In the long saga of human history, few moments rival the impact of the Neolithic Revolution—the pivotal transformation from a world of wandering hunters and gatherers to one shaped by the tools of farming, animal domestication, and permanent settlement. For centuries, archaeologists and scientists have debated the catalyst for this seismic shift. Was it a brilliant human innovation? A slow cultural evolution? Or could something even more powerful have intervened?

Now, a groundbreaking study led by Professor Amos Frumkin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is turning conventional theories on their head. Published in the Journal of Soils and Sediments, this research argues that catastrophic natural forces, rather than human ingenuity alone, may have kickstarted agriculture as a survival response to a collapsing environment over 8,000 years ago. With forensic precision, the study reconstructs a landscape ravaged by fire, stripped of vegetation, and reimagined by necessity into the first fields of domesticated grain. And it all began in the southern Levant, the very cradle of civilization.

Beneath the Ashes: A Hidden Story in the Soil

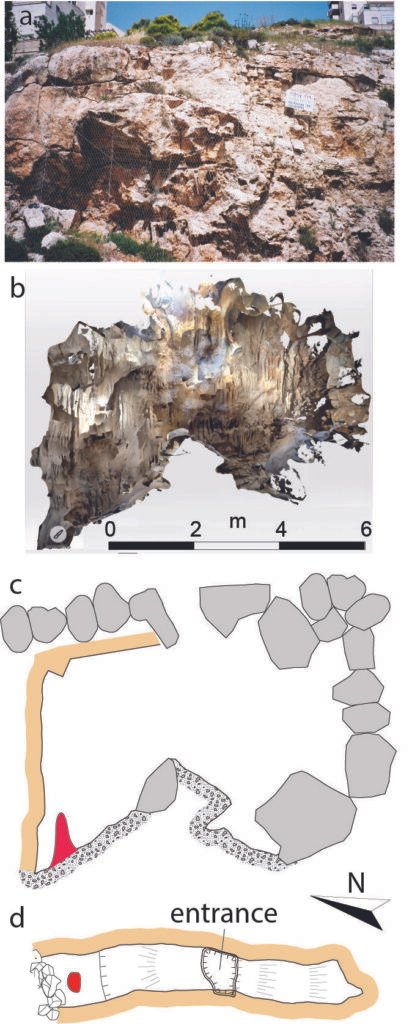

To unravel this ancient mystery, Frumkin and his team turned to the Earth itself. The clues lay buried not in stone tools or cave paintings, but in microscopic particles of charcoal, ancient cave formations, and the sediments of long-dried lakes. The region of focus—the southern Levant, encompassing parts of modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan—was a crossroads of early human settlement. It was here that some of the earliest known villages and farming practices emerged.

But as Frumkin dug deeper, what he uncovered was not a tale of smooth progress. Instead, the land told a story of trauma. High-resolution environmental records, meticulously analyzed, revealed a dramatic increase in wildfires during the early Holocene epoch, around 8.2 thousand years ago. This timing coincides with a well-known climatic disturbance known as the 8.2 kiloyear event, a sudden cooling episode that disrupted global weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere.

The evidence was not speculative. Charcoal fragments embedded in lakebeds told of vast fires, intense and widespread, that scorched the landscape. Speleothems—those slow-growing mineral formations inside caves—preserved geochemical fingerprints of changing soil conditions above. The levels of carbon and strontium isotopes in these formations traced a narrative of sudden erosion and vegetation loss, while fluctuations in Dead Sea water levels pointed to volatile precipitation and runoff patterns. All of this painted a picture not of peaceful evolution, but of a continent on fire.

When Lightning Struck: Climate as Catalyst

What could have caused such sweeping destruction? According to Frumkin’s analysis, the culprit was not human—but cosmic. The early Holocene was marked by a natural shift in the Earth’s orbital configuration, subtly altering solar radiation and changing the rhythms of the climate. These changes triggered dry thunderstorms—intense electrical storms with minimal rainfall—across the Levant.

Unlike typical thunderstorms that bring nourishing rain, these storms ignited flames without quenching them. Lightning bolts tore through dry forests and grasslands, igniting infernos that devoured ecosystems. Without consistent rainfall to stop them, these fires spread unchecked across the hills and plains, erasing plant life that had once stabilized the fragile soil.

