In the vast and often silent theater of the cosmos, stars live long lives—and sometimes, they die with drama. One such dramatic finale has now taken a compelling twist thanks to the unparalleled vision of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Scientists believed they had witnessed the first star in recorded history to swallow a planet whole, a cataclysmic end to a celestial relationship. But as it turns out, this wasn’t a sudden, fiery gulp from a swelling red giant as originally thought. Instead, what unfolded was a slow-motion demise: a planet spiraling inward, doomed to fall.

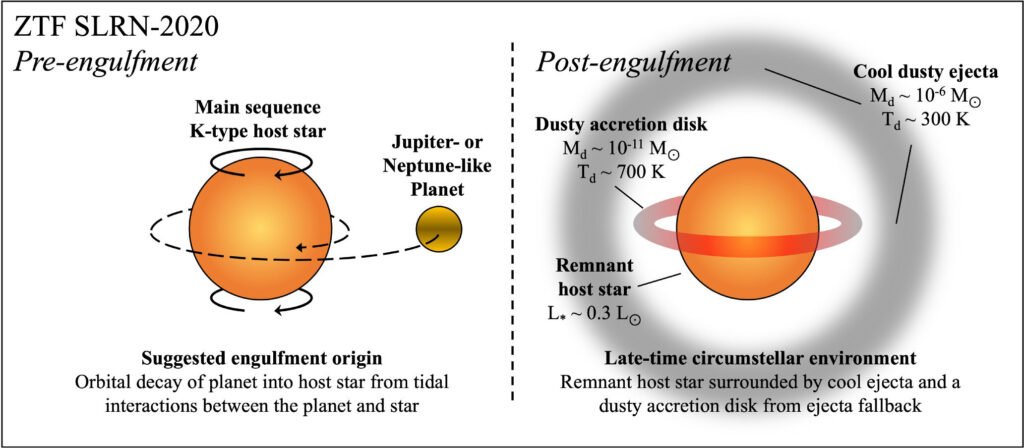

This surprising rewrite of a cosmic story was unveiled in a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, detailing a forensic investigation by JWST that paints a much more nuanced picture of planetary destruction. In place of a dramatic expansion, researchers found a silent betrayal: the planet’s orbit gradually decayed over millions of years, dragging it ever closer to the jaws of its host star—until, inevitably, it vanished within.

The Star That Bit Back: ZTF SLRN-2020

The star at the heart of this scene lies deep within the Milky Way, some 12,000 light-years away from Earth. It goes by the unassuming name ZTF SLRN-2020, identified during a sudden optical brightening observed by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) in 2020. From Earth, it looked like a flare-up, a bright burst of light in the sky that caught astronomers’ attention.

Yet even before this visible outburst, another cosmic whisper had already hinted something strange was happening. Infrared data from NASA’s NEOWISE spacecraft showed the star brightening nearly a year earlier. That discrepancy—infrared before optical—suggested the creation of a thick cloud of dust around the star. A dust-shrouded mystery was unfolding.

At first glance, it seemed like a textbook case: a sun-like star aging into a red giant, ballooning outward, and enveloping a close-orbiting gas giant planet. But Webb’s follow-up changed everything.

Enter Webb: Peering Into the Final Moments

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope wasn’t just the latest observer—it was the game-changer. Equipped with instruments like the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), JWST brought the kind of resolution and sensitivity astronomers have dreamed of for decades. Its mission: a deep dive into the aftermath of ZTF SLRN-2020’s flare-up.

What Webb found was not a star that had swelled to swallow, but one that remained relatively compact. This was no red giant. Using MIRI, scientists were able to detect subtle mid-infrared emissions with astonishing precision, cutting through the dense region of space around the star. What they discovered contradicted the original theory: the star hadn’t become luminous or large enough to engulf a planet through expansion alone.

Instead, the planet had taken a tragic, gravitationally choreographed route inward. It was orbital decay—not stellar swelling—that led to the fatal end.

