Dark matter, an elusive and mysterious component that makes up a significant portion of the universe’s mass, continues to confound scientists. Despite its gravitational effects being evident in the movement of galaxies and galaxy clusters, researchers have yet to directly detect this matter or determine its composition. The search for dark matter has led to various theoretical candidates, one of the most promising being light dark matter (LDM).

LDM refers to hypothetical particles with relatively low masses, typically below a few giga-electron volts (GeV/c²), which are thought to interact weakly with ordinary matter. Due to the nature of these weak interactions, detecting LDM has been an immense challenge, requiring highly sensitive detectors and innovative approaches. A new study led by the NEON Collaboration, based in South Korea, has provided fresh insights into the detection of LDM, pushing the boundaries of experimental research in this area.

The Search for Light Dark Matter

Light dark matter particles are theorized to have mass ranges between 1 keV/c² and 1 MeV/c², a domain that had previously remained largely unexplored in direct dark matter detection experiments. These particles are believed to interact weakly with normal matter, which makes them incredibly difficult to identify. However, scientists have been developing ways to detect such elusive particles by looking for their faint interactions with electrons.

The NEON (Neutrino Elastic Scattering Observation with NaI) collaboration, a research group working with a specially designed detector near the Hanbit nuclear reactor in South Korea, has published significant results in the quest to detect light dark matter. Their recent findings, detailed in a paper in Physical Review Letters, present new constraints on the properties of LDM particles, shedding light on how these particles might interact with matter and informing future research.

The NEON Experiment: A New Approach to Dark Matter Detection

The NEON collaboration‘s groundbreaking approach takes advantage of the unique environment provided by a nuclear reactor, which emits an abundance of high-energy photons. The researchers hypothesized that these photons could be converted into dark photons, a theoretical particle that could interact with LDM. When dark photons decay, they might produce interactions that could be detected.

“We were inspired by the idea that nuclear reactors, which emit a significant number of high-energy photons, could provide a natural setting for testing dark matter theories,” said Hyunsu Lee, co-author of the paper, in an interview with Phys.org.

The primary goal of the NEON experiment is to look for LDM-electron interactions—where light dark matter particles might interact with electrons and produce detectable signals. To do so, the experiment used a highly sensitive detector located in close proximity to the Hanbit nuclear reactor, specifically designed to identify the subtle signs of these interactions.

The Hanbit reactor produces a significant amount of high-energy photons, which are a key component in the process. These photons are thought to potentially interact with electrons, converting into dark photons, which in turn could decay into light dark matter particles. Detecting such interactions, though, requires sophisticated technology and a well-calibrated environment, as these signals are faint and easily drowned out by background noise.