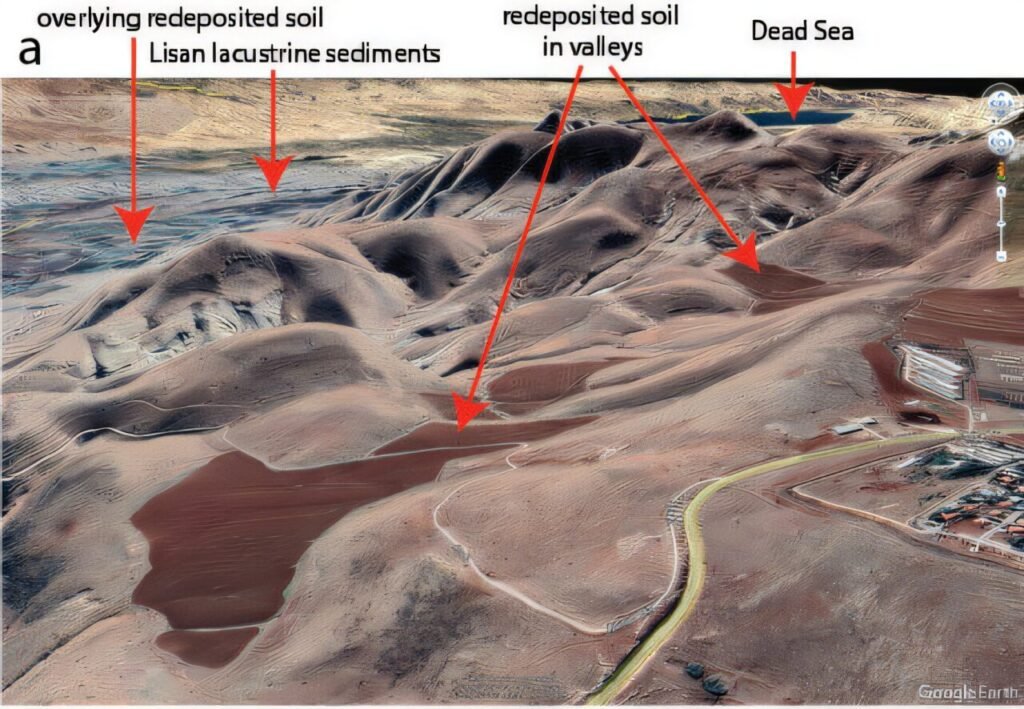

The aftermath was equally devastating. Bare hillsides, no longer anchored by vegetation, gave way to torrents of erosion. Rainfall, when it did come, sluiced away topsoil and carried it downhill, where it accumulated in low-lying valley basins. These valleys, once part of the wild hunting grounds of the Mesolithic, were transformed—suddenly blanketed by rich, reworked soils, unusually fertile and situated close to water sources.

What emerged, in Frumkin’s words, was an environmental tipping point. The landscape had shifted, and with it, so did the possibilities for human survival.

Necessity, Not Innovation: A Radical Reinterpretation

“This wasn’t a gradual cultural shift—it was a response to environmental collapse,” says Frumkin, challenging one of archaeology’s most sacred narratives. For decades, scholars have emphasized the Neolithic Revolution as a product of human curiosity and technological progress—a natural outgrowth of growing populations and sophisticated tool use.

But what if the first farmers weren’t inventors, but refugees? What if they turned to agriculture not out of curiosity, but desperation?

The study offers compelling support for this theory. As forests burned and game animals disappeared, traditional food sources would have become scarce. The formerly abundant landscapes that supported mobile hunter-gatherer bands were now hostile, broken, and unpredictable. Foraging was no longer sustainable. Settling down near water and fertile soil was no longer a choice—it was the only viable path to survival.

This theory also helps explain the sudden clustering of Neolithic settlements along certain corridors in the Levant, especially the Jordan Valley. These communities appeared not randomly, but over areas with thick, flood-borne soils derived from nearby eroded slopes. In these newly enriched valleys, wild cereals and legumes may have flourished without deliberate cultivation at first—natural gardens seeded by chaos. But once people began to recognize the bounty of these soils, the leap to planting, tending, and eventually domesticating crops was inevitable.

The Landscape that Shaped Humanity

Frumkin’s findings encourage a radical shift in how we view early human settlement—not as the result of some abstract enlightenment, but as a deeply grounded response to ecological upheaval. The evidence from caves, lakes, and soils forces us to confront how deeply climate and geology have always shaped human fate.

The pattern emerging from this study also fits a broader global theme. Across the world, many early agricultural societies appeared following periods of climatic disruption. In East Asia, the rise of rice farming followed monsoon variability. In the Andes, Andean farmers responded to glacial melt and seasonal instability. Could it be that climate shock, not innovation alone, is the true parent of agriculture?

If so, then the Neolithic Revolution was less of a smooth dawn and more of a firestorm—one that tore through old ways and gave birth to the new.

Rewriting the Origins of Civilization

The implications of this study go far beyond a single region. If natural wildfires and soil redistribution were key to humanity’s first sustained experiments in farming, we may need to rewrite much of what we know about how civilization began. The familiar images of ancient people slowly mastering seeds and tools may need to be reimagined against the backdrop of catastrophe—lightning, smoke, and scorched earth.

It also underscores the fragility and resilience of human societies in the face of climate change. The same forces that drove ancient people to domesticate crops are, in a sense, echoing back at us today. Extreme weather, soil degradation, and water scarcity are reshaping agriculture again in the modern era, albeit on a global scale.

Frumkin’s research invites us not just to marvel at the past, but to learn from it. “Environmental change is not new,” he notes. “But how societies respond determines their trajectory. The Neolithic Revolution wasn’t just a technical turning point—it was a human adaptation to chaos.”

Conclusion: A New Story from the Ashes

The story told by Professor Amos Frumkin and his team is one of both destruction and creation. It reveals how lightning storms and landslides, born from ancient orbital rhythms, helped sculpt the fertile valleys where humanity first began to cultivate crops. In doing so, it reclaims the Neolithic Revolution from the realm of myth and places it firmly in the natural world—an adaptation forged in fire, sown in soil, and rooted in the elemental forces of the Earth.

In the sediment layers of lakebeds and the mineral hearts of caves, a new narrative has emerged. It’s a story of survival, not supremacy; of firelight, not foresight. And it reminds us that behind every field of wheat lies a landscape that once burned.

Reference: Amos Frumkin, Catastrophic fires and soil degradation: possible association with the Neolithic revolution in the southern Levant, Journal of Soils and Sediments (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s11368-025-04021-x

Behind every word on this website is a team pouring heart and soul into bringing you real, unbiased science—without the backing of big corporations, without financial support.

When you share, you’re doing more than spreading knowledge.

You’re standing for truth in a world full of noise. You’re empowering discovery. You’re lifting up independent voices that refuse to be silenced.

If this story touched you, don’t keep it to yourself.

Share it. Because the truth matters. Because progress matters. Because together, we can make a difference.

Your share is more than just a click—it’s a way to help us keep going.