The detection of gravitational waves (GWs) in 2015 was a landmark moment in astrophysics, providing a groundbreaking new way to observe the universe. These ripples in space-time, predicted by Albert Einstein more than a century ago, offered an unprecedented look at some of the most extreme cosmic events, like the merging of black holes. Before this discovery, astronomy was largely limited to electromagnetic radiation—light in all its forms—from radio waves to gamma rays. But gravitational waves are fundamentally different, offering a glimpse into the universe in a way that light cannot.

As researchers continue to explore the potential of gravitational waves, a fascinating question arises: Could we use them for communication, in a way similar to how we currently use electromagnetic waves, such as radio waves? While this concept might seem futuristic or beyond our reach today, it’s a line of inquiry that is gaining traction. New research, notably the paper “Gravitational Communication: Fundamentals, State-of-the-Art and Future Vision,” delves into the possibilities of gravitational wave communication (GWC), suggesting that while the technology is not yet feasible, it holds considerable promise for the future.

The Challenge of Traditional Communication

Currently, our communication systems rely heavily on electromagnetic waves, including radio, microwaves, infrared, and visible light. These waves work well for a variety of applications, but they have significant limitations. For one, electromagnetic signals weaken as they travel over long distances. In addition, they can be distorted by atmospheric effects, solar radiation, and space weather. Signals are also limited by line-of-sight—obstructions in the environment can prevent signals from reaching their destinations. These limitations are especially pronounced when attempting to communicate across vast distances, such as in deep space.

In contrast, gravitational waves are a different type of wave, created by the movement of massive objects through space-time. Unlike electromagnetic waves, gravitational waves can pass through virtually any matter without being absorbed or scattered. This characteristic makes them an attractive option for future communication, especially for transmitting information over long distances in the harsh environments of space.

Advantages of Gravitational Wave Communication

One of the most compelling advantages of gravitational wave communication (GWC) is that these waves are robust in extreme environments. Whether it’s the vacuum of space or a dense astrophysical region around a supermassive black hole, gravitational waves can travel vast distances without losing significant energy. In contrast, electromagnetic signals can be disrupted or even blocked by interstellar matter, such as cosmic dust and gas.

In addition to their resilience, gravitational waves would be less susceptible to the kinds of distortions that plague electromagnetic waves. Diffusion, distortion, and reflection are common issues when using radio waves or light for communication. These problems could potentially be avoided with GWC, leading to clearer, more reliable transmission.

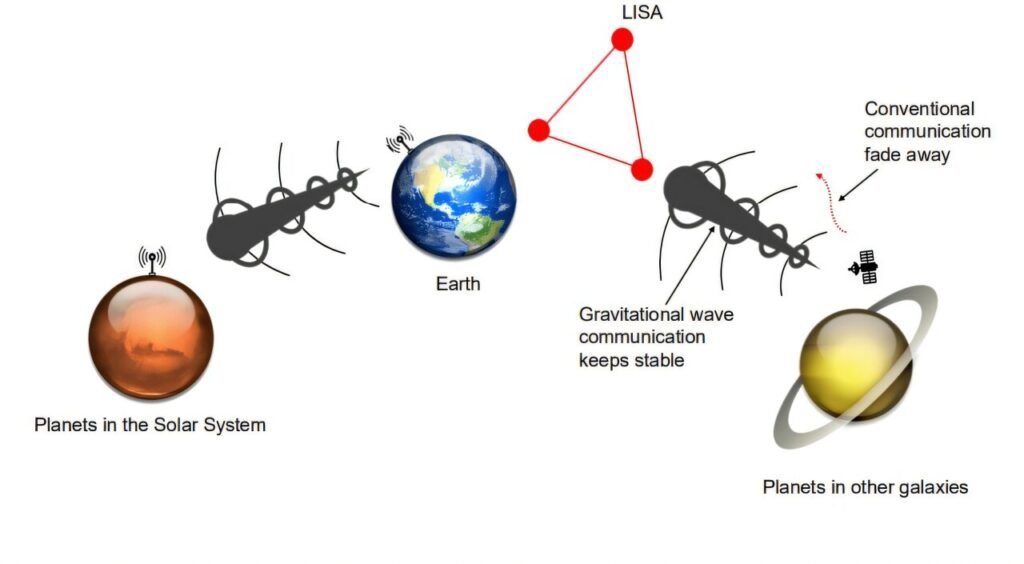

Gravitational wave communication also holds promise for space exploration. Electromagnetic signals struggle to maintain their strength over extremely long distances, and their quality deteriorates as they pass through cosmic phenomena. In contrast, GWC could allow for consistent signal quality, even for missions traveling beyond our solar system.

The ability to leverage naturally occurring gravitational waves could also make GWC more energy-efficient. Gravitational waves are often generated by extreme astrophysical events, such as the collision of black holes or the merger of neutron stars. Harnessing these natural events could eliminate the need for large amounts of energy to create the waves artificially, reducing the overall costs of GWC technology.

The Road to Practical Gravitational Wave Communication

Despite the theoretical appeal of GWC, the technology to generate and detect gravitational waves strong enough for communication is still in its infancy. Gravitational waves are incredibly weak, and detecting them requires highly sensitive equipment, like the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which detected the first gravitational waves from a black hole merger in 2015. However, these signals are only detectable under extreme conditions, such as when supermassive black holes (with masses billions of times that of our Sun) collide. The waves produced by these events are often too weak to be observed directly or to be used for communication.

