In the quiet, climate-controlled archives of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands, a sharp-eyed biologist spotted something strange—something colorful glinting inside the casing of a tiny, preserved insect larva. The larva belonged to a caddisfly, a moth-like insect that spends the early part of its life submerged in freshwater streams, sheathed in an intricate homemade armor of scavenged materials. But this particular casing was not made entirely of pebbles, leaves, or grains of sand. It had a startlingly modern twist: a sliver of synthetic plastic.

This chance observation would trigger a deep dive into one of the world’s most insidious environmental issues—microplastic pollution—and yield a surprising conclusion: caddisfly larvae have been incorporating microplastics into their protective homes since at least the early 1970s, unknowingly documenting the onset of a global environmental crisis.

Caddisflies: Nature’s Underwater Engineers

To appreciate the magnitude of this discovery, it’s worth understanding the remarkable behavior of the caddisfly larva. These unassuming creatures, found in freshwater ecosystems worldwide, are natural engineers. After hatching, the larvae build protective cases around themselves using whatever materials are available in their immediate surroundings—bits of twigs, sand grains, tiny stones, or leaf fragments. These cases are not just for camouflage; they also shield the soft-bodied larvae from predators like fish and birds.

Each case is a masterclass in miniature architecture—form follows function, shaped by instinct and necessity. But what happens when the available building blocks include not just natural elements, but tiny fragments of plastic?

An Accidental Archive of Pollution

The team of biologists at Naturalis didn’t set out to study pollution. In fact, their work began with a simple curiosity about the collection of 549 caddisfly larva casings, preserved meticulously over decades. But that one unexpected glint of plastic in a casing from the 1980s changed everything.

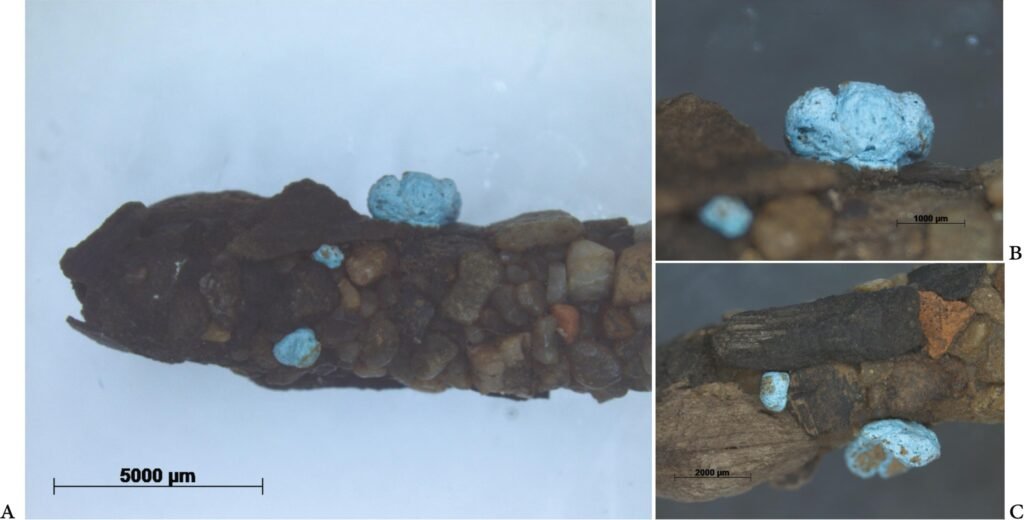

Curiosity gave way to systematic analysis. Using microscopy and chemical testing, the researchers began examining the museum’s collection. They uncovered microplastic particles—blue, yellow, and other hues—embedded in the larvae’s protective sheaths. Some were unmistakably synthetic, showing clear signs of man-made origin. Even more alarmingly, the team found chemical additives like lead, titanium, and zinc, which are often added to plastics for durability or color enhancement.

One casing from 1986 had several specks of blue plastic, clearly discernible among the natural materials. Even more jaw-dropping was a casing dated to 1971—containing bright yellow microplastic, providing one of the earliest pieces of physical evidence that microplastics had infiltrated even the most humble corners of freshwater ecosystems.

