In the rich and varied tapestry of Britain’s Roman history, the discovery of the Thetford treasure remains one of the most significant finds, revealing not only the material wealth and artistry of the time but also providing new insights into the cultural and religious landscape of late Roman Britain. A recent paper published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology sheds fresh light on the nature of the treasure, its origins, and the religious practices of the period, suggesting that Thetford was a Pagan stronghold until the fifth century, challenging previous assumptions about the decline of Paganism in Roman Britain.

The Discovery of the Thetford Treasure

The Thetford treasure was unearthed in 1979 by a metal detectorist on a construction site at Fison’s Way on Gallows Hill in Thetford, East Anglia. What began as a chance discovery by a hobbyist became one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th century. The hoard contained 81 objects, including 22 gold finger-rings, a range of other gold jewelry, and 36 silver spoons or strainers. These objects were initially thought to date to the late fourth century, a time when Roman Britain was undergoing significant upheaval, with the withdrawal of Roman forces and the rise of new political and religious orders. However, a closer examination of the artifacts, as well as a re-evaluation of their historical context, has suggested that the hoard may have been buried much later, into the fifth century.

Today, the treasure is housed at the British Museum, where visitors can view the dazzling array of jewelry and utensils that give us a glimpse into the lives of Britain’s elite during the Roman period. Yet, it is the cultural and historical significance of the treasure that continues to captivate scholars and the public alike.

A Pagan Legacy into the Fifth Century

The new study, led by Professor Ellen Swift of the University of Kent, challenges long-held assumptions about the decline of Paganism in Roman Britain. Previous research suggested that Paganism in Britain largely waned in the late fourth century, particularly after the official adoption of Christianity as the state religion in the Roman Empire. The newly revised dating of the Thetford treasure, however, indicates that the Pagan religious practices associated with the hoard may have persisted into the early fifth century—decades longer than previously believed.

Swift argues that the evidence contained within the hoard provides compelling proof that a Pagan cult center existed in Thetford well into the fifth century. Her research highlights the religious context of the hoard, particularly focusing on the inscriptions found on several of the spoons within the treasure. These inscriptions, which had previously been interpreted as having a Pagan religious connection, now appear to confirm that the treasure was associated with religious practices that extended well beyond the traditional end date for Paganism in Roman Britain.

The evidence found at the Thetford site suggests that, contrary to previous assumptions, Paganism was not entirely supplanted by Christianity by the end of the fourth century. Instead, the findings indicate that a Pagan cult center in Thetford maintained its influence into the fifth century, serving as a focal point for religious activity during a time of great change and uncertainty in Britain.

The Wealth and Power Behind the Hoard

In addition to its religious significance, the wealth of the Thetford treasure points to the power and authority of its owner or the community that buried it. The hoard is not merely a collection of religious items; it is also a testament to the material wealth and economic prosperity of Thetford at the time. The variety and value of the objects in the hoard indicate that the community associated with it may have wielded considerable local power.

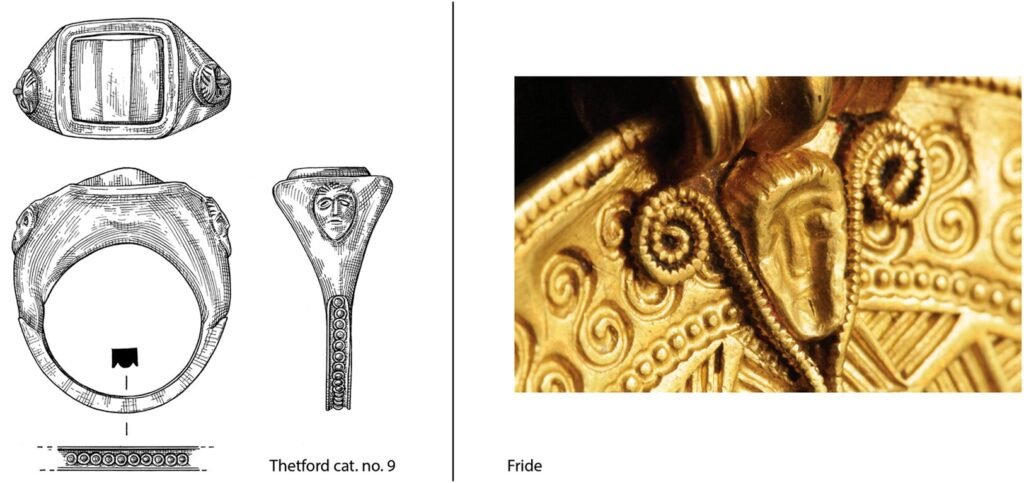

Among the items in the hoard, the gold finger-rings stand out as particularly intricate and valuable. These rings were not simply decorative; they served as markers of status and identity within the elite circles of Roman society. The spoons or strainers, often inscribed with religious symbols, further underscore the hoard’s connection to religious rites and the potential status of the person or group that buried it.

