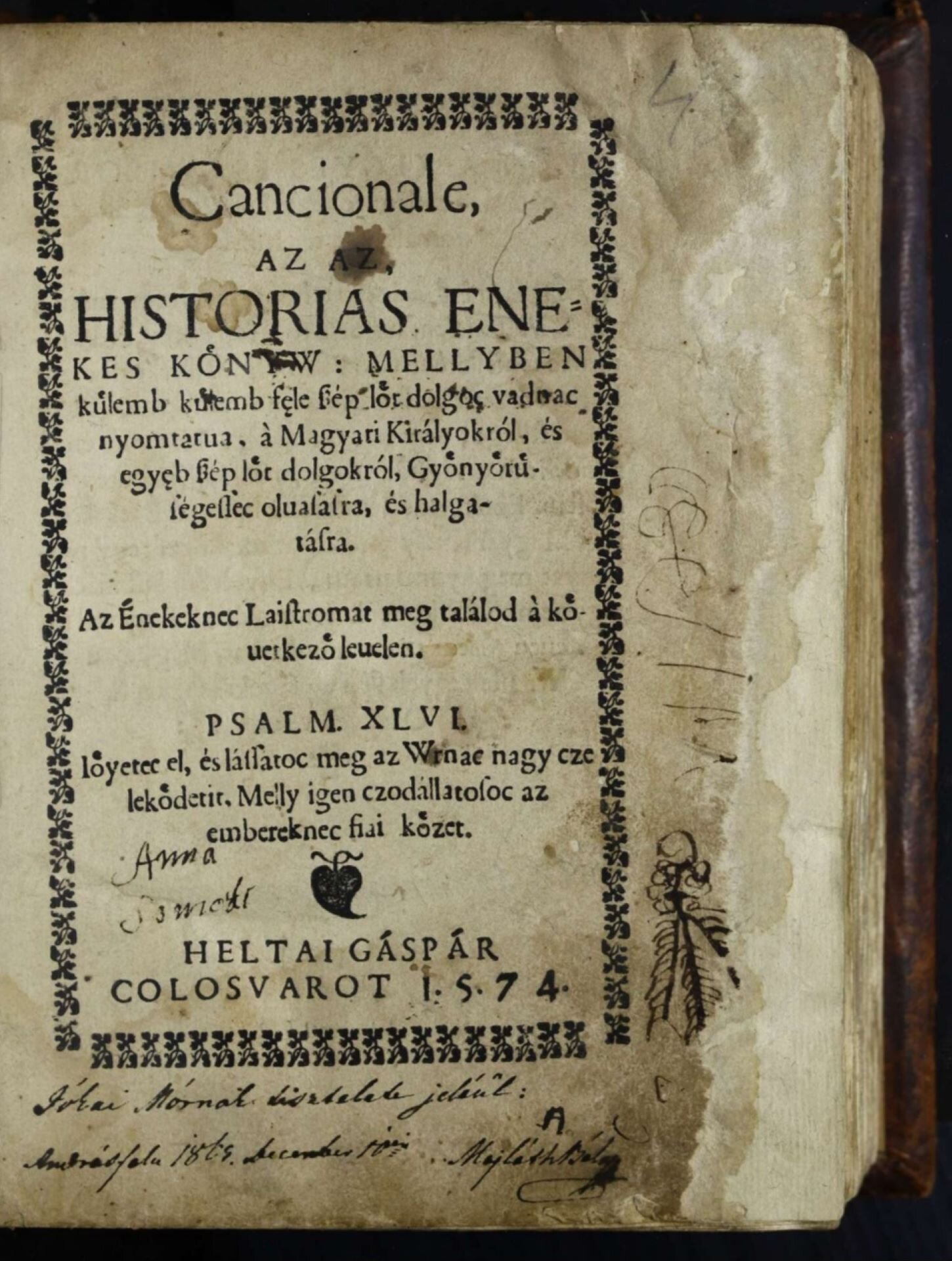

The study of past climates has long relied on natural records, such as glaciers, sediments, and pollen, collectively known as “nature’s archive.” These physical proxies provide valuable data, allowing scientists to understand climatic shifts over millennia. Yet, in recent decades, researchers have turned to another, equally rich source of information: written documents—referred to as “society’s archive.” Diaries, travel notes, parish records, and other historical accounts offer unique glimpses into the climate as experienced by people in bygone centuries.

Climate Reconstruction through Society’s Archive

These historical records can be invaluable for piecing together climate conditions and understanding their impact on human societies. As much as nature’s archives can reveal broad trends in temperature, precipitation, and vegetation, society’s archives offer a deeper, more localized view of how people experienced and adapted to their environment. In this way, written documents help fill in gaps and add nuance to the picture of the past.

One significant period in European history that highlights the interplay between written records and natural climate data is the Little Ice Age, a time of cooler global temperatures that spanned from roughly the 14th to the mid-19th century. During this period, various parts of Europe experienced significant climatic shifts, which were recorded both in scientific data and historical accounts. These accounts shed light on how people coped with climate extremes, from severe winters to intense heatwaves and flooding.

The Little Ice Age in Transylvania

While the Little Ice Age is typically associated with a cooling period, especially in the western parts of Europe, records from Transylvania reveal a different story. In the 16th century, Transylvanian climate patterns seemed to diverge from the typical cool-down of the Little Ice Age. While other regions of Europe experienced a drop in temperatures of up to 0.5°C, Transylvania recorded hotter and drier weather in the earlier part of the century.