Microplastics: Ubiquity in a Modern Age

Microplastics are particles smaller than five millimeters, often invisible to the naked eye, and can come from degraded plastic items, clothing fibers, cosmetics, or industrial byproducts. Since mass plastic production took off in the mid-20th century, these particles have steadily accumulated in our oceans, lakes, rivers, and even mountaintops.

But rarely has their long history been recorded in such a tangible, biological archive. The caddisfly larvae, in their desperate search for building material, unwittingly began incorporating these tiny, colorful invaders into their bodies’ protective armor. In doing so, they left behind a unique time capsule, chronicling pollution across decades—one tiny casing at a time.

The significance of this discovery lies not just in the presence of microplastics, but in the timeline. It pushes the documented spread of microplastics into freshwater ecosystems back over 50 years, decades before public awareness of plastic pollution became widespread.

Danger in the Details: How Plastic Could Alter Survival

While the sight of plastics woven into larval casings may seem like an odd novelty at first, it’s far more than that. The presence of microplastics in larval cases could fundamentally alter survival dynamics in aquatic environments.

The researchers observed that plastic particles were often more colorful and reflective than natural materials—potentially making the larvae more visible to predators like fish and birds. Worse, plastics tend to be more buoyant, potentially lifting the larva slightly in the water column and making them easier to spot.

From a biological standpoint, this is a serious disadvantage. The entire purpose of the casing is stealth and protection. A brightly colored, plastic-laced home may be a death trap, increasing the larvae’s vulnerability to predation.

Moreover, the chemical additives found—such as lead, titanium, and zinc—are not benign. These metals can leach into the water or the organisms themselves, causing developmental or physiological damage, though the exact impact on caddisfly larvae remains to be fully understood.

Environmental Ripples: Are Other Species Affected Too?

The implications of this research ripple out far beyond the caddisfly. If these tiny, sensitive insects have been interacting with microplastics since the 1970s, what about other freshwater organisms? The study hints at a broader ecological footprint. It’s highly likely that other invertebrates, especially those that scavenge or build with environmental materials, have also incorporated plastic into their life cycles—perhaps affecting behavior, development, and reproduction in subtle ways we are only beginning to detect.

This study also invites a reevaluation of museum collections and biological archives. Preserved specimens from decades past may harbor silent evidence of anthropogenic pollution. By analyzing them with modern technology, scientists can build timelines, detect trends, and reconstruct environmental changes that were invisible to observers at the time.

The Unseen Historians of Pollution

What’s perhaps most poetic—and most chilling—about this discovery is the role the caddisfly larvae played as accidental historians. In their pursuit of survival, they chronicled the encroachment of plastic into the natural world. Their casings became a record of human impact, not through intention, but through necessity and instinct.

They built with what they found. And what they found—beginning at least 50 years ago—was plastic.

This biological documentation highlights the pervasiveness of microplastics, not just in oceans but in freshwater systems, not just in industrial zones but in nature’s quiet corners. It’s a sobering reminder that pollution doesn’t always announce itself with oil slicks and smoke. Sometimes, it seeps into the delicate architecture of a larva’s home.

A Call to Action, Hidden in a Shell

This study is not just about caddisflies. It’s about how deeply and quietly human activity infiltrates nature, often without our awareness. It’s about how tiny particles, invisible to most eyes, accumulate over decades to form a mosaic of unintended consequences. And it’s about how even the smallest creatures can reflect back to us the scale of our actions.

As the research concludes, there’s a potential silver lining. By recognizing the role of preserved organisms in tracing environmental history, we can more precisely track the timeline of pollution, identify vulnerable species, and develop targeted conservation strategies.

But there’s also a cautionary tale here—one that requires immediate attention. The plastic pollution crisis is not new, and it’s not confined to oceans or floating garbage patches. It is everywhere, etched even into the lives of insects at the bottom of a freshwater stream. And it has been that way for longer than most of us ever imagined.

Reference: Auke-Florian Hiemstra et al, Half a century of caddisfly casings (Trichoptera) with microplastic from natural history collections, Science of The Total Environment (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2025.178947