The study of exoplanets has led to remarkable discoveries, revealing that nearly one-third of known exoplanets are gas giants, similar to Jupiter or Saturn. These massive worlds, often composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, are a mainstay in planetary systems across the galaxy. However, while our solar system hosts gas giants far from the sun, some distant planetary systems harbor what are known as “hot Jupiters” and even “ultra-hot Jupiters”—gas giants that orbit dangerously close to their stars, sometimes as close as Mercury is to the Sun. These planets endure extreme temperatures, often hotter than the surface of a star, leading to their playful nickname, “roasting marshmallows.”

Hot Jupiters are not just extraordinary for their proximity to their stars and blistering heat; they also offer a unique opportunity to probe the early formation of planetary systems and the characteristics of the protoplanetary disks that gave birth to them. Peter Smith, a Graduate Associate at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, is one of the researchers helping to unravel the mysteries of these planets. As a member of the aptly named Roasting Marshmallows Program, Smith and his team focus on studying the atmospheric chemistry of these extreme planets, hoping to glean insights into their formation and the conditions of their birthplaces.

The Role of IGRINS in Understanding Hot Jupiters

The program employs cutting-edge instruments to study exoplanet atmospheres. One key tool is the Immersion GRating INfrared Spectrograph (IGRINS), which is housed at the Gemini South Telescope in Chile, part of the International Gemini Observatory operated by NSF NOIRLab. IGRINS is designed to capture high-resolution infrared spectra, allowing astronomers to identify and measure the chemical composition of exoplanet atmospheres. This capability is crucial for understanding how planets like WASP-121b—one of the most well-known hot Jupiters—came to be.

WASP-121b is a gas giant that orbits its star at an extremely close range, making it an ideal target for study. Despite its size and extreme conditions, the planet’s atmosphere has revealed key details about its formation that challenge current models of planetary development.

Unraveling the Formation History of WASP-121b

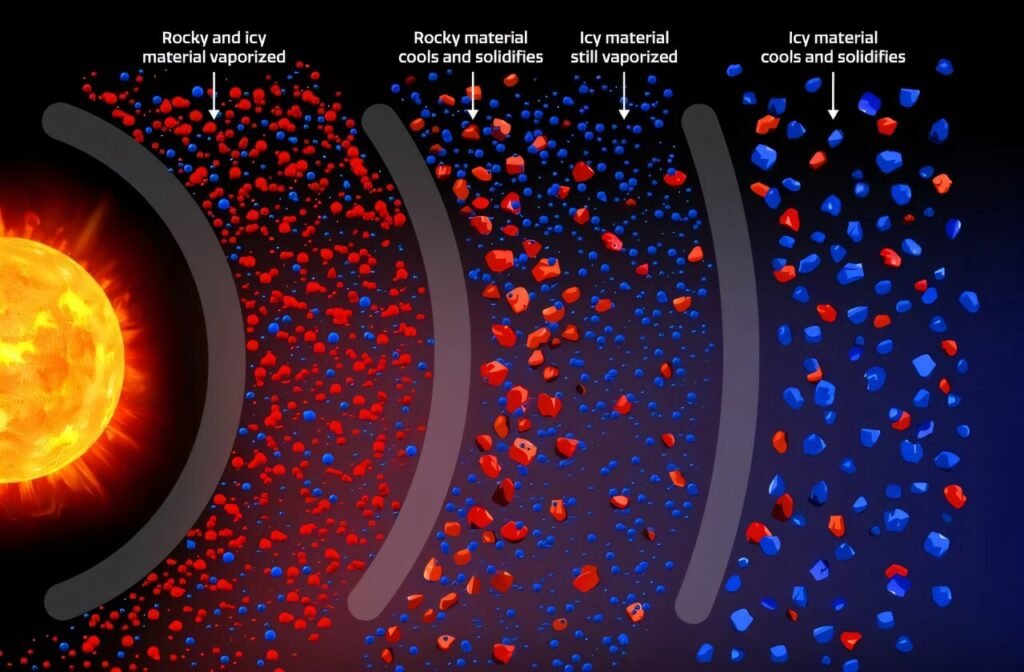

Planetary systems generally form from a protoplanetary disk, a vast, rotating disk of gas and dust that surrounds a young star. This disk consists of a mix of solid, rocky materials like iron, magnesium, and silicon, as well as lighter, volatile compounds such as water, methane, ammonia, and carbon monoxide. The composition of the disk is not uniform; instead, it varies depending on temperature. Rocky materials, which have high melting points, condense and solidify in the cooler, outer regions of the disk. Meanwhile, ices and gases, which have lower condensation temperatures, dominate in the warmer, inner regions.