Key Findings and Methodology

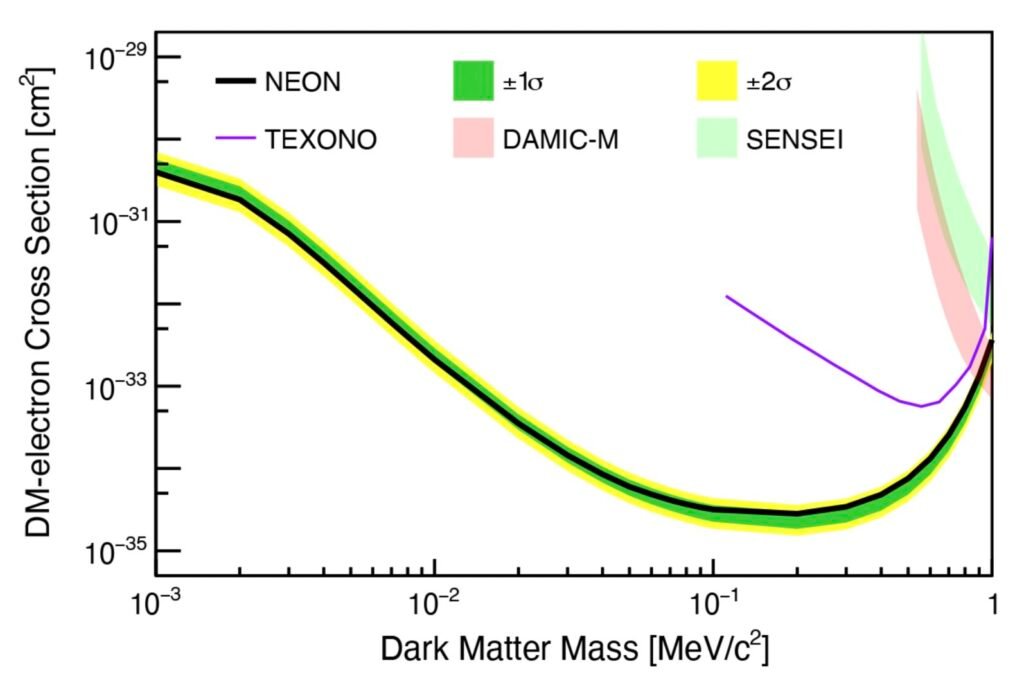

In their first round of experiments, the NEON collaboration focused on searching for LDM particles with masses between 1 keV/c² and 1 MeV/c². This range was previously unexplored in direct detection experiments, as most dark matter research had been focused on heavier candidates. By exploring this new territory, the team sought to expand the boundaries of what could be achieved through reactor-based experiments.

“With this first run of the experiment, we aimed to probe a new and uncharted mass range for light dark matter. Our efforts were directed at pushing the limits of what was possible in terms of sensitivity to such weak interactions,” explained Lee.

The detector, which is shielded with advanced materials to minimize noise and interference, was designed to detect extremely rare events, including the interaction between dark matter particles and electrons. Over the course of 1.2 years, the team collected valuable data, refining their understanding of how LDM might interact with matter.

While the researchers did not detect any definitive signals from LDM particles, they were able to establish significant constraints on how strongly light dark matter can interact with electrons. For dark matter particles with a mass around 100 keV/c², the NEON team improved the previous constraints by a factor of 1,000. Moreover, for the first time, the study provided constraints on LDM particles with masses below this range, a major step forward in dark matter research.

“The results of this study are significant,” Lee said. “While we didn’t observe any direct signals of LDM interactions, we were able to place tighter constraints on the possible properties of these particles. This provides valuable insight into the nature of LDM and will inform future searches.”

New Frontiers in Dark Matter Research

The NEON collaboration’s work is not only groundbreaking because it pushes the envelope on LDM research, but also because it demonstrates the potential of reactor-based experiments in the search for dark matter. The ability to use a nuclear reactor as both a source of high-energy photons and a controlled testing environment opens up new possibilities for future experiments. While most dark matter detection efforts have focused on particle accelerators or cosmological surveys, reactor-based experiments like NEON offer a complementary approach that could reveal new insights.

“This experiment opens the door for new avenues of dark matter research,” said Lee. “We demonstrated that nuclear reactors provide an ideal environment for exploring interactions between light dark matter and ordinary matter, and this approach could serve as a useful complement to other experimental methods.”

Although the NEON team did not detect LDM interactions in this initial phase, their findings could help guide future experiments in the search for these particles. Their efforts have set new limits on the possible properties of LDM and have highlighted the importance of continuing to explore under-explored mass ranges.

Future Directions

The NEON collaboration is already planning for the next phase of their research. The team aims to further lower the energy threshold of their experiments to investigate even lighter dark matter candidates, which might interact even more weakly with matter. They are also exploring ways to improve the shielding and noise reduction capabilities of their detectors to enhance the reliability of their results.

“Our long-term goal is to gather more data, improve our detector’s sensitivity, and extend our search to even lighter dark matter particles,” Lee added. “By refining our techniques and integrating our results with those of other experiments worldwide, we hope to build a more comprehensive understanding of dark matter and its elusive components.”

The NEON collaboration’s work could soon inspire other experimental groups to adopt similar approaches in their searches for LDM. With continued innovation and a growing array of experimental tools at their disposal, scientists are getting closer to unraveling the mystery of dark matter and understanding its role in shaping the universe.

Conclusion

The recent efforts by the NEON collaboration represent a significant milestone in the ongoing search for light dark matter. Their innovative approach, combining the unique environment of a nuclear reactor with cutting-edge detection technology, has set new boundaries in the field. Although no direct signals were found, the team’s results provide crucial constraints on the properties of light dark matter and open up exciting new directions for future research.

As experiments continue and detection methods improve, the hope is that scientists will one day uncover the nature of this elusive form of matter, offering answers to some of the most fundamental questions about the universe and its composition. The work of the NEON collaboration represents a key step toward this goal, and their findings will likely play a crucial role in shaping the future of dark matter research.

Reference: J. J. Choi et al, First Direct Search for Light Dark Matter Using the NEON Experiment at a Nuclear Reactor, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.021802.