The enigma of how ancient Mars, with its now cold and dry landscape, once boasted flowing rivers, lakes, and possibly even conditions conducive to life has intrigued scientists for decades. Recent research by scientists at Harvard University’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) has shed new light on this mystery, offering a plausible explanation for how the Red Planet was able to maintain enough warmth to support water in its distant past. By exploring the intricate chemistry of Mars’ early atmosphere, researchers have found clues that reveal a unique mechanism capable of warming the planet and keeping it hydrated.

The Puzzle of Ancient Mars

Mars today is a starkly cold, dry, and desolate world. The planet lacks surface water in any significant amount, and its atmosphere is thin, with little capacity to sustain life as we know it. However, when scientists look at evidence from Martian rocks, valleys, and riverbeds, they see strong indications that liquid water was once abundant. There are geological features that suggest the presence of rivers, lakes, and possibly even a vast ocean billions of years ago, during Mars’ early history.

Given that Mars is farther from the Sun than Earth and the Sun was weaker during the early solar system, how was it possible for Mars to have been warm enough for liquid water to exist? The answer is crucial, not just for understanding Mars’ history, but for investigating the potential for life elsewhere in our solar system.

The Hydrogen-Hypothesis

Previous theories suggested that a greenhouse effect on ancient Mars could have provided the necessary warmth for liquid water. A combination of gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO₂), is thought to have contributed to this warming. However, a key ingredient in these greenhouse gas models was hydrogen—specifically hydrogen mixed with CO₂ to trigger episodes of intense greenhouse warming.

The problem with this theory lies in the lifetime of atmospheric hydrogen. Hydrogen is not a particularly stable molecule, and it would have dissipated from Mars’ atmosphere rather quickly, especially since the planet lacks a strong magnetic field to shield its atmosphere from solar winds. Without an ongoing replenishment mechanism for hydrogen, this theory alone could not account for the long-term warm spells observed in the Martian geological record.

A Deeper Dive into Chemistry

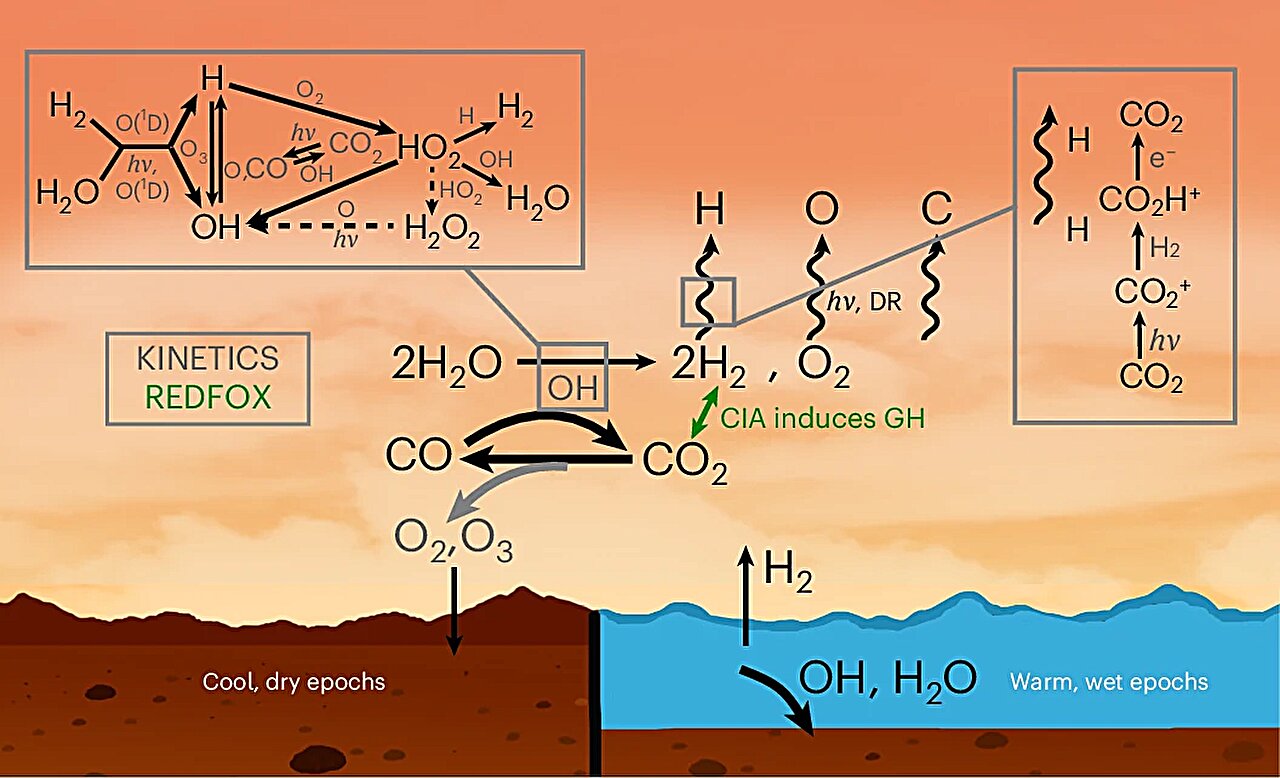

To refine the understanding of ancient Mars’ climate system, the Harvard team, led by Danica Adams and Robin Wordsworth, turned to advanced photochemical modeling to simulate the behavior of gases and how they reacted with each other and with Mars’ surface over time. Photochemistry refers to chemical reactions that occur under the influence of light—something already used extensively on Earth for tracking air pollution.