When a planet forms, it accumulates material from the disk, and the mix of rock and ice in its composition provides important clues about where in the disk the planet originated. Typically, gas giants form in regions that are cold enough for ices to condense, providing the solid building blocks necessary for their growth.

However, the research team led by Smith recently made an unexpected discovery about WASP-121b. Their analysis of the planet’s atmospheric composition, based on data obtained with IGRINS, revealed that WASP-121b has a high rock-to-ice ratio. This suggests that the planet formed in a part of the protoplanetary disk that was too hot for ices to condense, a surprising finding that challenges previous models of gas giant formation.

Typically, it has been assumed that gas giants need solid ices to form, but WASP-121b’s composition suggests a different formation scenario, possibly pointing to the presence of rocky material even in the warmer regions of the disk. Smith himself notes that this discovery might require a reevaluation of how we think about the conditions necessary for gas giant formation.

A Unique Method for Measuring Rock-to-Ice Ratios

Measuring the rock-to-ice ratio of exoplanets typically involves a two-step process: one instrument is used to detect solid, rocky materials in visible light, while another captures the infrared signature of gaseous, icy elements. However, because WASP-121b is an ultra-hot Jupiter with extreme surface temperatures—up to 2,500 degrees Celsius—both solid and gaseous materials are vaporized into the atmosphere. This makes it possible to measure both the rocky and icy components in a single observation, something that had not been done before.

Smith and his team used IGRINS to obtain a high spectral resolution of the planet’s atmosphere, allowing them to detect the vaporized rock and ice components simultaneously. This breakthrough in observational technology eliminated the need for multiple instruments and reduced the potential errors associated with using different telescopes and spectrometers. In fact, Smith claims that data gathered by IGRINS provided more precise measurements of the individual chemical abundances in WASP-121b’s atmosphere than could have been achieved using space-based telescopes.

This technique could represent a major leap forward in exoplanetary research, as it allows scientists to obtain more accurate atmospheric compositions from a single source, which could help refine the models of planet formation that currently dominate the field.

Extreme Climates and the Unusual Weather of WASP-121b

In addition to uncovering clues about WASP-121b’s formation, Smith and his team have also gained remarkable insights into the planet’s atmospheric dynamics. As expected from a planet so close to its star, the climate of WASP-121b is extreme—far from anything seen on Earth. The planet’s dayside is hot enough to vaporize elements that are typically considered “metals,” such as iron, titanium, and magnesium. These vaporized metals can be detected through spectroscopy, revealing the unique chemical makeup of the planet’s atmosphere.

Winds on WASP-121b carry these metals from the blistering dayside to the nightside, where the temperatures are cooler. This temperature differential causes the metals to condense and rain out on the nightside, an effect that Smith and his team were able to observe as calcium rain. Such an extreme form of weather is unprecedented, and the ability to study these phenomena gives researchers a fascinating view into the dynamics of an exoplanet’s atmosphere.

The data from IGRINS allowed Smith’s team to study the planet’s weather in detail, including wind speeds and other atmospheric features. As IGRINS continues to improve, scientists hope to probe even more subtle atmospheric dynamics, helping to answer questions about the behavior of exoplanet atmospheres in extreme environments.

The Future of Exoplanet Research with IGRINS-2

IGRINS was so successful in its observations of WASP-121b that it led to the development of a new version of the instrument: IGRINS-2. The new iteration, now installed at the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii, is currently in its science calibration phase. IGRINS-2 promises even greater sensitivity and precision, which will allow astronomers to extend their studies to more exoplanetary systems. As the next generation of instruments continues to improve, the ability to study hot and ultra-hot Jupiters with unprecedented detail will continue to expand.

Smith and his team plan to apply these advances to investigate other exoplanets, building a larger sample of hot and ultra-hot Jupiter atmospheres. By analyzing the chemical composition, weather patterns, and formation histories of these extreme planets, researchers will refine our understanding of how giant planets form and evolve. In the long term, this research could help answer some of the most fundamental questions about the diversity of planetary systems and the conditions required for planet formation across the universe.

Conclusion

The study of exoplanets like WASP-121b is opening new frontiers in our understanding of planetary formation and atmospheric chemistry. With cutting-edge instruments like IGRINS and IGRINS-2, scientists are now able to measure rock-to-ice ratios, probe atmospheric dynamics, and even detect strange weather phenomena on faraway worlds. These discoveries challenge our assumptions about how gas giants form and what conditions are necessary for their creation. As we continue to study these roasting marshmallow planets, we may find that the process of planetary formation is far more complex—and far more varied—than we ever imagined.

Reference: Peter C. B. Smith et al, The Roasting Marshmallows Program with IGRINS on Gemini South. II. WASP-121 b has Superstellar C/O and Refractory-to-volatile Ratios, The Astronomical Journal (2024). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ad8574