One of the most notable climate events of the 16th century, as detailed in historical documents, was the summer of 1540. According to the society’s archive, this was an extreme event marked by intense heat and drought. A historical account from the time described how the springs dried up, rivers dwindled to mere trickles, and livestock perished in the fields. The atmosphere was thick with despair, prompting public processions where people prayed for rain. This vivid account underscores the emotional and spiritual impact that such climatic extremes had on people in the past.

Floods and Heavy Rainfall in the Late 16th Century

However, the climate in Transylvania began to shift toward more extreme weather in the latter half of the 16th century. As temperatures dropped, heavy rainfall and flooding became more frequent, particularly in the 1590s. This shift aligns with the general cooling trend observed in Western Europe, which suggests that the Little Ice Age may have manifested later in this part of Europe than in other regions.

Researcher Caciora suggests that this delay in the full impact of the Little Ice Age in Transylvania may be related to regional climatic variations. By examining both the natural climate data and written accounts, Caciora and colleagues argue that climatic changes often occurred in fits and starts, and local conditions might have moderated broader regional trends.

Climate and Catastrophes: The Human Impact

The variations in climate during the Little Ice Age were not just observed in natural phenomena. They had far-reaching consequences for human societies. Climatic extremes—whether in the form of droughts, cold waves, or flooding—led to devastating catastrophes, many of which were chronicled in contemporary records. These included periods of widespread famine, disease, and even the Black Death, which ravaged Europe for over thirty years.

The chronicler’s account of the summer of 1540 provides one example of how extreme weather could cause human suffering. But this was not an isolated event. Throughout the Little Ice Age, repeated periods of drought, famine, and disease contributed to a cycle of social and economic hardship. In total, 23 years of famine and 9 years of locust invasions are noted in the historical record, further underscoring the critical role that climate played in shaping historical trajectories.

These events highlight the deep connection between climate extremes and societal vulnerability. Weather disasters often led to large-scale migrations, as people fled from flood-prone areas or sought refuge in places that had more favorable conditions. Towns and settlements may have had to adapt by developing flood-resistant infrastructure or migrating to areas where resources were more abundant.

A New Perspective on Climate Adaptation

The societal response to these climate events also spurred technological innovation. In response to recurring droughts or flooding, communities developed more efficient irrigation systems, storage facilities, and other adaptations designed to help them cope with the changing environment. Some towns implemented changes in their urban planning, building new infrastructure to protect against future natural disasters.

Caciora points out that these written records offer a human-centered perspective on climate events. They tell us not only about the weather but about how people perceived and responded to those conditions. Chronicles and diaries provide a window into the emotional and psychological impacts of living through climatic extremes—an aspect of climate history often overlooked in purely scientific records. These documents allow us to understand how people not only adapted but also endured the hardships that nature imposed on them.

The Limitations of Society’s Archive

While the societal archive offers valuable insights into past climates, it is not without its limitations. For one, literacy was not widespread during the 16th century, so the number of records available is limited. Additionally, many records were written from a highly subjective perspective, with emotions and personal biases coloring the observations. Local-scale reports could vary widely depending on where the records were kept and who wrote them. In fact, Caciora’s research highlights gaps in the available data—some periods, such as around 15 years in the 16th century, lack any reliable records or contain contradictory accounts that make them difficult to interpret.

Furthermore, the reliance on subjective accounts means that it can be difficult to extract precise climate data. For example, a chronicler might describe a particularly cold winter or a severe drought, but the descriptions can be vague or overly dramatic, making it hard for modern scientists to quantify exactly how extreme these events were compared to what we know about climate today.

Nevertheless, despite these challenges, the societal archive remains an invaluable resource. These written records are not meant to replace natural proxies but to complement them, offering a richer, more nuanced view of how climate shaped human history.

Relevance for Modern Climate Resilience

Studying the past provides important lessons for understanding the socio-economic consequences of extreme weather events. Researchers today are increasingly aware of the role that climate plays in shaping human history, and the information gleaned from society’s archive is crucial for developing more effective strategies for climate resilience.

For modern societies facing the growing threat of climate change, these historical records offer insight into how past populations responded to climate-related disasters and what adaptive strategies were employed. By understanding how people coped with extreme weather in the past, we can better prepare for future challenges.

Caciora emphasizes that, as we confront the impacts of global warming, understanding past human responses to climatic stressors can help inform our own resilience strategies. The historical documents are a powerful reminder that human societies are not passive victims of the environment—they actively respond and adapt, shaping their future paths in the process.

Conclusion

The combination of nature’s and society’s archives provides a richer, more complex picture of how climate has influenced human societies over the centuries. While natural proxies reveal long-term shifts and trends, written records bring to life the personal experiences of people living through those changes. By examining both, we can build a more comprehensive understanding of past climates and their societal impacts. This not only helps us understand history but also equips us with valuable insights for addressing the climate challenges of today and the future.

As we continue to face climate extremes and global warming, these historical records remind us of the importance of resilience and adaptation, both at the individual and societal levels.

Reference: Reconstruction of climatic events from the 16 th century in Transylvania: Interdisciplinary analysis based on historical sources, Frontiers in Climate (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fclim.2024.1507143