The Death Spiral: Planetary Doom in Slow Motion

According to the new analysis, the doomed world was roughly the size of Jupiter, orbiting its star perilously close—closer than Mercury orbits our own Sun. Over time, tidal forces and gravitational interactions slowly drained the planet’s orbital energy. Its fate was sealed not in a moment of fury, but in the slow clutch of a death spiral.

“The planet eventually started to graze the star’s atmosphere,” explained Morgan MacLeod, astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “Then it was a runaway process—once it dipped in, there was no coming back.”

As the gas giant breached the star’s outer envelope, it triggered violent reactions. Material was blasted outward from the star’s surface in a final, desperate act. As this gas cooled, it condensed into dust, forming the very cloud that NEOWISE had detected a year before the optical brightening.

It was cosmic poetry in motion: a planet smeared across the face of its own sun.

Leftovers of a Cosmic Collision

In the chaotic aftermath, astronomers expected to find a cooler shell of dust expanding outward from the star—a planetary tombstone, if you will. But Webb revealed something more intriguing: not just a dust cloud, but a hot, rotating disk of gas close to the star’s surface.

This inner region, observed with Webb’s NIRSpec, showed spectral fingerprints of molecules like carbon monoxide. This wasn’t just the ghost of a planet—it was an active, turbulent structure, still very much shaped by the swallowed planet’s demise.

“With such a transformative telescope like Webb, it was hard for me to have any expectations of what we’d find,” said Colette Salyk, an exoplanet researcher at Vassar College and co-author of the study. “But I certainly didn’t expect to see what looked like the characteristics of a planet-forming region in the aftermath of a planetary engulfment.”

That paradox is tantalizing: something that looks like the birthplace of planets, but is in fact their grave.

What This Means for Our Solar System

For Earthlings gazing skyward, the study raises an uncomfortable question: could it happen here?

The short answer? Not anytime soon—but yes, one day.

Stars like our Sun are expected to swell into red giants billions of years from now. Mercury and Venus will almost certainly be consumed. Earth’s fate is less certain—our planet might escape, only to be scorched beyond habitability, or it might meet the same doom as the planet in ZTF SLRN-2020.

But the bigger picture is what really intrigues scientists. This study shows that planetary engulfment doesn’t require a star to evolve into a red giant. Close-in gas giants, like the infamous “hot Jupiters” found around many stars, may face their own destruction far earlier than previously thought, just from orbital decay.

In other words: the universe is not a static stage, and planetary systems do not live forever.

The Bigger Picture: A New Class of Events

ZTF SLRN-2020 is now the poster child of a new class of cosmic events—sudden, infrared-bright outbursts caused by dying planetary systems. These events had been spotted before, but without high-resolution follow-up, they remained ambiguous. Now, thanks to Webb, scientists can dissect them in detail.

“This is truly the precipice of studying these events,” said lead researcher Ryan Lau of NSF NOIRLab. “This is the only one we’ve observed in action, and it’s the best detection of the aftermath. We hope it’s just the start of our sample.”

These findings come from one of JWST’s “Target of Opportunity” programs—observations rapidly triggered in response to rare and unexpected events, like supernovae or gamma-ray bursts. ZTF SLRN-2020 was among the first such events Webb was tasked to study.

The Hunt Continues

Looking ahead, astronomers hope to catch more planetary engulfments in the act. The upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope are poised to play key roles. Both are designed to survey large areas of the sky repeatedly, looking for changes—stellar flickers, flashes, or infrared whispers—that signal something extraordinary has occurred.

Each new observation could offer fresh insight into the life cycles of stars and the fates of their planetary companions. And each one will continue to refine our understanding of how, when, and why stars consume their planets.

The cosmos, it seems, is full of slow-burn tragedies—of worlds spiraling inward, unseen until it’s too late.

Thanks to the eyes of Webb, we’re finally starting to see them clearly.

Reference: Ryan M. Lau et al, Revealing a Main-sequence Star that Consumed a Planet with JWST, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/adb429. iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/1538-4357/adb429