Wordsworth, the Gordon McKay Professor of Environmental Science and Engineering at SEAS, emphasized the importance of reconstructing early Mars in as much detail as possible. Their model focused on the planet’s atmosphere, allowing the team to explore the delicate interplay between gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide. Their approach enabled them to understand how these compounds fluctuated over millions of years and how these fluctuations may have contributed to Mars’ warming periods.

Adams and her team employed an enhanced model called KINETICS to study how the combination of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and other gases responded to the conditions of early Mars. The model considered the relationship between these gases and the Martian surface. Importantly, it looked at how they could have undergone chemical reactions that would trap warmth within the planet’s atmosphere over extended periods.

Mars’ Ancient Climate Cycle

The new modeling revealed that Mars underwent a series of episodic warm spells between approximately 4 to 3 billion years ago. During these periods, the planet’s climate would have experienced bursts of warmth lasting up to 100,000 years or more. The study suggests that these warming intervals occurred as a result of periodic fluctuations in the Martian atmosphere. Such warming events likely provided the necessary conditions for rivers, lakes, and other bodies of liquid water to form and persist.

One of the key findings was that during Mars’ Noachian and Hesperian periods—geological eras known for having hosted early life—Mars was not continuously warm, but instead experienced fluctuations between warm and cold phases. These alternations may have lasted for tens of millions of years. The findings align with surface features observed on Mars today, such as valleys and sedimentary deposits formed by flowing water.

Crucially, Adams’ team identified a fundamental link between crustal hydration—the process by which water is absorbed by the Martian surface—and the buildup of hydrogen in the planet’s atmosphere. Over millions of years, Mars’ surface would have released water vapor and other gases into the atmosphere during periods of warming, allowing hydrogen to accumulate. This buildup of hydrogen acted as a greenhouse gas, working in tandem with CO₂ to trigger further warming. During these warm intervals, the atmosphere became more conducive to sustaining water and potentially allowing life to emerge.

How the Martian Chemistry Changed Over Time

Mars’ atmosphere underwent dramatic changes in terms of chemical composition throughout its history. When Mars was warmer, sunlight would break apart carbon dioxide molecules into CO (carbon monoxide) and O₂ (oxygen). This reaction set off a chemical cycle where CO was eventually recycled back into CO₂, sustaining a greenhouse effect capable of keeping the planet warm enough to host liquid water.

However, when colder periods set in, the cycle slowed down and carbon monoxide (CO) began to accumulate. This accumulation of CO and the reduced activity of the warming cycle led Mars into a more oxidized state, making it more difficult for liquid water to persist. These fluctuations between cold and warm states caused substantial changes in the atmosphere’s redox states—the balance between oxidizing and reducing conditions. Understanding these changes provides a better picture of how prebiotic chemistry—the necessary building blocks for life—might have unfolded on Mars during these warmer episodes.

The fluctuations in temperature and atmospheric conditions helped establish a complex environmental scenario that offered time windows for the possibility of life to emerge—though only during specific warming periods. During the cold phases, any life that may have existed would have faced challenges such as freezing temperatures and a harsher, more chemically altered atmosphere.

Testing the Theory

The researchers anticipate that isotope chemical modeling—a method used to study the chemical composition of rocks—will soon offer a way to confirm their model. Mars exploration missions, particularly the forthcoming Mars Sample Return mission, which aims to bring back rock samples from Mars, could provide valuable data to test their predictions. By analyzing the isotopic fingerprints of Martian rocks, scientists could trace the detailed history of climate cycles, atmosphere composition, and changes in Mars’ surface over millions of years.

One of the key advantages of studying Mars is that the planet’s lack of plate tectonics has preserved its surface features for billions of years. Unlike Earth, where plate tectonics continually reshape the landscape, the Martian surface remains largely the same as it did long ago. This makes the surface an excellent “time capsule,” providing vital clues to the planet’s ancient climate and environmental changes.

The Bigger Picture: A Study of Planetary Evolution

For Adams and Wordsworth, this study of ancient Mars offers an exciting opportunity to better understand planetary evolution across our solar system and beyond. The cyclical processes of warming and cooling on Mars provide an important lesson on how planetary atmospheres can evolve over time, influenced by both chemical and physical factors. By synthesizing knowledge from atmospheric chemistry, climate science, and geology, researchers can start to better predict the evolution of distant worlds, possibly revealing those where conditions may be right for life—or life to emerge in the future.

As NASA and other space agencies continue to push the boundaries of interplanetary exploration, a comprehensive understanding of Mars’ past—how it could support water, and perhaps life—may provide us with more than just answers about Mars. It offers a broader view of the forces that shape planets throughout the universe, and how those processes may create habitable worlds.

With the promising potential of future missions, and the search for biomarkers on Mars and other planets, this groundbreaking research brings humanity one step closer to solving the mystery of whether life has ever existed beyond Earth.

Reference: Danica Adams et al, Episodic warm climates on early Mars primed by crustal hydration, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-024-01626-8