Generating gravitational waves strong enough to be used for communication is a significant challenge. As the paper by Houtianfu Wang and Ozgur B. Akan from the University of Cambridge explains, there are several potential methods to create these waves, including mechanical resonance, rotational devices, superconducting materials, and high-power lasers. However, even the most promising techniques so far have not been able to generate waves that are strong enough to be detected or used in communication.

One of the primary obstacles is that only enormous masses moving at extremely high speeds—such as black holes or neutron stars—can generate detectable gravitational waves. As a result, creating artificial waves of similar strength in the lab remains one of the most significant hurdles for GWC.

Exploring Methods for Artificial Gravitational Wave Generation

In the past, researchers have proposed several methods to generate gravitational waves, including rotating masses, piezoelectric crystals, superfluids, and particle beams. However, these methods have faced several challenges, including the difficulty of achieving the necessary mass and velocity to generate detectable waves. Even when gravitational waves were theoretically produced in these experiments, their amplitude was often too low to be detected by current instruments.

As the paper notes, high-frequency gravitational waves, which might be easier to generate under laboratory conditions, remain undetectable because their amplitudes are too small, and the frequencies don’t align with existing detector sensitivities. Thus, while there has been progress in the theoretical development of GWC, more work needs to be done to develop practical methods of creating and detecting gravitational waves for communication.

The Future of Gravitational Wave Detection and Modulation

Another critical aspect of GWC is the need for advanced detection technologies. Current gravitational wave detectors, such as LIGO, are designed to detect the waves produced by astronomical events like black hole mergers. These detectors, however, are not optimized for GWC applications, which require the ability to detect waves at different frequencies and amplitudes.

Researchers need to design new types of detectors that are capable of operating across a broader range of frequencies and sensitivities. Developing these new instruments will be crucial for enabling the practical use of GWC in communication systems.

In addition to detecting gravitational waves, scientists will also need to figure out how to modulate them to carry meaningful information. Traditional communication systems, such as AM and FM radio, rely on modulating electromagnetic waves to encode information. Similarly, GWC will require methods to modulate gravitational waves so that they can be used for communication.

Several modulation techniques have been proposed, including amplitude modulation (AM) and frequency modulation (FM), using astrophysical phenomena or dark matter. For example, the paper discusses the potential for using dark matter-induced frequency modulation to encode information on gravitational waves. However, the properties of dark matter remain largely unknown, and more research is needed to understand how it could be harnessed for communication.

Overcoming Challenges: Attenuation and Noise

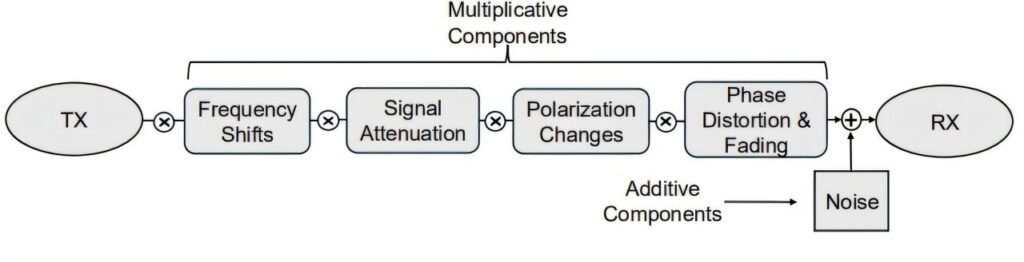

Despite its potential, GWC is not without challenges. Attenuation, or the gradual loss of signal strength over distance, remains a significant issue. As gravitational waves travel through dense matter, magnetic fields, and cosmic structures, they can experience phase distortion, polarization shifts, and other forms of interference. These factors could degrade the signal quality, making it harder to decode and process the information.

In addition to attenuation, there are unique sources of gravitational noise, such as thermal gravitational noise and background radiation, which could interfere with the detection and interpretation of GWC signals. To address these issues, researchers must develop comprehensive channel models to account for all the potential noise sources and ensure reliable and efficient detection.

Looking Ahead: The Promise of Gravitational Wave Communication

While the development of practical gravitational wave communication systems remains a long-term goal, the potential benefits are immense. GWC could offer a solution to the communication challenges faced in deep space exploration, where electromagnetic waves often struggle to maintain their strength over long distances. For missions beyond the solar system, where traditional communication systems are not viable, GWC could provide a reliable and robust method for transmitting data.

The idea of using gravitational waves for communication is still in its infancy, but the theoretical groundwork has been laid, and researchers are optimistic about future developments. As Wang and Akan conclude in their paper, “Gravitational communication, as a frontier research direction with significant potential, is gradually moving from theoretical exploration to practical application.”

Although there is much work to be done, GWC holds promise as a revolutionary communication method that could reshape how we transmit information across space and even between distant galaxies. As research continues to evolve, it is likely that we will witness breakthroughs that bring this futuristic idea closer to reality.

Reference: Houtianfu Wang et al, Gravitational Communication: Fundamentals, State-of-the-Art and Future Vision, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2501.03251