The wide array of items in the hoard suggests that Thetford was a place of significant economic and cultural activity, with access to luxury goods and trade networks that spanned the Roman Empire. This regional wealth, coupled with the religious significance of the hoard, paints a picture of a community that was both powerful and deeply engaged with the wider Roman world, even as it resisted the forces of change sweeping through Britain.

New Chronology: Fifth Century Re-Dating

Professor Swift’s new research, which re-dates the hoard to the fifth century, is supported by a detailed comparison of the objects found at Thetford with those from other, similarly dated archaeological contexts. The study draws parallels between the Thetford hoard and the Hoxne hoard, a significant find made in 1992 in Suffolk, which is now housed in the British Museum. The Hoxne hoard, which contains many of the same types of objects—such as silver spoons, jewelry, and other Roman artifacts—has been firmly dated to the early fifth century. The similarities between the two hoards suggest that Thetford’s treasure, too, was likely buried in the same period.

Swift’s re-dating of the Thetford hoard, based on these detailed comparisons, provides a new understanding of Britain’s relationship with the Roman world during the fifth century. The items in the hoard, with their varied origins and their stylistic connections to both Roman Britain and continental Europe, suggest that Britain was not as isolated as previously thought. Instead, the treasure reflects a continued engagement with the broader Mediterranean world during a period traditionally viewed as one of isolation and decline.

The Cultural Significance of the Jewelry

One of the most striking features of the Thetford hoard is the diversity of its jewelry, which offers valuable insights into the cultural exchanges that took place across the Roman Empire. The gold finger-rings, in particular, display a variety of styles that reflect different regional influences, suggesting that the jewelry was sourced from various parts of the empire.

Some of the latest-dating rings in the hoard appear to have originated in northern Italy or adjacent regions, while a necklace with conical beads is thought to have come from the Balkans. These pieces underscore the cosmopolitan nature of Roman Britain, where even remote provinces like Britain were connected to far-flung regions of the empire through trade and cultural exchange. The diverse origins of the jewelry in the Thetford hoard highlight the extent to which Roman elites shared a common material culture, with similar styles and forms appearing across the empire.

Moreover, the “Mediterranean Roman” style of much of the jewelry in the hoard reveals the spread of Roman cultural norms and aesthetics throughout the empire. This style, which was favored by the Roman elite, was not confined to Rome or Italy but was instead adopted by elites in regions as far apart as Britain, Spain, and the Balkans. The jewelry in the Thetford hoard thus serves as a testament to the interconnectedness of the Roman world and the shared cultural heritage of its elites.

A Wider European Context

The Thetford hoard also reinforces the idea that Britain, far from being a backwater at the edge of the Roman Empire, was an active participant in the imperial economy and culture. The items in the hoard show that Britain remained well connected to the wider Roman world, particularly through trade and diplomatic relationships. The diversity of the hoard’s contents suggests that Britain was part of a larger network of cultural and economic exchange that extended across the empire.

This new understanding of Britain’s relationship with the Roman world challenges the long-standing view of Britain as a peripheral province. Instead, the Thetford treasure reveals that Britain remained an integral part of the Roman Empire even into the fifth century, with elite communities in the province maintaining connections to the Mediterranean world long after the traditional end of Roman rule in Britain.

Conclusion: Rethinking the End of Roman Britain

The re-dating of the Thetford treasure to the fifth century offers a fresh perspective on the end of Roman Britain. Rather than a swift collapse of Pagan practices and Roman influence, the treasure suggests that Roman cultural and religious traditions persisted longer than previously believed. The Thetford hoard is not only a symbol of wealth and status but also a testament to the enduring cultural ties that connected Britain to the broader Roman world during a time of profound transition.

As scholars continue to investigate the Thetford treasure and other archaeological finds from the period, it is becoming increasingly clear that the story of Roman Britain is more complex and nuanced than once thought. The treasure’s rich cultural and religious significance continues to provide valuable insights into the diverse and interconnected world of late Roman Britain, challenging assumptions and offering new avenues for exploration and discovery.

Reference: Ellen Swift, Rethinking the date and interpretation of the Thetford treasure: a 5th-c. hoard of gold jewelry and silver spoons, Journal of Roman Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1017/S1047759424000278

Behind every word on this website is a team pouring heart and soul into bringing you real, unbiased science—without the backing of big corporations, without financial support.

When you share, you’re doing more than spreading knowledge.

You’re standing for truth in a world full of noise. You’re empowering discovery. You’re lifting up independent voices that refuse to be silenced.

If this story touched you, don’t keep it to yourself.

Share it. Because the truth matters. Because progress matters. Because together, we can make a difference.

Your share is more than just a click—it’s a way to help us keep going.